View Poll Results: Leo Tolstoy

- Voters

- 2. You may not vote on this poll

-

Alpha

-

Beta

-

Gamma

-

Delta

-

ILE (ENTp)

-

SEI (ISFp)

-

ESE (ESFj)

-

LII (INTj)

-

EIE (ENFj)

-

LSI (ISTj)

-

SLE (ESTp)

-

IEI (INFp)

-

SEE (ESFp)

-

ILI (INTp)

-

LIE (ENTj)

-

ESI (ISFj)

-

LSE (ESTj)

-

EII (INFj)

-

IEE (ENFp)

-

SLI (ISTp)

-

WE'RE ALL GOING HOME

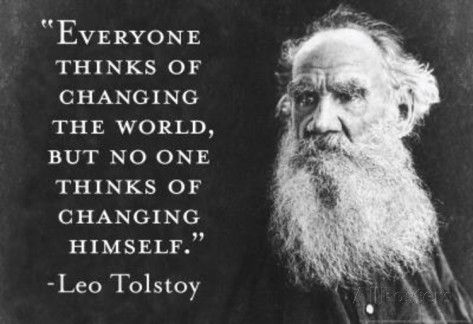

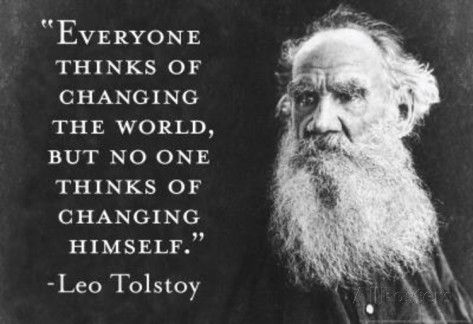

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy

Tolstoy: ESI

Anna Karenina (trans. Kyrill Zinovieff & Jenny Hughes); p. 689-93 (Pt. 7, Ch. 28 & 29):

The weather was clear. A fine drizzle had been falling all the morning, and now it had just cleared up. The iron roofs, the flagstones of the pavement, the cobbles in the roadway, the wheels and the leather, the brass and the metalwork of carriages – everything glistened brightly in the May sunshine. It was three o’clock, the time when streets are at their most lively.

Sitting in the corner of the comfortable carriage, swaying only slightly on its resilient springs with the swift trot of the greys, Anna again went over in her mind – to the ceaseless rattle of the wheels and the rapidly changing impressions in the open air – the events of the last few days and saw her situation in quite a different light to what it had seemed to her at home. Even the thought of death did not seem to her now as clear and terrifying, and death itself did not appear inevitable. Now she reproached herself for the depths of humiliation to which she had descended. “I am imploring him to forgive me. I gave in to him. Admitted I was in the wrong. Why? Can’t I live without him?” And leaving unanswered the question of how she was going to live without him, she began reading the signboards. “Office and Warehouse. Dental Surgeon. Yes, I’ll tell Dolly everything. She doesn’t like Vronsky. It’ll be humiliating, painful, but I’ll tell her everything. She is fond of me and I’ll follow her advice. I will not give in to him, I won’t allow him to mould my character. Filippov, Cakes. They say they send their pastry to Petersburg. Moscow Water is so good. And then the Mytishchi Wells and Pancakes.” And she recalled how long, long ago, when she was only seventeen, she had visited the Trinity Monastery with her aunt. “It still had to be by horse and carriage. Was it really me, with red hands? What a lot of things that then seemed to me so marvellous and unattainable, have become insignificant, and the things I had then are now unattainable for ever! Would I have believed then that I could reach such depths of humiliation? How proud and happy he’ll be when he gets my note! But I will show him… What a nasty smell this paint had. Why do they go on painting and building all the time? Dress-making and Millinery,” she read. A man bowed to her. It was Annushka’s husband. “Our parasites,” she remembered Vronsky saying. “Our? Why our? The terrible thing is that the past can’t be torn out by its roots. It can’t be torn out, but it can be ignored. And I shall ignore it.” And here she remembered her past with Karenin and how she had blotted it out from her memory. “Dolly will think that I’m leaving a second husband and that therefore I must surely be in the wrong. As if I had any wish to be in the right! I can’t!” she murmured and wanted to cry. But immediately she started wondering what those two girls were smiling at. “Love, probably? They don’t know how dreary it is, how humiliating… the Avenue and children. Three boys running, playing at horses, Seryozha! I shall lose everything and not get him back. I shall, I’ll lose everything if he doesn’t come back. Perhaps he has missed the train and is back by now. Want more humiliation!” she said to herself. “No, I’ll go in to Dolly and tell her straight out: ‘I’m unhappy, I deserve it, the fault’s mine, but I’m unhappy all the same, help me.’ These horses, this carriage – how I loathe myself in this carriage – they’re all his; but I shall never see them again.”

Thinking up the words she would use to tell Dolly everything and deliberately putting salt on her wounded heart, Anna went up the steps.

“Any guests?” she asked in the hall.

“Yekaterina Alexandrovna Levin,” replied the servant.

“Kitty! The Kitty Vronsky had been in love with,” thought Anna, “the girl he always remembered with affection. He is sorry he did not marry her. But me he thinks of with loathing and is sorry he has ever started this love affair.”

The two sisters were having a consultation about feeding the baby when Anna arrived. Dolly came out alone to meet her guest, who was preventing them from going on with their conversation.

“Ah, you haven’t left yet? I wanted to come and see you myself,” she said. “I received a letter from Stiva today.”

“We’ve also received a telegram,” replied Anna, looking round to see Kitty.

“He writes that he doesn’t understand what Alexei Alexandrovich really wants, but that he won’t leave without an answer.”

“I thought you had someone with you. May I read the letter?”

“I have – Kitty,” said Dolly embarrassed. “She has stayed in the nursery. She has been very ill.”

“So I’ve heard. May I read the letter?”

“I’ll bring it right away. But he has not refused; on the contrary, Stiva has hopes,” said Dolly, pausing in the doorway.

“I have no hope and, besides, I don’t want it,” said Anna.

“What’s this? Does Kitty think it beneath her dignity to meet me?” thought Anna when she remained alone. “She may be right, too. But it’s not for her, her, who was in love with Vronsky, to let me see it, even though it’s true. I know that no respectable woman can receive me in my present situation. I knew that from that very first moment I sacrificed everything to him. And here’s the reward! Oh, how I hate him. And what did I come here for? I feel worse here, feel the situation more difficult to bear.” She heard the sisters’ voices conferring in the next room. “And what shall I tell Dolly now? Shall I comfort Kitty with the knowledge that I am unhappy and submit to her patronage? No, and, besides, Dolly won’t understand anything. And I have nothing to say to her. It would be interesting only to see Kitty and show her how I despise everyone and everything, how nothing matters to me now.”

Dolly came in with the letter. Anna read it and handed it back in silence.

“I knew it all,” she said. “And it doesn’t interest me in the least.”

“But why? I have hopes, on the contrary,” said Dolly, looking at Anna with curiosity. She had never seen her in such a strange, irritable mood. “When are you going?” she asked.

Anna looked straight in front of her, screwing up her eyes, and did not answer.

“Why is Kitty hiding from me?” she said, looking at the door and blushing.

“Oh, what nonsense. She is feeding the baby and is having some trouble, I advised her… she’s delighted. She’ll come in a minute,” said Dolly awkwardly, bad at lying. “Ah, there she is.”

When she was told that Anna had arrived, Kitty had not wanted to come out, but Dolly had persuaded her. Kitty came out, nerving herself to do it, and blushed as she came up to Anna and held out her hand.

“I am delighted,” she said, in a shaky voice.

Kitty was embarrassed by the struggle that was taking place within her between animosity towards this bad woman and the desire to be forbearing; but as soon as she saw Anna’s lovely, pleasant face, all hostility immediately vanished.

“I shouldn’t have been surprised if you had refused to see me. I am used to everything. You were ill? Yes, you’ve changed,” said Anna.

Kitty felt that Anna was looking at her with hostility. She put it down to the awkward situation which Anna, who had once befriended her, now felt herself to be in in her presence, and she was sorry for her.

They chatted about Kitty’s illness, about the child, about Stiva, but quite obviously nothing interested Anna.

“I came to say goodbye to you,” she said to Dolly.

“When are you going, then?”

But again Anna did not answer and turned to Kitty.

“Yes, I’m very glad I saw you,” she said with a smile. “I’ve heard so much about you from so many sources, even from your husband. He came to see me and I liked him very much,” she added with obvious ill intention. “Where is he?”

“He has gone to the country,” said Kitty blushing.

“Remember me to him – be sure you do.”

“I will be sure to,” repeated Kitty naively, and had a feeling of pity for her as she looked into her eyes.

“Well then, goodbye, Dolly.” And Anna hastily left, having kissed Dolly and shaken hands with Kitty.

“She’s the same as ever and just as attractive. Very beautiful!” said Kitty, when Anna was gone. “But there’s something pathetic about her. Terribly pathetic.”

“No, there was something special about her today,” said Dolly. “When I was seeing her off in the hall I had the impression she wanted to cry.”

…

Anna got into the carriage feeling worse even than she had when she had left home. To her previous agony was now added the feeling of humiliation and rejection which she had clearly felt during the meeting with Kitty.

“Where now? Home?” asked Pyotr.

“Yes, home,” she said no longer even thinking of where she was going. “How they looked at me – as at something terrible, strange and curious. What can he be telling the other man?” she thought, glancing at two pedestrians. “How can one tell someone else what one feels! I was going to tell Dolly and it’s a good thing I didn’t. How she would have been delighted at my misery! She would have concealed it, but her main feeling would have been joy at my being punished for the pleasures she envied me for. And Kitty – she would have been even more delighted. How I can see the whole of her – through and through! She knows I had been more than usually polite to her husband. And she is jealous and hates me. And despises me, too. In her eyes I am an immoral woman. If I were an immoral woman I could have made her husband fall in love with me… had I wanted to. And I did want to, too. Now, that man is pleased with himself,” she thought, seeing a fat, red-faced gentleman driving past in the opposite direction, who had taken her for someone he knew, had raised his shiny hat over his shiny bald head and then discovered he had made a mistake. “He thought he knew me. But he knows me as little as anyone in the world knows me. I don’t know myself. I know my appetites, as the French say. Now those boys there want that filthy ice cream. This they know for sure,” she thought, looking at two boys who had stopped an ice-cream man; the man took a tub down from his head and was wiping his sweaty face with the end of a cloth. “We all want something sweet, something that tastes nice. If we can’t have candy, give us filthy ice cream. And Kitty is the same: couldn’t get Vronsky, so she took Levin. And she envies me. And hates me. And we all hate each other. I hate Kitty, and Kitty me. Yes, this is true. Tyutkin, coiffeur, je me fais coiffer par Tyutkin… [Tyutkin, hairdresser, I have my hair done by Tyutkin…] I’ll tell him this when he comes,” she thought and smiled. But all at once she remembered she had no one now to say funny things to. “Besides, there’s nothing funny, nothing amusing anywhere. Everything is horrible. They’re ringing the bell for Vespers and how carefully that shopkeeper crosses himself! As if he is afraid of dropping something. What are these churches for, that bell-ringing and that falsehood? Only in order to conceal the fact that we all hate each other, like those cabdrivers who swear at each other with such venom. Yashvin says: ‘He wants to leave me without a shirt and I want to leave him without one.’ That’s the truth.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=in58wtVI9sI

p. 693-700 [Pt. 7, Ch. 29-31]:

She was so absorbed by these thoughts that she even forgot to think about her own situation, when her carriage drew up at the steps of her house. Only on seeing the doorman come out to meet it did she remember that she had sent a note and a telegram.

“Any answer?” she asked.

“I’ll have a look,” replied the doorman and after a glance at his desk took out and gave her the thin square envelope of a telegram.

“Cannot come before ten o’clock. Vronsky,” she read.

“And has the messenger come back?”

“No, he hasn’t,” replied the porter.

“Ah, in that case I know what I have to do,” she said and feeling a vague anger and need for vengeance rising within her, she ran upstairs. “I’ll go to him myself. Before leaving him for ever I shall tell him everything. Never, never have I hated anyone as much as I hate this man!” she thought. On seeing his hat on the peg she shuddered with loathing. It did not occur to her that his telegram was a reply to her telegram and that he had not received her note yet. She imagined him now talking calmly with his mother and Princess Sorokin and rejoicing at her sufferings. “Certainly I must go as soon as possible,” she said to herself, not knowing yet where to go. She wanted to get away as quickly as she could from the feelings she experienced in that terrible house. The servants, the walls, the things in that house – it all evoked loathing and fury within her and pressed her down like a weight.

“I must go to the railway station or else go there, to the house, and catch him.” Anna looked up the railway timetable in the newspaper. A train was leaving in the evening at 8.20. “Oh yes, I’ll have time.” She ordered other horses to be harnessed and began packing a travelling bag with things she would need for several days. She knew she would never return. Among all the plans that came into her head she vaguely decided on one which was that after what would take place at the railway station or at the Countess’s estate, she would go by the Nizhny Novgorod line as far as the first town and stay there.

Dinner was laid; she went up to the table, smelt the bread and the cheese and, having come to the conclusion that the smell of all food disgusted her, ordered her carriage and went out. The house already threw its shadow right across the street, and the evening was clear and still warm in the sun. And Annushka who was following her with her things, and Pyotr who was putting the things in the carriage and the coachman, obviously disgruntled – she found them all repulsive and their words and gestures irritated her.

“I don’t need you, Pyotr.”

“But what about the ticket?”

“Oh, as you like, I don’t care,” she said, vexed.

Pyotr jumped on to the box and, arms akimbo, ordered the coachman to drive to the station.

…

“There’s that girl again! Again I understand everything,” said Anna to herself as soon as the carriage moved off and, swaying a little, rattled over the small cobbles of the roadway; and again impressions succeeded each other in her head.

“Oh yes, what was the last thing I was thinking of? It was rather good,” she said to herself, trying to remember. “Tyutkin, coiffeur? No, that wasn’t it. Oh yes – what Yashvin was saying: the struggle for existence and hatred are the only things that bind people together. No, it’s no use you going,” she said, mentally addressing a party of people in a four-in-hand, who were evidently driving off to the country on pleasure bent. “And the dog you are taking with you won’t help you. You can’t get away from yourselves.” Glancing in the direction in which Pyotr was looking she saw a half-drunk factory worker, his head swaying, being led away by a policeman. “Now that one’s done it quicker,” she thought. “Count Vronsky and I also failed to find any joy, even though we expected so much from it.” And now for the first time Anna turned that bright light by which she was seeing everything on her relations with him, which up till now she had avoided thinking about. “What did he look for in me? Not so much love as the satisfaction of his vanity.” She recalled his words and the expression on his face, reminiscent of a docile pointer, in the early days of their liaison. And everything now confirmed this. “Yes, he felt the triumph of successful vanity. Of course, there was some love in it too, but it was mainly pride in his success. I was something for him to boast about. Now that’s past. There is nothing to be proud of. Not to be proud of, but to be ashamed of. He took from me all he could and now I am no use to him. He finds me a burden and is trying not to behave dishonourably towards me. He let the cat out of the bag yesterday when he said what he said – he wants the divorce and marriage in order to burn his boats. He loves me – but how? The zest is gone,” she said to herself in English. “This man wants to astonish everyone and is very pleased with himself,” she thought, looking at a pink-faced shop assistant riding a hired horse. “He finds all the savour gone, so far as I am concerned. If I leave him, in his heart of hearts he will be pleased.”

This was no supposition; she saw it clearly in that piercing light which now revealed to her the meaning of life and of human relations.

“My love is becoming more passionate and selfish all the time, and his is gradually fading, and this is why we are drifting apart,” she went on thinking. “And there’s nothing that can be done about it. I have staked everything on him and I demand from him an increased devotion to me. But he wants to get further and further away from me. Before our liaison we were drawn towards each other, but now we are being irresistibly drawn apart. And nothing can change it. He tells me I am jealous for no reason and I used to tell myself I was jealous for no reason; but this isn’t true. I’m not jealous, but I am displeased. But…” She opened her mouth and moved to another seat in the carriage from the sheer excitement aroused by the thought that suddenly occurred to her. “If I could be anything other than his mistress who passionately loves his caresses; but I can’t be anything else and don’t want to be. And by this desire of mine I arouse revulsion in him and he anger and resentment in me, and it cannot be otherwise. As if I didn’t know he would not deceive me, that he has no designs on the Sorokin girl, that he is not in love with Kitty, that he will not be unfaithful to me! I know all this, but I’m none the happier for it. If he becomes kind and tender to me not because he loves me but out of a sense of duty, while what I desire will simply not be there – why, that would be a thousand times worse even than resentment. It would be hell! And it’s precisely what is happening. He has long stopped loving me. And where love stops hate begins. I don’t know these streets at all. All these hills and these houses, endless houses… And the houses are filled with people and more people… So many of them, there’s no end to them and they all hate each other. All right, let’s say I think up something which will make me happy. Well? I get a divorce, Karenin gives up Seryozha to me and I get married to Vronsky.” At the thought of Karenin, an extraordinarily vivid picture of him rose up before her eyes, very true to life with his meek, lifeless, dull eyes, blue veins on white hands, tone of voice and cracking of fingers, and the recollection of the feeling which had existed between them and which had also been called love, made her shudder with revulsion. “All right then, I’ll get my divorce and shall become Vronsky’s wife. And so Kitty will no longer look at me the way she looked at me today? No. And will Seryozha no longer ask or think about my two husbands? And what sort of new emotion will I think up between me and Vronsky? Is anything possible – which will not be happiness, of course, but will not be agony either? No, no and no!” she answered herself without the slightest hesitation now. “It is not possible. Life itself is drawing us apart, and I’m the cause of his unhappiness and he of mine; he can’t be changed and nor can I. We’ve tried everything but the screw has worn smooth. Oh yes, there’s a beggar woman with her child. She thinks people are sorry for her. Aren’t we all thrown out into the world only in order to hate each other and therefore to torment ourselves and others? Schoolboys walking out there, laughing. Seryozha?” she thought. “I also thought I loved him and admired my own tenderness. But I did, after all, live without him, did give him up in exchange for another love, and did not complain about the exchange, so long as I was satisfied with that other love.” And she remembered with revulsion what she called that other love. And the clarity with which she now saw her own and other people’s lives made her glad. “That’s how I am, and Pyotr, and Fyodor the coachman, and that tradesman, and all those people who live along the Volga where those advertisements invite us to, and everywhere and always,” she thought as she drove up to the low building of the Nizhny Novgorod station and the porters ran out to meet her.

“Shall I get a ticket to Obiralovka?” said Pyotr.

She had quite forgotten where to and why she was travelling and understood the question only with great effort.

“Yes,” she said, handing him her purse and, taking a small red bag in her hand, she stepped out of the carriage.

As she made her way through the crowd to the first-class waiting room, she remembered little by little all the details of her situation and the various choices she was hesitating between. And again hope and despair in turn touched the old sore places and rubbed salt into the wounds of her aching, her terribly fluttering heart. Sitting on the star-shaped sofa waiting for the train and looking with loathing at the people coming in and out (they all seemed repulsive to her), she thought of how she would arrive at the station and would write a note to him and of what she would write; she thought of how, in his inability to understand her sufferings, he was now complaining to his mother of the situation he found himself in, and of how she would come into the room, and of what she would say to him. Then she thought of how life might still be happy, and of how agonizingly she loved and hated him and of how terrible was the pounding of her heart.

…

The bell rang, some young men went hurriedly by, ugly and insolent and yet careful of the impression they were creating; Pyotr, in his livery and gaiters, with his vacuous, brutish face, also crossed the hall and came up to her in order to see her to her railway carriage. The noisy men became quiet when she passed them on the platform and one of them whispered something about her to another – something horrid, naturally. She climbed up the high step of the carriage and sat down in an empty compartment on the dirty well-sprung seat which had once been white. The springs of the seat made her bag bounce once before it lay still. Pyotr, with an inane smile raised his gold-braided hat by way of saying goodbye to her, and an insolent guard slammed the door and banged down the catch. A lady, ugly and wearing a bustle (Anna mentally undressed the woman and was appalled at her hideousness), and a little girl ran past the carriage window laughing affectedly.

“Katerina Andreyevna’s got it, she’s got it all, ma tante,” shouted the girl.

“Even the girl is unnatural and affected,” thought Anna. To avoid seeing anyone she quickly got up and sat down at the opposite window of the empty compartment. A grimy, ugly peasant with strands of matted hair sticking out from under his cap went past the window, stooping down to the carriage wheels. “There is something familiar about that hideous peasant,” Anna thought. Then she remembered her dream and went over to the opposite door trembling with fear. The guard was opening the door to let in a man and his wife.

“Are you getting out, madam?”

Anna did not reply. Neither the conductor nor the passengers coming in noticed the terror on her face under her veil. The couple sat down opposite her, and examined her dress with some attention, though trying not to show it. Both husband and wife seemed repulsive to Anna. The husband asked her for permission to smoke, obviously not in order to smoke but in order to start a conversation with her. On receiving her permission, he began to speak to his wife in French about something he had even less need to speak about than he had to smoke. Pretending to talk, they spoke nonsense only so that she should hear. Anna saw clearly how sick they were of each other and how much they hated one another. Indeed, it was impossible not to hate such pathetic monsters.

The second bell rang, followed by luggage being moved, by noise, shouting and laughter. It seemed so clear to Anna that no one had anything to rejoice about that the laughter irritated her to the point of physical pain and she wanted to stop her ears so as not to hear it. The third bell rang at last, the engine whistled and screeched, the coupling chain jerked and the husband crossed himself. “It would be interesting to ask him what he means by this,” thought Anna, glancing up at him with hatred. She was looking past the lady, out of the window, at the people seeing the train off, who were standing on the platform and appeared to be gliding backwards. Jerking rhythmically over the rail joints the carriage in which Anna was sitting rolled past the platform, past a stone wall, past the signals, past other carriages; the wheels with a movement ever more oily-smooth, gave a slight ringing sound as they rolled on the rails, the window was lit up by the bright evening sun, and a light breeze played with the blind. Anna forgot about her fellow-passengers and, rocked gently by the movement of the train, breathed in the fresh air and resumed her thoughts.

“Oh yes, what was it I was thinking of? Of the fact that I couldn’t conceive of a situation in which life would not be a torment, that we are all created in order to suffer, and that we all know this and are all busy thinking up different ways of self-deception. But when you see the truth what are you to do?”

“Man is given reason to be rid of his worries,” said the lady in French, obviously pleased with her phrase and saying it in an affected accent.

Those words seemed to answer Anna’s thought.

“To be rid of worries,” repeated Anna. And glancing at the ruddy-faced husband and his thin wife she realized that the sickly wife believed herself to be a misunderstood woman and the husband was unfaithful to her and encouraged her in her belief. By turning her searchlight on them, Anna seemed to know their history and all the nooks and crannies of their souls. But there was nothing of any interest there and she resumed her train of thought.

“Yes, I am very worried and reason is given to man to be rid of worries; therefore I must get rid of them. Why not snuff out the candle when there’s nothing more to look at, when all is loathsome to see? But how? Why did that guard run along the footboard? Why do they shout, those young men in that carriage? Why do they talk, why do they laugh? It is all lies, all falsehood, all deceit, all evil…”

When the train stopped at a station Anna came out in a crowd of other passengers and, shunning them like lepers, stood on the platform trying to remember why she had come there and what she had intended doing. Everything that before seemed possible to her was now so difficult to grasp, particularly in all that noisy crowd of ugly people who never left her in peace. The porters were running up and offering their services; young men, tapping the wooden floor of the platform with their heels, were talking in loud voices and looking her up and down; people trying to get out of her way dodged the wrong way. Recollecting that she had meant to continue her journey if there was no answer, she stopped a porter and asked whether there was a coachman there with a note from Count Vronsky.

“Count Vronsky? Someone from him has just been here. Meeting Princess Sorokin and her daughter. What’s the coachman like?”

While she was speaking to the porter, the coachman, Mikhail, pink-cheeked and cheerful, dressed in a smart blue coat with a watch chain, evidently proud of having carried out his errand so well, came up to her and handed her a note. She unsealed the envelope and felt a pang in her heart even before she had read it.

“Very sorry your note did not catch me. I’ll be back at ten,” Vronsky had written in a careless hand.

“There! That’s what I expected!” she said to herself with a contemptuous little laugh.

“All right, go home then,” she said softly, turning to Mikhail. She spoke softly because the rapid pounding of her heart interfered with her breathing. “No, I shan’t let you torment me,” she thought, directing her threat not at him, not at herself, but at whoever it was made her suffer, and went along the platform past the station building.

Two servant-girls walking up and down the platform turned their heads round to look at her and commented on her dress: “Real,” they said about the lace she was wearing. The young men would not leave her in peace. They went past her again, peering into her face, laughing and shouting out something in unnatural voices. The station master asked her, as he walked by, whether she was going on in the train. A boy selling rye beer never took his eyes off her. “Oh God, where am I to go?” she thought going further and further along the platform. At the end of it she stopped. A few ladies and children who had come to meet a bespectacled gentleman, and had been laughing and talking in loud voices, fell silent and stared at her when she drew even with them. A goods train was approaching. The platform shook and she had the impression she was going in the train again.

And suddenly she remembered the man crushed by the train the day she had first met Vronsky, and realized what she had to do. With a swift, light tread she went down the steps leading from the water tank to the rails and stopped close to the passing train. She was looking at the underside of the trucks, at the screws and chains, and at the tall iron wheels of the first truck slowly rolling forwards, and tried to estimate the point midway between the front and back wheels and the precise moment at which that midway point would be opposite her.

“There!” she said to herself, looking in the shadow of the truck at the mixture of sand and slag which covered the sleepers, “there, right in the middle, and I’ll punish him and escape from them all and from myself.”

She wanted to fall under the first truck, the middle portion of which was now directly opposite her. But the little red bag, which she began to take off her arm, delayed her and it was too late: the middle of the truck had already passed her. She had to wait for the next truck. A feeling similar to the one she used to have, when about to enter the water bathing, seized her and she made the sign of the cross. The familiar gesture of crossing herself evoked within her a whole series of memories of her childhood and youth, and suddenly the darkness that had shrouded everything for her was torn apart and life appeared before her for a moment, radiant with all its past joys. But she did not take her eyes off the wheels of the second truck, which was now approaching. And at precisely the moment when the midpoint between the wheels drew level with her, she threw aside the little red bag and, drawing her head in between her shoulders, dropped on her hands under the truck and with a light movement, as if about to rise at once, she sank to her knees. And at that same instant, she was horror-struck at what she was doing. “Where am I? What am I doing? Why?” She tried to rise, to throw herself aside; but something huge and inexorable struck her on the head and dragged her along by her back. “God, forgive me everything!” she murmured, feeling the impossibility of struggling. A little peasant, muttering something, was working over some iron. And the candle by which she had read the book filled with anxiety, deceit, sorrow and evil flared up with a brighter light than ever, lit up for her all that before had been in darkness, spluttered, grew dim and went out for ever.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jfK-OI3oXWQ

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r6rqCy83EcA

p. 462-76 (Pt. 5, Ch. 21-25):

Once Karenin realized, from his talks with Betsy and Oblonsky, that all that was required of him was that he should leave his wife in peace and not trouble her with his presence and that his wife herself desired this, he felt so lost that he could not decide anything himself, did not himself know what he wanted and, putting himself in the hands of those who took such pleasure in looking after his affairs, he agreed to everything. Only when Anna had actually left the house and the English governess sent to enquire whether she should dine with him or separately, did he for the first time clearly realize his position and was appalled by it.

The most difficult thing about his situation was that he was quite unable to find a link or reconcile his past with what was taking place now. It was not the past, during which he had lived happily with his wife, that disturbed him. He had already lived through the agony of transition from the past to the knowledge of his wife’s infidelity; that state had been painful to him but he found it comprehensible. If his wife had left him then, after confessing to her infidelity, he would have been grieved and unhappy but he would not have been in the same hopeless, to him incomprehensible, situation in which he now felt himself to be. He was quite unable to reconcile his recent forgiveness of her, his emotion of tenderness, his love for his sick wife and for another man’s child, with what was happening now: with the fact that his reward was to find himself now alone, disgraced, ridiculed, not wanted by anyone and despised by all.

During the first two days after his wife’s departure Karenin received petitioners, saw his private secretary, went to committee meetings, and had dinner in the dining room as usual. Without realizing why he was doing so, during these two days he stretched every nerve and thought with the sole aim of appearing calm and even indifferent. When replying to the servants’ enquiries as to what should be done with Anna’s rooms and belongings, he made a supreme effort to appear like a man for whom the event which had taken place had not been unforeseen and had nothing out of the ordinary about it, and he achieved his aim: no one could have discerned in him any signs of despair. But on the third day after Anna’s departure, when Korney handed him a bill from a milliner’s shop which she had forgotten to pay and informed him that the manager had come in person, Karenin had him shown up.

“Forgive me, sir, for being so bold as to trouble you. But if you would like us to send the bill to madam, then would you be good enough to let us have madam’s address?”

Karenin seemed to the shopkeeper to be pondering, and then suddenly turned around and sat down at the table. His head sunk in his hands, he sat there in that position for a long while, several times attempting to say something and stopping short.

Korney, who had understood his master’s feelings, asked the shopkeeper to call another time. Left alone once more, Karenin realized that he was no longer capable of keeping up the appearance of firmness and calm. He gave orders for the carriage, which was waiting, to be unharnessed, said that he would receive no one, and did not appear at dinner.

He felt he would not be able to endure that general pressure of contempt and harshness, which he had clearly seen on the face of the shopkeeper and of Korney, and of everyone, without exception, whom he had met during those two days. He felt that he could not avert people’s hatred from himself, for the hatred was there not because he was bad (for then he could have tried to be better) but because he was shamefully and repulsively unhappy. He knew for that very reason – because his heart was torn to shreds – they would be merciless to him. He felt that people would destroy him like dogs who tear out the throat of some poor maimed dog whining in pain. He knew that the only hope of escape from people was to hide his wounds from them and he had unconsciously tried to do this for two days, but now he felt that it was beyond him to carry on this unequal struggle any longer.

His despair was further increased by the consciousness that he was entirely alone in his grief. It was not just that there was not a single person in Petersburg to whom he could tell everything he was experiencing, who might pity him not as a high-ranking civil servant, not as a member of society, but just as a suffering human being; it was that he had no such friend anywhere.

Karenin had grown up an orphan, together with his only brother. They did not remember their father; their mother had died when Karenin was ten years old. They had small means. They had been brought up by Karenin’s uncle, an important civil servant and sometime favourite of the late Emperor.

Having finished school and university with distinction, Karenin, with the help of his uncle, had at once embarked on a distinguished civil service career and, from then on, had entirely devoted himself to professional ambition. Neither at school nor at university, nor later at work, had Karenin made close ties of friendship with anyone. His brother had been the person closest to his heart, but he had been in the diplomatic service and had always lived abroad where, indeed, he had died, shortly after Karenin’s marriage.

It was when Karenin had been Governor of a province that an aunt of Anna’s, a rich provincial lady, had introduced him – no longer a young man, though a young Governor – to her niece, and had manoeuvred him into such a position that he either had to propose to her, or leave the town. Karenin had hesitated for a long time. There were, at the time, just as many reasons for this step as there were against it, and there was no decisive reason to make him change his rule: when in doubt, refrain. But Anna’s aunt had intimated to him through a mutual acquaintance that he had already compromised the girl and that he was in honour bound to propose to her. He did so, and bestowed upon his bride and wife all the feeling of which he was capable.

His attachment to Anna excluded from his heart any vestige of a need he may have felt for affectionate relations with other people. And now, among all his acquaintances, he had not a single close friend. He had many so-called social connections; but no friends at all. Karenin knew a great many people whom he could invite to dinner, whom he could ask to take part in a project which interested him or whose influence he could use on behalf of a petitioner, or with whom he could frankly discuss the activities of other people and of the government; but his relations with these people were limited to one sphere, sharply defined by custom and habit, beyond which it was impossible to go. He did have one acquaintance from his university days with whom he had later become close friends and with whom he could have talked about his personal grief; but this friend was now Chief Education Officer in a remote part of the country. Of the people he knew in Petersburg the closest to him and the most likely were his private secretary and his doctor.

Mikhail Vasilyevich Slyudin, his private secretary, was a simple, intelligent, kindly and upright man, and Karenin felt that he was well disposed towards him personally; but their five years of official relationship had set up a barrier in the way of heart-to-heart talks.

Having finished signing some papers, Karenin remained silent for a long time, occasionally glancing up at Slyudin, and several times made an attempt to say something but could not bring himself to do so. He had a phrase all ready prepared: “Have you heard about my misfortune?” But he ended up by saying, as usual: “Then you’ll get this ready for me, won’t you?” and with that, let him go.

The other person was the doctor, who was also well disposed towards him; but a tacit agreement had long ago been reached between them that they were both overwhelmed with work, and both in a hurry.

Of his women friends, including the principal one, Countess Lidia Ivanovna, Karenin did not think at all. All women, simply as women, terrified and repelled him.

…

Karenin had forgotten about Countess Lidia Ivanovna, but she had not forgotten about him. At that most painful moment of lonely despair, she had come to see him and entered his study unannounced. She found him sitting with his head in his hands.

“J’ai forcé la consigne,” [“I’ve forced my way in”] she said, coming in with rapid steps and breathing heavily from emotion and her rapid movements. “I’ve heard all about it, Alexei Alexandrovich! My friend!” she continued, firmly pressing his hand in both of hers and looking with her lovely dreamy eyes into his.

Karenin got up with a frown and, freeing his hand from hers, gave her a chair.

“Won’t you sit down, Countess? I’m not receiving anyone today because I’m not well, Countess,” he said, and his lips quivered.

“My friend!” Countess Lidia repeated, without taking her eyes off him, and suddenly the inside corners of her eyebrows went up, forming a triangle on her forehead; her plain, sallow face became even plainer; but Karenin felt that she was sorry for him and on the verge of tears. He was overwhelmed with emotion; he seized her puffy hand and began kissing it.

“My friend!” she said, in a voice breaking with emotion. “You must not abandon yourself to grief. Your grief is great, but you must find consolation.”

“I am shattered, crushed, I’m no longer a human being!” said Karenin, letting go of her hand, but continuing to gaze into her eyes, which were full of tears. “What is so terrible about my situation is that nowhere, not even in myself, can I find any point of support.”

“You will find support, but don’t look for it in me, although I ask you to believe in my friendship,” she said with a sigh. “Our support is love, the love which He bequeathed to us. His yoke is light,” she said, with that ecstatic look which Karenin knew so well. “He will suport you and help you.”

Although these words were tinged with the Countess’s emotion at her own lofty feelings as well as with that ecstatic mystical attitude which had lately spread through Petersburg* and which, to Karenin, seemed excessive, he nevertheless was now pleased to hear them.

“I’m weak. I’m reduced to nothing. I did not foresee anything and, now, I don’t understand anything.”

“My friend,” repeated Countess Lidia.

“It’s not the loss of what now no longer exists, it’s not that,” Karenin went on. “I don’t regret that. But I can’t help feeling ashamed in front of people because of the situation I’m in now. It’s wrong, but I can’t help it, I can’t help it.”

“It was not you who accomplished that lofty act of forgiveness that I and everyone admires, but He who dwells in your heart,” said Countess Lidia, raising her eyes ecstatically, “and therefore you cannot be ashamed of your action.”

Karenin frowned and, bending back his hands, began making his fingers crack.

“One must know all the details,” he said, in a high-pitched voice. “There are limits to a man’s strength, Countess, and I’ve reached the limits of mine. The whole day today I’ve had to make arrangements, domestic arrangements arising” (he stressed the word arising) “from my new, solitary situation. The servants, the governess, the bills… These petty flames have burnt me up, I couldn’t stand it any longer. At dinner… yesterday I very nearly left the table. I couldn’t bear the way my son was looking at me. He didn’t ask me what was the meaning of it all, but he wanted to, and I couldn’t stand the look in his eyes. He was afraid to look at me, but that’s not all…”

Karenin was going to mention the bill which had been brought to him, but his voice shook and he fell silent. He could not recall that bill on blue paper for a hat and some ribbons without feeling sorry for himself.

“My friend, I understand,” said Countess Lidia. “I understand everything. It is not in me that you will find help and consolation but I have, all the same, come here only to help you if I can. If only I could relieve you of all these petty, humiliating cares… I understand that what is needed is a woman’s word, a woman’s authority. Will you entrust it to me?”

Karenin pressed her hand in silent gratitude.

“We’ll look after Seryozha together. I’m not very good at practical matters. But I’ll tackle it; I’ll be your housekeeper. Don’t thank me. I’m doing it myself…”

“I can’t but thank you.”

“But, my friend, you mustn’t surrender yourself to that feeling of which you were speaking – of being ashamed of what is, for a Christian, the very summit: ‘He that humbleth himself shall be exalted.’ And you cannot thank me. You must thank Him and ask Him for help. In Him alone shall we find tranquility, consolation, salvation, and love,” she said and, raising her eyes to heaven she began, so Karenin gathered from her silence, to pray.

Karenin listened to her now, and as he did so those phrases which had formerly seemed to him, if not unpleasant, at least superfluous now seemed natural and comforting. Karenin did not like this new, ecstatic spirit. He was a believer, interested in religion mainly from a political point of view; but the new teaching, which ventured certain new interpretations, he disliked on principle precisely because it opened the door to argument and analysis. In the past his attitude to this new teaching had been cold and even hostile and he had never argued with Countess Lidia, who was carried away by it, but had studiously evaded her challenges in silence. But now, for the first time, he listened to her words with pleasure and without any mental reservations.

“I’m very, very grateful to you both for your deeds and for your words,” he said, when she had finished praying.

Once again Countess Lidia pressed both her friend’s hands.

“Now I must set to work,” she said with a smile after a moment’s silence, and wiping the traces of tears from her face. “I’m going to Seryozha now. I shall only apply to you as a last resort.” And she got up and left the rom.

Countess Lidia went to Seryozha’s part of the house and there, spilling tears all over the frightened boy’s cheeks, she told him that his father was a saint and that his mother had died.

…

Countess Lidia fulfilled her promise. She really did take over all the cares of the arrangement and running of Karenin’s house. But she had not exaggerated when she had said that she was not good at practical matters. All her instructions had to be changed as they were impossible to carry out, and they were changed by Korney, Karenin’s valet, who was now, without anyone noticing it, running the whole of Karenin’s house and who, while helping his master to dress, would quietly and warily report to him what he thought he ought to know. But Countess Lidia’s help was, nevertheless, highly effective: she gave Karenin moral support by imparting to him the consciousness of her affection and respect and, more especially (so she comforted herself in her imagination), by almost converting him to Christianity – that is, she turned him from being an indifferent and lazy believer into an ardent and steadfast supporter of that new interpretation of Christian teaching which had latterly spread in Petersburg. It was not difficult to convince Karenin about this. Karenin, like Countess Lidia, and the other people who shared their point of view, was quite devoid of any depths of imagination, of that spiritual capacity thanks to which ideas provoked by imagination become so real that they demand conformity with other ideas and with reality. He saw nothing impossible or incongruous in the idea that death, which existed for unbelievers, did not exist for him and that, since he had complete faith (of the completeness of which he himself was the judge), there was no longer any sin in his soul and he was already experiencing full salvation here on earth.

It is true that Karenin was dimly aware that this faith was both shallow and erroneous and he knew that when, without thinking that his forgiveness was the act of a Higher Power, he had surrendered himself to the spontaneous emotion of forgiveness, he had experienced more happiness than when, as now, he thought constantly that Christ was living in his soul and that, when signing papers, he was fulfilling His Will. But it was essential for Karenin to think this; in his humiliation it was so essential for him to occupy that higher, if spurious, level from which he, despised by all, could despise others, that he clung to his imaginary salvation as if it really was salvation.

*The main agent of [this religious movement’s] spread through high society in St Petersburg was the third Baron Radstock (1833-1913), who preached a version of the doctrine of Salvation by Grace alone.

…

As a very young and ecstatically minded girl, Countess Lidia had been married off to a rich, aristocratic, very good-natured, jovial and profligate man. Not quite two months later, her husband had abandoned her, and responded to her rapturous assurances of affection merely with mockery and even animosity, which those who knew the Count’s kind heart and could see no shortcomings in the ecstatic Lidia were quite unable to explain. Since then, although they had not been divorced, they had lived apart and, whenever they did meet, her husband always treated her with unvarying and venomous mockery, the reason for which it was impossible to understand.

Countess Lidia had long ago ceased to be in love with her husband, but since then had never ceased being in love with someone or other. She would be in love with several people at the same time, both men and women; she would be in love with almost anyone who was in any way particularly distinguished. She was in love with all new princes and princesses who became connected by marriage with the Imperial family; she was in love with a Metropolitan, a bishop, and a parish priest. She was in love with a journalist, three Slavs and with Komisarov; with a cabinet minister, a doctor, an English missionary, and Karenin. All these loves, now waxing, now waning, did not prevent her from keeping up the most widespread and complex relationships at Court and in society. But ever since she had taken Karenin under her special protection after the misfortune which had befallen him, ever since she had been helping in his house, looking after his welfare, she had felt that none of her other loves were true loves and that now she was genuinely in love with Karenin only. The feeling which she now felt towards him seemed to her stronger than any previous feelings. Analysing that feeling and comparing it with those she had had before, she saw clearly that she would not have been in love with Komisarov if he had not saved the Emperor’s life, that she would not have been in love with Ristić-Kudžicki* if there had been no Slav question, but that she loved Karenin for himself, for his lofty, misunderstood soul, for the high-pitched sound of his voice with its drawling intonation which, to her, was sweet, for his tired gaze, for his character, for his soft white hands with swollen veins. She not only found joy in meeting him but she searched his face for signs of the impression she was making on him. She wanted to attract him not only by what she said but by her whole person. For him she now paid more attention to her clothes than she ever had before. She caught herself dreaming of what might have been, if she had not been married and if he had been free. She blushed from excitement when he entered the room and she could not restrain a smile of delight when he said something pleasant to her.

For the past few days Countess Lidia had been in a state of extreme agitation. She had learnt that Anna and Vronsky were in Petersburg. Karenin must be saved from meeting her, must be saved even from the agonizing knowledge that the dreadful woman was in the same town and that at any moment he might meet her.

Through her acquaintances Countess Lidia reconnoitred to find out what those abominable people, as she referred to Anna and Vronsky, were intending to do and, during those days, tried to direct all her friend’s movements so that he should not meet them. A friend of Vronsky’s, a young equerry through whom she had her information and who hoped, through the Countess, to obtain a concession, had told her that they had concluded their business and were leaving the next day. Countess Lidia was just beginning to breathe freely again when, the next morning, she was brought a note and was appalled to recognize the handwriting. The handwriting was Anna’s. The paper of which the envelope was made was as thick as parchment; the oblong yellow page bore a huge monogram, and the letter exuded a delicious smell.

“Who brought it?”

“A commissionaire from the hotel.”

For a long time, Countess Lidia was unable to sit down and read the letter. Her agitation brought on a fit of asthma, to which she was subject. When she had composed herself she read the following letter, which was written in French:

Madame la Comtesse,

The Christian sentiments which fill your heart give me what, I feel, is the unpardonable boldness of writing to you. I am unhappy at being parted from my son. I beg you to allow me to see him once before my departure. Forgive me for reminding you of myself. I am addressing myself to you, rather than to Alexei Alexandrovich only because I do not wish to make that magnanimous man suffer by reminding him of myself. Knowing your friendship for him, I feel you will understand me. Will you send Seryozha to me, or shall I come to the house at some prearranged time or will you let me know when and where I can see him away from the house? I do not anticipate a refusal, knowing the magnanimity of the person on whom it depends. You cannot imagine the yearning I have to see him, and therefore you cannot imagine the gratitude your assistance will awaken in me.

Anna

Everything in this letter irritated Countess Lidia: its contents, the allusion to magnanimity and, especially, its tone, which seemed to her too familiar.

“Say there’s no answer,” said the Countess, and then, opening her blotter, she immediately wrote a note to Karenin saying that she hoped to see him just before one o’clock at the Birthday Reception in the Palace.

“I must discuss an important and distressing matter with you. We can arrange there where to meet. It would be best of all at my house, where I will have your tea prepared for you. It is essential. He gives us a cross, but He gives us strength to bear it,” she added, so as to prepare him a little.

Countess Lidia usually wrote two or three notes a day to Karenin. She liked this means of communication with him, since it had elegance and mystery about it, elements lacking in her personal relations with him.

…

The reception was drawing to an end. Those who were leaving chatted as they met each other about the latest news of the day, newly acquired honours and changes in appointments for high officials.

“If we could only have Countess Marya Borisovna as Minister of War, and Princess Vatkovsky as Chief of Staff,” said a little white-haired old man in a gold-embroidered uniform, addressing a tall and beautiful lady-in-waiting, who had asked him about the changes.

“And me as a new equerry,” replied the lady-in-waiting, smiling.

“You have already been appointed – to the Ecclesiastical Department, with Karenin as your assistant.”

“How are you, Prince?” said the little old man, shaking the hand of a man who had just come up to him.

“What were you saying about Karenin?” said the Prince.

“He and Putyatov both got the Order of Alexander Nevsky.”

“I thought he’d already got it.”

“No. Just you look at him,” said the old man, pointing with his embroidered hat at Karenin who, wearing Court uniform with the red ribbon of his new order over his shoulder, was standing in the doorway of the hall with one of the influential members of the State Council. “He’s as pleased and merry as a cricket,” he added, breaking off to shake hands with a handsome, athletic Court Chamberlain.

“No,” said the Court Chamberlain, “he’s aged.”

“From worry. He’s drafting government projects all the time. He won’t let the wretched man go now until he has expounded it all point by point.”

“What d’you mean, he’s aged? Il fait des passions. [He makes people fall in love with him.] I think Countess Lidia must be jealous of his wife now.”

“Oh come! Please don’t say anything bad about Countess Lidia.”

“But is there anything bad about her being in love with Karenin?”

“Is it true that Mrs Karenin is here?”

“Well, she isn’t here in the Palace, but she is in Petersburg. I met her yesterday with Alexei Vronsky, bras dessus, bras dessous [arm in arm], in Morskaya Street.”

“C’est un homme qui n’a pas… [He’s a man who’s not…]” the Court Chamberlain began, but broke off to make way and bow to a member of the Imperial family who was passing.

So people went on talking incessantly about Karenin, blaming him and laughing at him, while he, barring the way to the member of the State Council whom he had cornered and never for a moment breaking off his exposition for fear of letting him escape, was expounding his financial project point by point.

At almost the same time that his wife had left him, an event had occurred in Karenin’s life which was the bitterest that could happen to a civil servant – his official advancement had come to a stop. It had come to a stop, and everyone clearly saw this, but Karenin himself did not yet realize that his career was over. Whether it was because of his clash with Stremov, or because of his misfortune with his wife, or simply because Karenin had reached the limit he was destined to reach, it had become obvious to everyone that year that his civil service career was over. He still occupied an important post, he was a member of many commissions and committees; but he was a man who had given all he had to give and from whom no one expected anything more. No matter what he said, no matter what he proposed, people listened to him as if what he was proposing had already been thought of long ago and was the very thing that was not needed.

But Karenin did not sense this and, on the contrary, being excluded from taking a direct part in government activities, he could now see, more clearly than before, shortcomings and mistakes in the activity of others, and considered it his duty to point out ways of correcting them. Soon after his separation from his wife he began to write a memorandum on the new legal procedure, the first of an innumerable number of useless memoranda which he was destined to write on all branches of administration.

Karenin not only failed to notice the hopelessness of his position in the administrative world – and was far from being distressed by it – but was more pleased with his activities than ever.

“He that is married careth for the things that are of the world, how he may please his wife… but he that is unmarried careth for the things that belong to the Lord, and how to please the Lord,” — says the Apostle Paul, and Karenin, now guided in all his affairs by the scriptures, often remembered this text. It seemed to him that ever since he had been left without a wife, he had been serving the Lord with these memoranda better than ever before.

The obvious impatience of the State Councillor who wanted to get away from him did not disturb Karenin; he stopped holding forth only when the State Councillor, seizing the opportunity when a member of the Imperial family went past, slipped away from him.

Left alone, Karenin bowed his head, collecting his thoughts, then looked round absentmindedly and went towards the door where he hoped to meet Countess Lidia.

“And how strong and healthy they all are physically,” thought Karenin, looking at a powerfully built Court Chamberlain with well-combed and scented side-whiskers and at the red neck, encased in uniform, of a prince, in front of whom he had to pass. “How truly it is said that everything in the world is evil,” he thought, giving another sidelong glance at the Court Chamberlain’s calves.

Walking unhurriedly, with his habitual air of weariness and dignity, Karenin bowed to these gentlemen who had been talking about him and looked at the door, trying to find Countess Lidia.

“Ah, Alexei Alexandrovich!” said the little old man, with a malevolent gleam in his eye, just as Karenin drew level with him and nodded coldly to him. “I have not congratulated you yet,” he said, indicating Karenin’s newly-acquired order.

“Thank you,” Karenin replied. “What a fine day it is today,” he added, particularly stressing, as was his habit, the word “fine”.

That they laughed at him, he knew; but he never expected anything from them but hostility; he was used to this by now.

Catching sight of Countess Lidia’s sallow shoulders arising out of her corset, and her lovely dreamy beckoning eyes, Karenin smiled, revealing his perfectly white teeth, and went up to her.

Countess Lidia’s dress had cost her a great deal of trouble, as had all her dresses of late. Her aim in dressing was now quite the opposite to the one she had pursued thirty years earlier. Then she had wanted somehow to dress herself up and the more the better. Now, on the contrary, she was obliged to adorn herself in a way so out of keeping with her years and figure that she was concerned only that the contrast between these adornments and her looks should not be too appalling. And, so far as Karenin was concerned, she had achieved this and she seemed to him to be attractive. For him she was the only island not only of kindly feeling but of love in the sea of hostility and mockery which surrounded him.

As he ran the gauntlet of mocking glances, he was drawn to her amorous gaze as naturally as a plant to the light.

“I congratulate you,” she said, indicating his order.

Restraining a smile of pleasure, he shrugged his shoulders and closed his eyes, as if to say that such a thing could not gladden him. Countess Lidia knew well that it was one of his principal joys, although he would never admit to it.

“How is our angel?” said Countess Lidia, referring to Seryozha.

“I cannot say that I am wholly satisfied with him,” said Karenin, raising his eyebrows and opening his eyes. “And Sitnikov is not satisfied with him either.” (Sitnikov was the teacher to whom Seryozha’s secular education had been entrusted.) “As I’ve said before, there is in him a certain coolness to those questions which are the most important of all and which should touch the heart of every man and every child,” began Karenin, explaining his ideas on the only subject, apart from his work, which interested him – his son’s education.

When Karenin, with the help of Countess Lidia, had returned once more to life and to work, he had felt it his duty to concern himself with the education of the son who had been left on his hands. Never before having been concerned with questions of education, Karenin had devoted some time to a theoretical study of the subject. And having read several books on anthropology, pedagogy and didactics, Karenin had drawn up for himself a plan of education and, having invited the best educationalist in Petersburg to supervise it, he had set to work. And this work kept him constantly occupied.

“Yes, but what about his heart? I see in him his father’s heart and with such a heart the child can’t be bad,” said Countess Lidia with rapture.

“Yes, perhaps… So as far as I am concerned, I am fulfilling my duty. That is all I can do.”

“Come to my house,” said Countess Lidia, after a moment’s silence, “we must have a talk about what is, for you, a sad business. I would give anything to spare you certain memories, but others do not think in the same way. I have received a letter from her. She is here, in Petersburg.”

Karenin winced at the mention of his wife, but immediately his face assumed that absolute immobility which expressed his complete helplessness in this matter.

“I expected it,” he said.

Countess Lidia looked at him rapturously and her eyes filled with tears of admiration at the loftiness of his soul.

. . .

When Karenin entered Countess Lidia’s cosy little study, decorated with old china and hung with portraits, the lady of the house was not yet there. She was changing her dress.

The round table was covered with a cloth, and on it stood a Chinese tea service and a silver kettle with a spirit lamp. Karenin looked round absentmindedly at the innumerable and familiar portraits which decorated the study and, sitting down at the table, opened the New Testament which was lying on it. The rustle of the Countess’s silk dress diverted his attention.

“Well, now we can sit down peacefully,” said Countess Lidia with an uneasy smile, squeezing herself in between the table and the sofa, “and have a talk over our tea.”

After a few words of preparation Countess Lidia, breathing heavily and blushing, handed over the letter which she had received to Karenin.

When he had read the letter he remained silent for a long time.

“I don’t suppose I have the right to refuse her,” he said timidly, looking up.

“My friend! You don’t see evil in anyone!”

“On the contrary, I see that everything is evil. But is this right?...”

His face expressed indecision and a search for advice, support and guidance in a matter which was, to him, incomprehensible.

“No,” interrupted the Countess, “there’s a limit to everything. I understand immorality,” she said, not quite sincerely since she had never been able to understand what led women to immorality, “but cruelty I don’t understand, and cruelty to whom? To you! How can she stay in the same town as you? Oh yes, ‘live and learn’. And I am learning to understand your high-mindedness and her low character.”

“But who will throw a stone?” said Karenin, obviously pleased with the part he was playing. “I have forgiven everything, and therefore cannot deprive her of what her love – her love for her son – needs…”

“But is that love, my friend? Is it sincere? Suppose you have forgiven, that you do forgive… But have we the right to treat our angel’s heart like that? He thinks she is dead. He prays for her and asks God to forgive her her sins… And it’s better that way. Otherwise what will he think?”

“I hadn’t thought of that,” said Karenin, evidently agreeing.

Countess Lidia covered her face with her hands and was silent for a moment. She was praying.

“If you ask my advice,” she said, having finished praying, and uncovering her face, “I don’t advise you to do this. As if I did not see how you are suffering, how this has opened up your wounds! But suppose that you, as always, forget about yourself. What, then, can this lead to? To fresh suffering on your side, to torment for the child? If she has any human feeling left in her, she should not want this herself. No, I have no hesitation in advising against it and, if you allow me, I will write to her.”

And Karenin agreed, and Countess Lidia wrote the following letter in French:

Madame,

To remind your son of you might lead to questions on his part to which it would be impossible to reply without inducing in the child’s heart a spirit of condemnation of what should, for him, be sacred; and I therefore ask you to accept your husband’s refusal in a spirit of Christian charity. I pray to the Most High to have mercy on you.

Countess Lidia.

This letter achieved the hidden aim which Countess Lidia had not even admitted to herself. It offended Anna to the very depths of her soul.

Karenin, too, returning home from Countess Lidia, was unