Woodrow Wilson: EIE-Ni (Normalizing subtype) [EIE-LII?]; or ESI/EII-Fi? or LII?

From Liberal Fascism by Jonah Goldberg; pages 104-20 [Ch. 3—“Woodrow Wilson and the Birth of Liberal Fascism” (HOW IT HAPPENED HERE)]:

The key concept for rationalizing progressive utopianism was “experimentation,” justified in the language of Nietzschean authenticity, Darwinian evolution, and Hegelian historicism and explained in the argot of William James’s pragmatism. Scientific knowledge advanced by trial and error. Human evolution advanced by trial and error. History, according to Hegel, progressed through the interplay of thesis and antithesis. These experiments were the same process on a vast scale. So what if Mussolini cracked skulls or Lenin lined up dissident socialists? The progressives believed they were participating in a process of ascendance to a more modern, more “evolved” way of organizing society, replete with modern machines, modern medicine, modern politics. In a distinctly American way, Wilson was as much a pioneer of this movement as Mussolini. A devoted Hegelian—he even invoked Hegel in a love letter to his wife—Wilson believed that history was a scientific, unfolding process. Darwinism was the perfect complement to such thinking because it seemed to confirm that the “laws” of history were reflected in our natural surroundings. “In our own day,” Wilson wrote while still a political scientist, “whenever we discuss the structure or development of a thing . . . we consciously or unconsciously follow Mr. Darwin.”

Wilson won the election of 1912 in an electoral college landslide, but with only 42 percent of the popular vote. He immediately set about to convert the Democratic Party into a progressive party and, in turn, make it the engine for a transformation of America. In January 1913 he vowed to “pick out progressives and only progressives” for his administration. “No one,” he proclaimed in his inaugural address, “can mistake the purpose for which the Nation now seeks to use the Democratic Party . . . I summon all honest men, all patriotic, all forward-looking men, to my side. I will not fail them, if they will but counsel and sustain me!” But he warned elsewhere, “If you are not a progressive . . . you better look out.” [It was around this time that the New Republic became akin to an intellectual PR firm for the Wilson administration. Teddy Roosevelt was so frustrated that his former cheering section had switched loyalties he proclaimed the New Republic a “negligible sheet run by two anemic Gentiles and two uncircumcised Jews.” Goldman, Rendezvous with Destiny, p. 194.]

Without the sorts of mandates or national emergencies other liberal presidents enjoyed, Wilson’s considerable legislative success is largely attributable to intense party discipline. In an unprecedented move, he kept Congress in continual session for a year and a half, something even Lincoln hadn’t done during the Civil War. Sounding every bit the Crolyite, he converted almost completely to the New Nationalism he had recently denounced, claiming he wanted no “antagonism between business and government.”* In terms of domestic policy, Wilson was successful in winning the support of progressives in all parties. But he failed to win over Roosevelt’s followers when it came to foreign policy. Despite imperialist excursions throughout the Americas, Wilson was deemed too soft. Senator Albert Beveridge, who had led the progressives to their greatest legislative successes in the Senate, denounced Wilson for refusing to send troops to defend American interests in China or install a strongman in Mexico. Increasingly, the core of the Progressive Party became almost entirely devoted to “preparedness”—shorthand for a big military buildup and imperial assertiveness.

The outbreak of war in Europe in 1914 distracted Wilson and the country from domestic concerns. It also proved a boon to the American economy, cutting off the flow of cheap immigrant labor and increasing the demand for American exports—something to keep in mind the next time someone tells you that the Wilson era proves progressive policies and prosperity go hand in hand.

*Woodrow Wilson, Address to a Joint Session of Congress on Trusts and Monopolies, Jan. 20, 1914, https://millercenter.org/the-preside...ess-trusts-and

Despite Wilson’s promise to keep us out of it, America entered the war in 1917. In hindsight, this was probably a misguided, albeit foregone, intervention. But the complaint that the war wasn’t in America’s interests misses the point. Wilson boasted as much time and again. “There is not a single selfish element, so far as I can see, in the cause we are fighting for,” he declared. Wilson was a humble servant of the Lord, and therefore selfishness could not enter into it.*

Even for ostensibly secular progressives the war served as a divine call to arms. They were desperate to get their hands on the levers of power and use the war to reshape society. The capital was so thick with would-be social engineers during the war that, as one writer observed, “the Cosmos Club was little better than a faculty meeting of all the universities.” [William E. Leuchtenburg, The FDR Years: On Roosevelt and His Legacy, p. 39.] Progressive businessmen were just as eager, opting to work for the president for next to nothing—hence the phrase “dollar-a-year men.” Of course, they were compensated in other ways, as we shall see.

*Wilson’s conviction that he was the messianic incarnation of world-historical forces was total. Time and again he argued that he was the instrument of God or history or both. He concluded a famous speech to the League to Enforce Peace:

“But I did not come here, let me repeat, to discuss a program. I came only to avow a creed and give expression to the confidence I feel that the world is even now upon the eve of a great consummation, when some common force will be brought into existence which shall safeguard right as the first and most fundamental interest of all peoples and all governments, when coercion shall be summoned not to the service of political ambition or selfish hostility, but to the service of a common order, a common justice, and a common peace. God grant that the dawn of that day of frank dealing and of settled peace, concord, and cooperation may be near at hand!”

Full text can be found at www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=65391 ; Woodrow Wilson, The Messages and Papers of Woodrow Wilson, vol. 1, ed. Albert Shaw, p. 275. See also “Text of the President’s Speech Discussing Peace and Our Part in a Future League to Prevent War,” New York Times, May 28, 1916, p. 1.

WILSON’S FASCIST POLICE STATE

Today we unreflectively associate fascism with militarism. But it should be remembered that fascism was militaristic because militarism was “progressive” at the beginning of the twentieth century. Across the intellectual landscape, technocrats and poets alike saw the military as the best model for organizing and mobilizing society. Mussolini’s “Battle of the Grains” and similar campaigns were publicized on both sides of the Atlantic as the enlightened application of James’s doctrine of the “moral equivalent of war.” There was a deep irony to America’s war aim to crush “Prussian militarism,” given that it was Prussian militarism which had inspired so many of the war’s American cheerleaders in the first place. The idea that war was the source of moral values had been pioneered by German intellectuals in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and the influence of these intellectuals on the American mind was enormous. When America entered the war in 1917, progressive intellectuals, versed in the same doctrines and philosophies popular on the European continent, leaped at the opportunity to remake society through the discipline of the sword.

It is true that some progressives thought World War I was not well-advised on the merits, and there were a few progressives—Robert La Follette, for example—who were decidedly opposed (though La Follette was no pacifist, having supported earlier progressive military adventures). But most supported the war enthusiastically, even fanatically (the same goes for a great many American Socialists). And even those who were ambivalent about the war in Europe were giddy about what John Dewey called the “social possibilities of war.” Dewey was the New Republic’s in-house philosopher during the lead-up to the war, and he ridiculed self-described pacifists who couldn’t recognize the “immense impetus to reorganization afforded by this war.” One group that did recognize the social possibilities of war were the early feminists who, in the words of Harriot Stanton Blatch, looked forward to new economic opportunities for women as “the usual, and happy, accompaniment of war.” Richard Ely, a fervent believer in “industrial armies,” was a zealous believer in the draft: “The moral effect of taking boys off street corners and out of saloons and drilling them is excellent, and the economic effects are likewise beneficial.” Wilson clearly saw things along the same lines. “I am an advocate of peace,” he began one typical declaration, “but there are some splendid things that come to a nation through the discipline of war.” ****** couldn’t have agreed more. As he told Joseph Goebbels, “The war . . . made possible for us the solution of a whole series of problems that could never have been solved in normal times.”*

We should not forget how the demands of war fed the arguments for socialism. Dewey was giddy that the war might force Americans “to give up much of our economic freedom . . . We shall have to lay by our good-natured individualism and march in step.” If the war went well, it would constrain “the individualistic tradition” and convince Americans of “the supremacy of public need over private possessions.” Another progressive put it more succinctly: “Laissez-faire is dead. Long live social control.” [McGerr, A Fierce Discontent, p. 282.]

*. . . for the Blatch quotation, see McGerr, Fierce Discontent, p. 282, and John M. Barry, The Great Influenza: The Epic Story of the Deadliest Plague in History, p. 127; for the Ely, see Murray N. Rothbard, “Richard T. Ely: Paladin of the Welfare-Warfare State,” Independent Review 6, no. 4 (Spring 2002), p. 587; for the Wilson, see “Gov. Wilson Stirs Spanish Veterans,” New York Times, Sept. 11, 1912, p. 3; for the ******, see The Goebbels Diaries, 1942-1943, ed. Louis P. Lochner, p. 314.

Croly’s New Republic was relentless in its push for war. In the magazine’s very first editorial, written by Croly, the editors expressed their hope that war “should bring with it a political and economic organization better able to redeem its obligations at home.” Two years later Croly again expressed his hope that America’s entry into the war would provide “the tonic of a serious moral adventure.” A week before America joined the war, Walter Lippmann (who would later write much of Wilson’s Fourteen Points) promised that hostilities would bring out a “transvaluation of values as radical as anything in the history of intellect.” This was a transparent invocation of Nietzsche’s call for overturning all traditional morality. Not coincidentally, Lippmann was a protégé of William James’s, and his call to use war to smash the old order illustrates how similar Nietzscheans and American pragmatists were in their conclusions and, often, their principles. Indeed, Lippmann was sounding the pragmatist’s trumpet when he declared that our understanding of such ideas as democracy, liberty, and equality would have to be rethought from their foundations “as fearlessly as religious dogmas were in the nineteenth century.”*

Meanwhile, socialist editors and journalists—including many from the Masses, the most audacious of the radical journals that Wilson tried to ban—rushed to get a paycheck from Wilson’s propaganda ministry. Artists such as Charles Dana Gibson, James Montgomery Flagg, and Joseph Pennell and writers like Booth Tarkington, Samuel Hopkins Adams, and Ernest Poole became cheerleaders for the war-hungry regime. Musicians, comedians, sculptors, ministers—and of course the movie industry—were all happily drafted to the cause, eager to wear the “invisible uniform of war.” Isadora Duncan, an avant-garde pioneer of what today would be called sexual liberation, became a toe tapper in patriotic pageants at the Metropolitan Opera House. The most enduring and iconic image of the time is Flagg’s “I Want You” poster of Uncle Sam pointing the shaming finger of the state-made-flesh at uncommitted citizens.

Almost alone among progressives, the brilliant, bizarre, disfigured genius Randolph Bourne seemed to understand precisely what was going on. The war revealed that a generation of young intellectuals, trained in pragmatic philosophy, were ill equipped to prevent means from becoming ends. The “peculiar congeniality between the war and these men” was simply baked into the cake, Bourne lamented. “It is,” he sadly concluded, “as if the war and they had been waiting for each other.” [Leuchtenburg, FDR Years, p. 39; David M. Kennedy, Over Here: The First World War and American Society, p. 52.]

Wilson the great centralizer and would-be leader of men moved overnight to empower these would-be social engineers, creating a vast array of wartime boards, commissions, and committees. Overseeing it all was the War Industries Board, or WIB, chaired by Bernard Baruch, which whipped, cajoled, and seduced American industry into the loving embrace of the state long before Mussolini or ****** contemplated their corporatist doctrines. The progressives running the WIB had no illusions about what they were up to. “It was an industrial dictatorship without parallel—a dictatorship by force of necessity and common consent which step by step at last encompassed the Nation and united it into a coordinated and mobile whole,” declared Grosvenor Clarkson, a member and subequent historian of the WIB. [Grosvenor Clarkson, Industrial America in the World War: The Strategy Behind the Line, 1917-1918, p. 292.]

More important than socializing industry was nationalizing the people for the war effort. “Woe be to the man or group of men that seeks to stand in our way,” Wilson threatened in June 1917. Harking back to his belief that “leaders of men” must manipulate the passions of the masses, he approved and supervised one of the first truly Orwellian propaganda efforts in Western history. He set the tone himself when he defended the first military draft since the Civil War. “It is in no sense a conscription of the unwilling: it is, rather, selection from a nation which has volunteered in mass.” [McGerr, Fierce Discontent, p. 289; Woodrow Wilson, A Proclamation by the President of the United States, as printed in New York Times, May 19, 1917, p. 1.]

A week after the war started, Walter Lippmann—no doubt eager to set about the work of unleashing a transvaluation of values—sent a memo to Wilson imploring him to commence with a sweeping propaganda effort. Lippmann, as he argued later, believed that most citizens were “mentally children or barbarians” and therefore needed to be directed by experts like himself. Individual liberty, while nice, needed to be subordinated to, among other things, “order.” [Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion]

Wilson tapped the progressive journalist George Creel to head the Committee on Public Information, or CPI, the West’s first modern ministry for propaganda. Creel was a former muckraking liberal journalist and police commissioner in Denver who had gone so far as to forbid his cops from carrying nightsticks or guns. He took to the propaganda portfolio immediately, determined to inflame the American public into “one white-hot mass” under the banner of “100 percent Americanism.” “It was a fight for the minds of men, for the ‘conquest of their convictions,’ and the battle line ran through every home in every country,” Creel recalled. Fear was a vital tool, he argued, “an important element to be bred into the civilian population. It is difficult to unite a people by talking only on the highest ethical plane. To fight for an ideal, perhaps, must be coupled with thoughts of self-preservation.” [McGerr, Fierce Discontent, p. 288; Barry, Great Influenza, p. 127.]

Countless other liberal and leftist intellectuals lent their talents and energies to the propaganda effort. Edward Bernays, who would be credited with creating the field of public relations, cut his teeth on the Creel Committee, learning the art of “the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses.” The CPI printed millions of posters, buttons, pamphlets, and the like in eleven languages not counting English. The committee eventually had more than twenty subdivisions with offices in America and around the world. The Division of News alone issues more than six thousand releases. Just under one hundred pamphlets were printed with an estimated circulation of seventy-five million. A typical poster for Liberty Bonds cautioned, “I am Public Opinion. All men fear me! . . . [I]f you have the money to buy and do not buy, I will make this No Man’s Land for you!” A CPI poster asked, “Have you met the Kaiserite? . . . You find him in hotel lobbies, smoking compartments, clubs, offices, even homes . . . He is a scandalmonger of the most dangerous type. He repeats all the rumors, criticism, he hears about our country’s part in the war. He’s very plausible . . . People like that . . . through their vanity or curiosity or treason they are helping German propagandists sow the seeds of discontent.” [For the Bernays quotation, see Michael Kazin, The Populist Persuasion: An American History, p. 70. For the CPI posters, see Barry, Great Influenza, p. 127.]

One of Creel’s greatest ideas—an instance of “viral marketing” before its time—was the creation of an army of nearly a hundred thousand “Four Minute Men.” Each was equipped and trained by the CPI to deliver a four-minute speech at town meetings, in restaurants, in theaters—anyplace they could get an audience—to spread the word that the “very future of democracy” was at stake. In 1917-18 alone, some 7,555,190 speeches were delivered in fifty-two hundred communities. These speeches celebrated Wilson as a larger-than-life leader and the Germans as less-than-human Huns. Invariably, the horrors of German war crimes expanded as the Four Minute Men plied their trade. The CPI released a string of propaganda films with such titles as The Kaiser, The Beast of Berlin, and The Prussian Cur. The schools, of course, were drenched in nationalist propaganda. Secondary schools and colleges quickly added “war studies courses” to the curriculum. And always and everywhere the progressives questioned the patriotism of anybody who didn’t act “100 percent American.”

Another Wilson appointee, the socialist muckraker Arthur Bullard—a former writer for the radical journal the Masses and an acquaintance of Lenin’s—was also convinced that the state must whip the people up into a patriotic fervor if America was to achieve the “transvaluation” the progressives craved. In 1917 he published Mobilising America, in which he argued that the state must “electrify public opinion” because “the effectiveness of our warfare will depend on the ardour we throw into it.” Any citizen who did not put the needs of the state ahead of his own was merely “dead weight.” Bullard’s ideas were eerily similar to the Sorelian doctrines of the “vital lie.” “Truth and falsehood are arbitrary terms . . . there are lifeless truths and vital lies . . . The force of an idea lies in its inspirational value. It matters very little if it’s true or false.” [Barry, Great Influenza, p. 126.]

*For the Croly quotations, see “The End of American Isolation,” editorial, New Republic, Nov. 7, 1914, quoted in John B. Judis, “Homeward Bound,” New Republic, March 3, 2003, p. 16; and Ekirch, Decline of American Liberalism, p. 202. For the Lippman quotations, see Ronald Steel, “The Missionary,” New York Review of Books, Nov. 20, 2003; and Heinz Eulau, “From Public Opinion to Public Philosophy: Walter Lippmann’s Classic Reexamined,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology, vol. 15, no. 4 (July 1956), p. 441.

The radical lawyer and supposed civil libertarian Clarence Darrow—today a hero to the left for his defense of evolution in the Scopes “Monkey” trial—both stumped for the CPI and defended the government’s censorship efforts. “When I hear a man advising the American people to state the terms of peace,” Darrow wrote in a government-backed book, “I know he is working for Germany.” In a speech at Madison Square Garden he said that Wilson would have been a traitor not to defy Germany, and added, “Any man who refuses to back the President in this crisis is worse than a traitor.” Darrow’s expert legal opinion, it may surprise modern liberals to know, was that once Congress had decided on war, the right to question that decision evaporated entirely (an interesting standard given the tendency of many to assert that the Bush administration has behaved without precedent in its comparatively tepid criticism of dissent). Once the bullets fly, citizens lose the right even to discuss the issue, publicly or privately; “acquiescence on the part of the citizen becomes a duty.”* (It’s ironic that the ACLU made its name supporting Darrow at the Scopes trial.)

* “Charges Traitors in America Are Disrupting Russia,” New York Times, Sept. 16, 1917, p. 3; Stephen Vaughn, “First Amendment Liberties and the Committee on Public Information,” American Journal of Legal History 23, no. 2 (April 1979), p. 116.

The rationing and price-fixing of the “economic dictatorship” required Americans to make great sacrifices, including the various “meatless” and “wheatless” days common to all of the industrialized war economies in the first half of the twentieth century. But the tactics used to impose those sacrifices dramatically advanced the science of totalitarian propaganda. Americans were deluged with patriotic volunteers knocking on their doors to sign this pledge or that oath not only to be patriotic but to abstain from this or that “luxury.” Herbert Hoover, the head of the national Food Administration, made his reputation as a public servant in the battle to get Americans to tighten their belts, dispatching over half a million door knockers for his efforts alone. No one could dispute his gusto for the job. “Supper,” he complained, “is one of the worst pieces of extravagance that we have in this country.” [McGerr, Fierce Discontent, p. 293.]

Children were a special concern of the government’s, as is always the case in totalitarian systems. They were asked to sign a pledge card, “A Little American’s Promise”:

At table I’ll not leave a scrap

Of food upon my plate.

And I’ll not eat between meals but

For supper time I’ll wait.

I make that promise that I’ll do

My honest, earnest part

In helping my America

With all my loyal heart.

For toddlers who couldn’t sign a pledge card, let alone read, the Progressive war planners offered a rewritten nursery rhyme:

Little Boy Blue, come blow your horn!

The cook’s using wheat where she ought to use corn

And terrible famine our country will sweep,

If the cooks and the housewives remain fast asleep!

Go wake them! Go wake them! It’s now up to you!

Be a loyal American, Little Boy Blue! [Ibid., p. 293, 294.]

Even as the government was churning out propaganda, it was silencing dissent. Wilson’s Sedition Act banned “uttering, printing, writing, or publishing any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the United States government or the military.” The postmaster general was given the authority to deny mailing privileges to any publication he saw fit—effectively shutting it down. At least seventy-five periodicals were banned. Foreign publications were not allowed unless their content was first translated and approved by censors. Journalists also faced the very real threat of being jailed or having their supply of newsprint terminated by the War Industries Board. “Unacceptable” articles included any discussion—no matter how high-minded or patriotic—that disparaged the draft. “There is a limit,” Postmaster General Albert Sidney Burleson declared. That limit has been exceeded, he explained, when a publication “begins to say that this Government got in the war wrong, that it is in it for the wrong purposes, or anything that will impugn the motives of the Government for going into the war. They can not say that this Government is the tool of Wall Street or the munitions-makers . . . There can be no campaign against conscription and the Draft Law.”*

The most famous episode of censorship came with the government’s relentless campaign against the Masses, the radical literary journal edited by Max Eastman. The postmaster general revoked the magazine’s right to be distributed via the mails under the Espionage Act. Specifically, the government charged the magazine with trying to hamper military recruitment. Among the “illegal” contents: a cartoon proclaiming this was a war to make the world “safe for capitalism” and an editorial by Eastman praising the courage of draft resisters. Six editors faced trial in New York but managed to “win” hung juries (jurors and lawyers commented afterward that the defendants would almost certainly have been found guilty if any of them had been German or Jewish).

Of course, the “chilling effect” on the press in general was far more useful than the closures. Many of the journals that were shut down had tiny readerships. But the threat of being put out of business did wonders in focusing the minds of other editors. If the power of example wasn’t strong enough, editors received a threatening letter. If that didn’t work, they could lose their mail privileges “temporarily.” Over four hundred publications had been denied privileges by May 1918. The Nation had been suppressed for criticizing Samuel Gompers. The journal Public had been smacked for suggesting that the war should be paid for by taxes rather than loans, and the Freeman’s Journal and Catholic Register for reprinting Thomas Jefferson’s views that Ireland should be a republic. Even the pro-war New Republic wasn’t safe. It was twice warned that it would be banned from the mails if it continued to run the National Civil Liberties Bureau’s ads asking for donations and volunteers.

*H. W. Brands, The Strange Death of American Liberalism, p. 40. In all of the cases of Burleson’s clamping down on the press, there are only two instances when Wilson disagreed with his postmaster enough to redress the situation. In all the others Wilson steadfastly supported the government’s largely unlimited right to censor the press—including one instance when Burleson used his powers to harass a local Texas journal that criticized his decision to evict sharecroppers from his property. In a letter to one congressman, Wilson declared that censorship is “absolutely necessary to the public safety.” John Sayer, “Art and Politics, Dissent and Repression: The Masses Magazine Versus the Government, 1917-1918,” American Journal of Legal History 32, no. 1 (Jan. 1988), p. 46.

Then there was the inevitable progressive crackdown on individual civil liberties. Today’s liberals tend to complain about the McCarthy period as if it were the darkest moment in American history after slavery. It’s true: under McCarthyism a few Hollywood writers who’d supported Stalin and then lied about it lost their jobs in the 1950s. Others were unfairly intimidated. But nothing that happened under the mad reign of Joe McCarthy remotely compares with what Wilson and his fellow progressives foisted on America. Under the Espionage Act of June 1917 and the Sedition Act of May 1918, any criticism of the government, even in your own home, could earn you a prison sentence (a law Oliver Wendell Holmes upheld years after the war, arguing that such speech could be banned if it posed a “clear and present danger”). In Wisconsin a state official got two and a half years for criticizing a Red Cross fund-raising drive. A Hollywood producer received a ten-year stint in jail for making a film that depicted British troops committing atrocities during the American Revolution. One man was brought to trial for explaining in his own home why he didn’t want to buy Liberty Bonds. [Sayer, “Art and Politics, Dissent and Repression,” p. 64 n. 99; Ekirch, Decline of American Liberalism, pp. 216-17.]

No police state deserves the name without an ample supply of police. The Department of Justice arrested tens of thousands without just cause. The Wilson administration issued a letter for U.S. attorneys and marshals saying, “No German enemy in this country, who has not hitherto been implicated in plots against the interests of the United States, need have any fear of action by the Department of Justice so long as he observes the following warning: Obey the law; keep your mouth shut.” [Carl Brent Swisher, “Civil Liberties in War Time,” Political Science Quarterly 55, no. 3 (Sept. 1940), p. 335.] This blunt language might be forgivable except for the government’s dismayingly broad definition of what defined a “German enemy.”

The Justice Department created its own quasi-official fascisti, known as the American Protective League, or APL. They were given badges—many of which read “Secret Service”—and charged with keeping an eye on their neighbors, co-workers, and friends. Used as private eyes by overzealous prosecutors in thousands of cases, they were furnished with ample government resources. The APL had an intelligence division, in which members were bound by oath not to reveal they were secret policemen. Members of the APL read their neighbors’ mail and listened in on their phones with government approval. In Rockford, Illinois, the army asked the APL to help extract confessions from black soldiers accused of assaulting white women. The APL’s American Vigilante Patrol cracked down on “seditious street oratory.” One of its most important functions was to serve as head crackers against 'slackers' who avoided conscription. In New York City, in September 1918, the APL launched its biggest slacker raid, rounding up fifty thousand men. Two-thirds were later found to be innocent of all charges. Nevertheless, the Justice Department approved. The assistant attorney general noted, with great satisfaction, that America had never been more effectively policed. In 1917 the APL had branches in nearly six hundred cities and towns with a membership approaching a hundred thousand. By the following year, it had exceeded a quarter of a million. [See Howard Zinn, The Twentieth Century: A People’s History (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), pp. 89-92.]

One of the only things the layman still remembers about this period is a vague sense that something bad called the Palmer Raids occurred—a series of unconstitutional crackdowns, approved by Wilson, of 'subversive' groups and individuals. What is usually ignored is that the raids were immensely popular, particularly with the middle-class base of the Democratic Party. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer was a canny progressive who defeated the Republican machine in Pennsylvania by forming a tight bond with labor. He had hoped to ride the popularity of the raids straight into the Oval Office, and might have succeeded had he not been sidelined by a heart attack.

It's also necessary to note that the American Legion was born under inauspicious circumstances during the hysteria of World War I in 1919. Although it is today a fine organization with a proud history, one cannot ignore the fact that it was founded as an essentially fascist organization. In 1923 the national commander of the legion declared, “If ever needed, the American Legion stands ready to protect our country's institutions and ideals as the fascisti dealt with the destructionists who menaced Italy.”* FDR would later try to use the legion as a newfangled American Protective League to spy on domestic dissidents and harass potential foreign agents.

Vigilantism was often encouraged and rarely dissuaded under Wilson's 100 percent Americanism. How could it be otherwise, given Wilson's own warnings about the enemy within? In 1915, in his third annual message to Congress, he declared, “The gravest threats against our national peace and safety have been uttered within our own borders. There are citizens of the United States, I blush to admit, born under other flags . . . who have poured the poison of disloyalty into the very arteries of our national life; who have sought to bring the authority and good name of our Government into contempt, to destroy our industries wherever they thought it effective for their vindictive purposes to strike at them, and to debase our politics to the uses of foreign intrigue.” Four years later the president was still convinced that perhaps America's greatest threat came from “hyphenated” Americans. “I cannot say too often—any man who carries a hyphen about with him carries a dagger that he is ready to plunge into the vitals of this Republic whenever he gets ready. If I can catch any man with a hyphen in this great contest I will know that I have got an enemy of the Republic.”**

*Norman Hapgood, Professional Patriots, p. 62. See also John Patrick Diggins, Mussolini and Fascism: The View from America, p. 206. About a decade later, a legion representative from Texas pinned a legion button on Mussolini’s lapel, making him an honorary member. In return, Mussolini posed for a photograph wearing a Texas cowboy hat with the legion colonel.

This was the America Woodrow Wilson and his allies sought. And they got what they wanted. In 1919, at a Victory Loan pageant, a man refused to stand for the national anthem. When 'The Star-Spangled Banner' ended, a furious sailor shot the 'disloyal' man three times in the back. When the man fell, the Washington Post reported, 'the crowd burst into cheering and handclapping.' Another man who refused to rise for the national anthem at a baseball game was beaten by the fans in the bleachers. In February 1919 a jury in Hammond, Indiana, took two minutes to acquit a man who had murdered an immigrant for yelling, 'To Hell with the United States.' In 1920 a salesman at a clothing store in Waterbury, Connecticut, received a six-month prison sentence for referring to Lenin as 'one of the brainiest' leaders in the world. Mrs. Rose Pastor Stokes was arrested, tried, and convicted for telling a women's group, ‘I am for the people, and the government is for the profiteers.’ The Republican antiwar progressive Robert La Follette spent a year fighting an effort to have him expelled from the Senate for disloyalty because he'd given a Speech opposing the war to the Non-Partisan League. The Providence Journal carried a banner—every day!—warning readers that any German or Austrian ‘unless known by years of association should be treated as a spy.’ The Illinois Bar Association ruled that members who defended draft resisters were not only 'unprofessional' but 'unpatriotic.' [“President Greets Fliers,” Washington Post, Sept. 10, 1924; Ekirch, Decline of American Liberalism, p. 217; Barry, Great Influenza, p. 125.]

** “Congress Cheers as Wilson Urges Curb on Plotters,” New York Times, Dec. 8, 1915, p. 1; Charles Seymour, Woodrow Wilson and the World War: A Chronicle of Our Own Times, p. 79; “Suggests Canada Might Vote with US,” New York Times, Sept. 26, 1919, p. 3.

German authors were purged from libraries, families of German extraction were harassed and taunted, sauerkraut became ‘liberty cabbage,’ and—as Sinclair Lewis half-jokingly recalled—there was talk of renaming German measles ‘liberty measles.’ Socialists and other leftists who agitated against the war were brutalized. Mobs in Arizona packed Wobblies in cattle cars and left them in the desert without food or water. In Oklahoma, opponents of the war were tarred and feathered, and a crippled leader of the Industrial Workers of the World was hung from a railway trestle. At Columbia University the president, Nicholas Murray Butler, fired three professors for criticizing the war, on the grounds that ‘what had been wrongheadedness was now sedition. What had been folly was now treason.’ Richard Ely, enthroned at the University of Wisconsin, organized professors and others to crush internal dissent via the Wisconsin Loyalty Legion. Anybody who offered “opinions which hinder us in this awful struggle,” he explained, should be “fired” if not indeed “shot.” Chief on his list was Robert La Follette, whom Ely attempted to hound from Wisconsin politics as a “traitor” who “has been of more help to the Kaiser than a quarter of a million troops.”*

Hard numbers are difficult to come by, but it has been estimated that some 175,000 Americans were arrested for failing to demonstrate their patriotism in one way or another. All were punished, many went to jail.

For the most part, the progressives looked upon what they had created and said, “This is good.” The “great European war . . . is striking down individualism and building up collectivism,” rejoiced the Progressive financier and J. P. Morgan partner George Perkins. Grosvenor Clarkson saw things similarly. The war effort “is a story of the conversion of a hundred million combatively individualistic people into a vast cooperative effort in which the good of the unit was sacrificed to the good of the whole.” The regimentation of society, the social worker Felix Adler believed, was bringing us closer to creating the “perfect man . . . a fairer and more beautiful and more righteous type than any . . . that has yet existed.” The Washington Post was more modest. “In spite of excesses such as lynching,” it editorialized, “it is a healthful and wholesome awakening in the interior of the country.” [McGerr, Fierce Discontent, p. 299; “Stamping Out Treason,” editorial, Washington Post, April 12, 1918.]

Perhaps some added context is in order. At pretty much the exact moment when John Dewey, Herbert Croly, Walter Lippmann, and so many others were gushing about the “moral tonic” the war would provide and how it was the highest, best cause for all people dedicated to liberal, progressive values, Benito Mussolini was making nearly identical arguments. Mussolini had been the brains of the Italian Socialist Party. He was influenced by many of the same thinkers as the American progressives—Marx, Nietzsche, Hegel, James, and others—and he wanted Italy to fight on the Allied side, that is, the eventual American side. And yet Mussolini’s support for the war automatically rendered him and his Fascist movement “objectively” right-wing according to communist propaganda.

So does this mean that the editors of the New Republic, the progressives in Wilson’s government, John Dewey, and the vast majority of self-described American Socialists were all suddenly right-wingers? Of course not. Only in Italy—home of the most radical socialist party in Europe after Russia—did support for the war automatically transform left-wingers into right-wingers. In Germany the socialists in the Reichstag voted in favor of the war. In Britain the socialists voted in favor of the war. In America the socialists and progressives voted in favor of the war. This didn’t make them right-wingers; it made them shockingly bloodthirsty and jingoistic left-wingers. This is just one attribute of the progressives that has been airbrushed from popular history. “Perhaps I was as much opposed to the war as anyone in the nation,” declared none other than Mother Jones, a champion of “Americanist” socialism, “but when we get into a fight I am one of those who intend to clean hell out of the other fellow, and we have to clean the kaiser up . . . the grafter, the thief, the murderer.” She was hardly alone. The pro-war socialist Charles E. Russell declared that his former colleagues should be “driven from the country.” Another insisted that antiwar socialists should be “shot at once without an hour’s delay.” [Kazin, Populist Persuasion, p. 69; John Patrick Diggins, The Rise and Fall of the American Left, p. 102.]

In the liberal telling of America’s story, there are only two perpetrators of official misdeeds: conservatives and “America” writ large. Progressives, or modern liberals, are never bigots or tyrants, but conservatives often are. For example, one will virtually never hear that the Palmer Raids, Prohibition, or American eugenics were thoroughly progressive phenomena. These are sins America itself must atone for. Meanwhile, real or alleged “conservative” misdeeds—say, McCarthyism—are always the exclusive fault of conservatives and a sign of the policies they would repeat if given power. The only culpable mistake that liberals make is failing to fight “hard enough” for their principles. Liberals are never responsible for historic misdeeds, because they feel no compulsion to defend the inherent goodness of America. Conservatives, meanwhile, not only take the blame for events not of their own making that they often worked the most assiduously against, but find themselves defending liberal misdeeds in order to defend America herself.

War socialism under Wilson was an entirely progressive project, and long after the war it remained the liberal ideal. To this day liberals instinctively and automatically see war as an excuse to expand governmental control of vast swaths of the economy. If we are to believe that “classic” fascism is first and foremost the elevation of martial values and the militarization of government and society under the banner of nationalism, it is very difficult to understand why the Progressive Era was not also the Fascist Era.

Indeed, it is very difficult not to notice how the progressives fit the objective criteria for a fascist movement set forth by so many students of the field. Progressivism was largely a middle-class movement equally opposed to runaway capitalism above and Marxist radicalism below. Progressives hoped to find a middle course between the two, what the fascists called the “Third Way” or what Richard Ely, mentor to both Wilson and Roosevelt, called the “golden mean” between laissez-faire individualism and Marxist socialism. Their chief desire was to impose a unifying, totalitarian moral order that regulated the individual inside his home and out. The progressives also shared with the fascists and Nazis a burning desire to transcend class differences within the national community and create a new order. George Creel declared this aim succinctly: “No dividing line between the rich and poor, and no class distinctions to breed mean envies.” [McGerr, Fierce Discontent, p. 290.]

This was precisely the social mission and appeal of fascism and Nazism. In speech after speech, ****** made it clear that his goal was to have no dividing lines between rich and poor. “What a difference compared with a certain other country,” he declared, referring to war-torn Spain. “There it is class against class, brother against brother. We have chosen the other route: rather than to wrench you apart, we have brought you together.” Robert Ley, the head of the Nazis’ German Labor Front, proclaimed flatly, “We are the first country in Europe to overcome the class struggle.” Whether the rhetoric matched the reality is beside the point; the appeal of such a goal was profound and the intent sincere. A young and ambitious German lawyer who wanted to study abroad was persuaded by his friends to stay home so he wouldn’t miss the excitement. “The [Nazi] party was intending to change the whole concept of labour relations, based on the principle of co-determination and shared responsibility between management and workers. I knew it was Utopian but I believed in it with all my heart . . . ******’s promises of a caring but disciplined socialism fell on very receptive ears.”*

Of course, such utopian dreams would have to come at the price of personal liberty. But progressives and fascists alike were glad to pay it. “Individualism,” proclaimed Lyman Abbott, the editor of the Outlook, “is the characteristic of simple barbarism, not of republican civilization.” [McGerr, Fierce Discontent, p. 59.] The Wilsonian-Crolyite progressive conception of the individual’s role in society would and should strike any fair-minded person of any true liberal sensibility today as at least disturbing and somewhat fascistic. Wilson, Croly, and the vast bulk of progressives would have no principled objection to the Nazi conception of the Volksgemeinschaft—“people’s community,” or national community—or to the Nazi slogan about placing “the common good before the private good.” Progressives and fascists alike were explicitly indebted to Darwinism, Hegelianism, and Pragmatism to justify their worldviews. Indeed, perhaps the greatest irony is that according to most of the criteria we use to locate people and policies on the ideological spectrum in the American context—social bases, demographics, economic policies, social welfare provisions—Adolf ****** was indisputably to Wilson’s left.

This is the elephant in the corner that the American left has never been able to admit, explain, or comprehend. Their inability and/or refusal to deal squarely with this fact has distorted our understanding of our politics, our history, and ourselves. Liberals keep saying “it can’t happen here” with a clever wink or an ironic smile to insinuate that the right is constantly plotting fascist schemes. Meanwhile, hiding in plain sight is this simple fact: it did happen here, and it might very well happen again. To see the threat, however, you must look over your left shoulder, not your right.

*David Schoenbaum, ******’s Social Revolution: Class and Status in Nazi Germany, 1933-1939, p. 63; Michael Mann, Fascists, p. 146.

From Wilson’s War: How Woodrow Wilson’s Great Blunder Led to ******, Lenin, Stalin, and World War II by Jim Powell; pages 1-7 (Introduction: Arrogance and Power):

Wilson’s fateful decision was for the United States to enter World War I. This had horrifying consequences.

First, American entry enabled the Allies—principally Britain and France—to win a decisive victory and dictate harsh surrender terms on the losers, principally Germany.

Until the United States entered the war, which had begun in August 1914, it was stalemated. The British and French together always had more soldiers on the Western Front than the Germans, but the Germans had smarter generals and more guns. The British navy maintained a blockade that prevented the Germans from importing just about anything, including food, and the Germans had no way to invade England. Both sides suffered millions of fatalities, and their fighting forces were weary. Neither side had the capacity to dictate harsh terms to the other.

After two years of war, there was increasing support for peace on both sides. In Russia, as early as the summer of 1915, there were widespread protests against the war. Wilson repeatedly offered his services as a mediator for peace, but as historian Barbara Tuchman noted, “The talk exasperated the Allies. It was not mediation they wanted from America but her great, untapped strength.” In December 1916, the Germans proposed peace talks, but they wanted to retain the French and Belgian territory they occupied, and the idea was rejected; the British and French anticipated that the United States would enter the war and enable them to win a decisive victory that would avoid compromise with the Germans. Politicians on both sides knew they would be toppled if they couldn’t brag about territorial gains and if it became obvious that millions of people had died for nothing. In February 1917, the Hapsburg emperor Karl I pursued peace negotiations with the British and French, aimed at getting Austria-Hungary out of the war even if their ally Germany continued fighting, but Italy objected. If the United States had stayed out, the British and French would have been under more pressure to compromise. There probably would have been a negotiated settlement.

American entry in the war undermined efforts to develop a viable German republic. German generals Paul von Hindenburg and Erich von Ludendorff, who controlled the military and the government, recognized that the individual who carried out the surrender—by signing the armistice agreement—would be hated. They resigned, and the king, Kaiser Wilhelm II, abdicated. These men didn’t want their fingerprints on the Armistice. A republic was declared on November 9, and the thankless task of signing the Armistice fell to Matthias Erzberger, a civilian and leader of the Catholic Centre Party, who had spoken out for peace. The humiliating list of surrender terms included a shocker: the British naval blockade would continue indefinitely even though the German soldiers had stopped fighting, and German children were starving to death. The newborn German republic, not the military, was discredited by the Armistice. Erzberger was later murdered as one of the “November criminals.”

Having enabled the French and British to win the war, Wilson imagined that he could persuade them to agree on a peace settlement according to the high-minded principles he outlined in his January 18, 1918, “Fourteen Points” speech before a joint session of Congress—principles including self-determination for peoples, freedom of the seas, and no more secret treaties. But at the Paris Peace Conference, beginning in January 1919, Wilson participated in secret diplomacy—from which the Germans were excluded—and an old-fashioned scramble among visitors for the spoils of war.

Wilson failed to stop French prime minister Georges Clemenceau. Known as “the Tiger,” Clemenceau was determined to avenge Germany’s defeat of France in 1870—a war France had started—and the loss of 1.3 million Frenchmen during World War I. Clemenceau got the notorious “war guilt” clause (Article 231) claiming that Germany was 100 percent responsible for the war, and he made sure the treaty obligated Germany to pay huge reparations and surrender a long list of assets including coal, trucks, guns, and ships—private property as well as property of the German government.

Despite Wilson’s professed ideals about self-determination, he didn’t stop the Allies from dividing German colonies among themselves. Neither the British nor the French were about to dismantle their colonial empires. The British Empire expanded by taking over the former German colonies of Tanganyika and part of Togoland and the Cameroons. Belgium and South Africa divided the rest of Germany’s holdings in Africa. To bribe Italy to enter the war on their side, the British and French had signed the secret Treaty of London (1915), which promised the Italians war spoils in Austria-Hungary, the Balkans, Asia Minor, and elsewhere, and the Italians wanted it all; they were outraged to find that the British and French planned on giving them little. The Japanese demanded Chinese territory and a statement affirming racial equality, and while they didn’t get those things, they ended up receiving German assets in China’s Shantung province, including a port, railroads, mines, and submarine cables.

Maybe the Germans deserved to be treated as they had treated others, but the harsh surrender terms, made possible by American entry in the war and enshrined in the Treaty of Versailles, further discredited the German republic and triggered a dangerous nationalist reaction. Many Germans became convinced that armed force was ultimately the only way to make up for “the shame of Versailles.” A year after the signing of the Versailles Treaty, former German corporal Adolf ****** took over the tiny German Workers Party, transformed it into the National Socialist German Workers Party, and began recruiting thousands of members by denouncing the treaty, Jews, and Bolsheviks. As far as Bolsheviks were concerned, one might say that ****** found one of his most politically useful adversaries thanks to Woodrow Wilson. Among ******’s early recruits, becoming Nazis in 1922, were Joseph Goebbels, who was to play a vital role orchestrating Nazi propaganda and mass rallies; and Rudolf Hoess, who was to manage the extermination of Jews at Auschwitz.

The reparations bill, which the Allies presented to the Germans in 1921, created powerful incentives for the Germans to inflate their currency and try paying their debts with worthless marks. Reparations weren’t the only factor in the ruinous runaway inflation—the Germans were trying to maintain a deficit-ridden welfare state, including government-run sausage factories, at the same time—but unquestionably reparations added incentives to inflate. It was no coincidence that the German inflation was worse than any other inflation following World War I. Before the war, marks were being exchanged at the rate of 4.2 per U.S. dollar, and by the end of 1923 the rate was about 4 trillion marks per dollar. The inflation wiped out life savings, made a mockery of honest contracts, disrupted production, devastated rich and poor, young and old, men and women.

****** effectively appealed to these bitter people, whom he referred to as “starving billionaires.” In a speech he gave during the summer of 1923, he told a story that illustrated the agony of inflation: “We have just had a big gymnastic festival in Munich . . . athletes from all over the country assembled here. That must have brought our city lots of business, you think. Now listen to this: There was an old woman who sold picture postcards. She was glad because the festival would bring her plenty of customers. She was beside herself with joy when sales far exceeded her expectations. Business had been good—or so she thought. But now the old woman is sitting in front of an empty shop, crying her eyes out. For with the miserable paper money she took in for her cards, she can’t buy a hundredth of her old stock. Her business is ruined, her livelihood absolutely destroyed. She can go begging. And the same despair is seizing the whole people. We are facing a revolution.”

Near the climax of the inflation, November 8, 1923, ****** made his first attempt to seize power, in a Munich beer hall where German government officials had gathered. Present for the “Beer Hall Putsch” were men who were to become key collaborators in the Nazi regime: Rudolf Hess (not to be confused with Rudolf Hoess) served as ******’s personal secretary and deputy (****** dictated the manuscript for his book Mein Kampf to Hess); Ernst Rohn, a street brawler who was an army captain during World War I, helped organize the Sturmabteilung (SA)—the brown-shirted Stormtroopers who formed ******’s first private army; Gregor Strasser was another key figure in the SA; Wilhelm Frick was a lawyer who for a while headed ******’s private armies and drafted laws for the Nazi regime; Hermann Goring, an ace fighter pilot, became a leader of the SA and later head of armed forces in Nazi Germany; Heinrich Himmler headed the Gestapo and the black-shirted Schutzstaffel (SS) secret police forces, set up the first Nazi concentration camp, and planned the Holocaust.

Suppose for a moment, that Germany had won the land war on the Western Front. How bad might that have been? The Germans showed they could be tough in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 3, 1918). As a condition for ending the war on the Eastern Front, it provided that Germany would gain large chunks of the Russian empire—including Ukraine, Georgia, Finland, and the Baltic states. These territories, though had non-Russian peoples who had long yearned to be free from Russian control. If the Germans had won on the Western Front, presumably they would have acquired territory their soldiers occupied in France and Belgium. This probably would have amounted to less than the German territory seized by the French conqueror Napoleon Bonaparte a century earlier. The rivalry between the French and Germans had been going on for a long time, and one wonders why American lives should have been sacrificed when the French and Germans got into another war.

The Germans probably wouldn’t have been able to enjoy their victory for long. Although German submarines had threatened to cut off Britain from imported food and war materials, the British countered with the convoy system; from May 1917 to November 1918 there were 1,134 convoys protecting 16,693 merchant ships, and reportedly 99 percent delivered the goods. Britain would have retained its independence, protected by its navy, which would have continued the hunger blockade against Germany. In all likelihood, Germany would have become bogged down in endemic conflicts along the vast frontier with Russia, complicated by nationalist rebellions in the wreckage of Germany’s ally, Austria-Hungary. All this probably would have proven too much for the war-weary German army, which was already struggling to put down mutinies. Such an outcome would surely have been preferable to what did happen, namely the rise of ******, World War II, and the Holocaust.

Ironically, despite Wilson’s high-minded ideals, when entering World War I he joined the side that placed a lower value on human life. British and French generals were notorious for squandering human lives—as many as 19,240 in a single day, and hundreds of thousands in a single battle. The British and French wanted American bodies to order out of the trenches into enemy machine-gun fire, replacing British and French bodies that had been thrown away in battle. At every turn the British and French resisted the idea that American soldiers should be under American command. They wanted American soldiers under the same generals responsible for so much mindless slaughter.

Almost half of American soldiers were transported to Europe in British ships, and the British relentlessly tried to break up American command units, so they could claim the soldiers would have no choice but to go into British command units and serve under British generals.

Historian John Mosier cited one of General Douglas Haig’s many blunders: “advancing in long rows at a walk was suicidal, but that was the plan. On 1 July 1916, the British infantry—all 100,000 of them—climbed out of their trenches in four distinct waves, and began to advance across to the other side. The German machine gunners could hardly believe their eyes. In two years of fighting they had never seen anything like it. As one German who was there wrote: ‘We were surprised to see them walking. We had never seen that before…. When we started to fire we just had to load and reload. They went down in their hundreds. We didn’t have to aim, we just fired into them.’”

From Thomas Woodrow Wilson: Twenty-eighth President of the United States—A Psychological Study by Sigmund Freud and William C. Bullitt); page xi (Introduction by Freud):

….the figure of the American President [Wilson], as it rose above the horizon of Europeans, was from the beginning unsympathetic to me, and…this aversion increased in the course of years the more I learned about him and the more severely we suffered from the consequences of his intrusion into our destiny.

With increasing acquaintance it was not difficult to find good reasons to support this antipathy. It was reported that Wilson, as President-elect, shook off one of the politicians who called attention to his services during the presidential campaign with words: “God ordained that I should be the next President of the United States. Neither you nor any other mortal or mortals could have prevented it.” The politician was William F. McCombs, Chairman of the Democratic National Committee. I do not know how to avoid the conclusion that a man who is capable of taking the illusions of religion so literally and is so sure of a special personal intimacy with the Almighty is unfitted for relations with ordinary children of men. As everyone knows, the hostile camp during the war also sheltered a chosen darling of Providence: the German Kaiser. It was most regrettable that later on the other side a second appeared. No one gained thereby: respect for God was not increased.

Pages xii-xiii:

Wilson . . . repeatedly declared that mere facts had no significance for him, that he esteemed highly nothing but human motives and opinions. As a result of this attitude it was natural for him in his thinking to ignore the facts of the real outer world, even to deny they existed if they conflicted with his hopes and wishes. He, therefore, lacked motive to reduce his ignorance by learning facts. Nothing mattered except noble intentions. As a result, when he crossed the ocean to bring to war-torn Europe a just and lasting peace, he put himself in the deplorable position of the benefactor who wishes to restore the eyesight of a patient but does not know the construction of the eye and has neglected to learn the necessary methods of operation.

This same habit of thought is probably responsible for the insincerity, unreliability and tendency to deny the truth which appear in Wilson’s contacts with other men and are always so shocking in an idealist. The compulsion to speak the truth must indeed be solidified by ethics but it is founded upon respect for fact.

I must also express the belief that there was an intimate connection between Wilson’s alienation from the world of reality and his religious convictions. Many bits of his public activity almost produce the impression of the method of Christian Science applied to politics. God is good, illness is evil. Illness contradicts the nature of God. Therefore, since God exists, illness does not exist. There is no illness. Who would expect a healer of this school to take an interest in symptomatology and diagnosis?

Pages 51-3:

If the reader, contemplating Wilson’s great love for his father, his great love of speech and his great hatred for many men, should be tempted to draw the conclusion from this evidence that Wilson’s libido was especially powerful, he should remember that many men give the appearance of possessing a powerful libido by concentrating its flow into a few channels; but that psychoanalysis of such men often shows that in fact the libido is weak and that, by this concentration, a great part of the psychic life has been left without sufficient flow of the libido to maintain it adequately. We know nothing about the richness of Wilson’s inner life; but we do know that the portion of his libido which flowed to the outer world was concentrated into a few channels. His range of interests was extremely narrow. Moreover, within that narrow range of interests he further concentrated the flow of his libido. One of the most striking features of Wilson’s character was what he called his “one-track mind.” He found it impossible to direct his interest to more than one intellectual object at a time. That is to say, one intellectual object was sufficient to take all the flow of his libido which found outlet through intellectual interests. This may well have been because his libido was so weak that in order to take an adequate interest in any intellectual object he had to concentrate the flow of his libido upon that object. Thus, again, it is wiser to come to no conclusion. And let us not be ashamed to admit our ignorance. To learn to say, “I don’t know,” is the beginning of intellectual integrity.

The libido of little “Tommy” Wilson, like the libido of all other human beings, first began to store itself in Narcissism and to find discharge through love of himself. The only son of his father and mother, sickly, nursed, coddled and loved by father, mother and sisters, it would have been remarkable if he had avoided a great concentration of interest on himself. He did, in fact, greatly love himself always. We can find no evidence that he was ever deficient in admiration for himself or in attention to his own aggrandizement.

Moreover, as we shall see later, to be happy he had to have a representative of himself to love. Through this love he achieved an additional outlet for the abundant charge of his libido which dwelt in Narcissism. Unquestionably a large portion of his libido continued throughout life to find outlet through Narcissism—even of the portion which discharged itself through love-objects.

Pages 259-64:

When Wilson quit in Paris, the stream of Western civilization was turned into a channel not pleasant to contemplate.

The psychological consequences of his moral collapse were perhaps as serious as the political and economic consequences. Mankind needs heroes, and just as the hero who is faithful to his trust raises the whole level of human life, so the hero who betrays his trust lowers the level of human life. Wilson preached magnificently, promised superbly, then fled. To talk and run is not in the best American tradition nor in the finest line of European development, and the Western world will not find it easy to wipe from memory the tragic-comic figure of its hero, the President who talked and ran. Our attempt to determine the exact cause and moment of Wilson’s surrender, therefore, seems to us to need no defense. It was an important surrender.

If Wilson were alive and would submit to psychoanalysis it might be possible to discover exactly why and when he abandoned the fight he had promised to make. Actually, with evidence before us, we can do no more than to indicate a possibility. It is clear that the crisis began with Wilson’s breakdown of April 3, and that it was over ten days later. Since he seemed to be utterly determined to fight on the evening of April 7 and surrendered in the important matter of reparations the next afternoon and never again fought (except over the side issue of Fiume), the conclusion seems obvious that at some time in the night of April 7 or the morning of April 8 he decided to quit. But he had told House on April 6 that he would accept the reparations “compromise,” so that his surrender of April 8 was one which he had been prepared to make; he may have made it with the firm resolve never to surrender again, and his final decision to compromise to the bitter end may have come when he received Tumulty’s telegram of April 9, which concluded: “A withdrawal at this time would be a desertion.” He may, indeed, never have made any decision but merely disintegrated.

On the other hand, after his conversation of April 6 with House he had become much more belligerent. He had ordered the George Washington and ordered credits to the Allies stopped, and throughout the day of April 7, he had seemed so utterly determined to fight that even House was astonished by the completeness of his surrender on the afternoon of April 8. Thus it is difficult to escape the impression that there had been a considerable alteration in his attitude between the evening of April 7 and the afternoon of April 8. In the absence of Wilson it is impossible to fix the moment of his collapse; but one is left with the impression that his final decision not to fight for the treaty he had promised to the world was probably made in the night of April 7. And one is tempted to imagine that he lay awake that night, facing the fear of a masculine fight which lurked in the soul of little Tommy Wilson, who had never fought a fist fight in his life, and decided to quit. That may have happened. But Wilson was not given to facing unpleasant realities, and none of his future excuses or actions indicate that he consciously recognized the truth about himself. On the contrary they indicate that he repressed the truth into his unconscious, and consciously persuaded himself that by compromising he would achieve all and more than all he might achieve by fighting.

We noted that in order to solve the inner conflict which was torturing him Wilson needed only to discover some rationalization which would permit him both to surrender and to remain in his own belief the Saviour of the World. We find that he discovered not merely one such rationalization but three! In the month which followed his compromise of April 8, 1919, he repeated over and over again three excuses. His great excuse was, of course, the League of Nations. Each time he made a compromise which was irreconcilable with his pledge to the world that the peace would be made on the basis of the Fourteen Points, he would say in the evening to his associates: “I would never have done that if I had not been sure that the League of Nations would revise that decision.” He persuaded himself that the League would alter all the unjust provisions of the treaty. When he was asked how the League could alter the treaty since the League was no Parliament of Man but on the contrary each member of the Council of the League had an absolute veto, he replied that it was true that the present League could not alter the treaty; but that the League would be altered and made stronger until it would become strong enough to alter the treaty, and that it would then alter the treaty. Thus he relieved himself of any moral obligation to fight. The moment he achieved the belief that the terms of the treaty were mere temporary expedients which could be rewritten by a permanent League, he could believe that nothing really mattered except the existence of the League. This he supremely wished to believe because the League was, he thought, his title to immortality. He closed his eyes to the fact that the League might be temporary and the terms permanent—until altered by war. In his eagerness to be the father of the League, he totally forgot his point of view of the previous year: that he could ask the American people to enter a League to guarantee the terms of the treaty only if the treaty should be so just that it would make new wars most improbable. He needed a rationalization so badly that he was able to blind himself to the fact that the League was essentially an organ to revise the very terms which it was designed to perpetuate! By the use of this rationalization he was able both to surrender and to believe that he was still the Saviour of the World.

His second excuse was and is astonishing. He was always able to find some principle to cover the nakedness of behavior which might be shocking to ordinary human decency; nevertheless it is astounding to find that he made the Treaty of Versailles as a matter of principle. He invented a magnificent sophism: He told his friends that since he had come to Europe to establish the principle of international cooperation he must support this principle and cooperate with Lloyd George and Clemenceau even at the cost of compromises which were difficult to reconcile with the Fourteen Points. He was able to fix his eyes so firmly on the words “international cooperation” that he could ignore the fact that his compromises, made in the name of the principle of international cooperation, would make international cooperation impossible. He labored for international cooperation by establishing the reparations settlement and the Polish Corridor! He applied his principle not to reality but to his conscience with such success that again he felt relieved from his obligation to fight. Indeed, it became a matter of principle not to fight! Once again, as so often in his life, a beautiful phrase had come to his rescue and slain a vicious fact that threatened his peace of mind.

His final excuse was Bolshevism. Again and again he painted word pictures of what would happen if he should fight and withdraw from the Peace Conference rather than compromise. He described the French Army marching into Germany, obliterating whole cities by chemical warfare, killing women and children, conquering all Europe and then being submerged by a Communist revolution. Again and again he repeated: “Europe is on fire and I can’t add fuel to the flames.” Thus he was finally able to convince himself that he had suppressed his personal masculine wish to fight in order to spare Europe from the dreadful consequences which would have followed his release of his masculinity. It became self-sacrificing of him not to fight. By this somewhat circuitous route he managed to bring further support to his conviction that he had sacrificed himself for the welfare of humanity, and therefore resembled Christ.

Wilson seems to have accepted these rationalizations fully and finally in the second week of April 1919. He wanted to believe in their validity, therefore he believed. Thus, most satisfactorily to him, he escaped from the inner conflict which tortured him. But all his excuses were based on the ignoring of facts, and facts are not easy to ignore. A man may repress knowledge of an unpleasant fact into his unconscious; but it remains there struggling to escape into consciousness and he is compelled to repress not only his memory of it but of all closely associated facts in order to continue to forget it. His mental integrity becomes impaired, and he moves steadily away from the fact making greater and greater denials that the fact exists. The man who faces facts, however unpleasant they may be, preserves his mental integrity. The facts which Wilson had to face were, to be sure, most unpleasant: He had called his countrymen to follow him on a crusade and they had followed him with courage and conspicuous self-abnegation; he had promised them and the enemy and, indeed, all mankind a peace of absolute justice based upon his Fourteen Points; he had preached like a prophet who was ready to face death for his principles; and he had quit. If, having quit, instead of inventing soothing rationalizations, Wilson had been able to say to himself, I broke my promises because I was afraid to fight, he would not have disintegrated mentally as he disintegrated after April 1919. His mental life from April to September 1919, when he collapsed completely and permanently, was a wild flight from fact. This mental disintegration is an additional indication that in the second week of April 1919 he could not face his femininity and fear but merely embraced with finality the rationalizations which enabled him to avoid looking at the truth. At the crisis of his life he was in fact overwhelmed once more by his passivity to his father and by fear. But he seems never to have let his knowledge of this fact rise into his consciousness. It seems clear that when he decided to allow the Fourteen Points to be transformed into the Treaty of Versailles he was conscious of only the most noble motives. He betrayed the trust of the world as a matter of principle.

From A President in Love: The Courtship Letters of Woodrow Wilson and Edith Bolling Galt (edited by Edwin Tribble); page x (Introduction):

In the spring of 1915, when Woodrow Wilson was struggling with the gravest and most far-reaching decisions any American President had ever been called upon to make, he fell deeply, heedlessly, boyishly in love. Public affairs waited while he spent hours writing long letters to the woman he loved and reading and re-reading her replies. This is the story of that romance, based on a correspondence only now made available to the public, letters unique in Presidential history for their passion and zeal.

Wilson was then the most powerful man in the world. A great and widening war was raging in Europe, and the course this nation took would determine who would win it. Winston Churchill, writing many years later in The World Crisis, put this into its proper perspective:

“It seems no exaggeration to pronounce that the action of the United States with its repercussions on the history of the world depended, during the awful period of Armageddon, upon the workings of this man’s mind and spirit to the exclusion of almost every other factor; and that he played a part in the fate of nations incomparably more direct and personal than any other man.”

Page xvi:

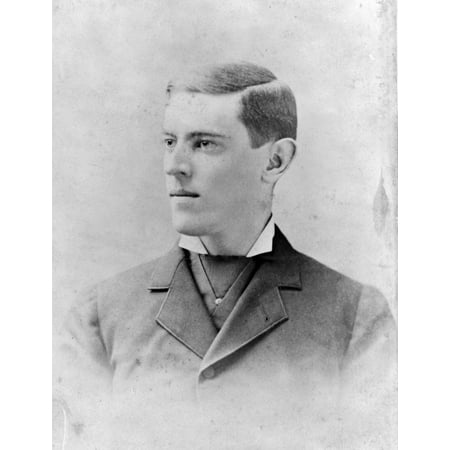

Woodrow Wilson was fifty-eight, an impressive man who had assumed naturally the role of leader of 100 million people. Personally, he was lithe and active, described by a friend as “keen, sharp-cut, spare in mind as in feature, deft in his movements, a silent, intense worker, a lover of intellectual athletics, delighting in new and strong ideas.” Weighing about 175 pounds, he was five feet eleven inches tall, with gray-blue eyes and hair lightly touched with gray. A severe stroke in 1906 had left him with a slight defect in his left eye, and he wore pince-nez eyeglasses, the style of the time. He had been a lawyer (briefly), a teacher, university president, and governor of New Jersey. A professional writer, he was the author of books of history and political science as widely admired for their literary qualities as for their factual content and philosophy. His style, formal by modern standards, was in the academic tradition of his time.

Pages xvii-xviii:

He [Wilson] was called a Puritan (although he liked an occasional Scotch highball and enjoyed wine), and there is evidence of strict moral judgments in his papers, both public and private. He was generally described as complicated, although modern authorities consider him fundamentally a simple predictable man. However, analysts from famous professionals to members of his own family tried to explain what they felt were inner conflicts and contradictions. Sigmund Freud (in Thomas Woodrow Wilson: A Psychological Study, written with William C. Bullitt), advanced theories as varied as the generally accepted one that “the rapid turning from his dead wife to Mrs. Galt was proof rather than disproof of his affection for the former,” to his original one of the influence of the President’s father upon him.

And there are many far homelier conclusions, tossed off at random by less sophisticated thinkers but containing, perhaps, their own grains of truth about Wilson when he was alive. His sister-in-law, Margaret Axson Elliott, wrote of him in her memoir My Aunt Louisa and Woodrow Wilson: “He was too thin-skinned to get out and wrestle with the ‘tough guys.’” Edith Gittings Reid, an old friend from Baltimore, aimed for the widest possible explanation in her book Woodrow Wilson: The Caricature, the Myth and the Man: “He believed that ideals could be put to practical use and be lived, and on that rock he broke, as all humanitarian idealists who have taken Christ as Exemplar must break.” In all his life it is easy to see him moving from simple conscience to moral grandeur.

Pages xix-xx:

The style of Wilson’s letters is one of romantic exuberance, sometimes overdone, and frequently there is an oratorical ring to them; he was, after all famous as a speaker. The letters are almost entirely devoid of humor. Newspaper reports of his speeches sometimes referred to him as a witty man, but there is little sign of it here. His friends said that he had a light side and that he told stories with a sly sense of the ludicrous. He was especially known for his Southern “darkey” stories, which were perfectly acceptable, even admired, in his day. A typical one, as recalled by one of his friends, was about an old preacher praying, during the 1886 earthquake in Charleston, “Oh, Lord, come and save us. Don’t send your son, Lord, come yourself. This ain’t no time for chillun.” And there is a letter (elsewhere) in which he revealed what he did not like when he mentioned seeing “that terrible play of Oscar Wilde’s, Lady Windermere’s Fan.”

Page 2 (“April 1915”) [context]: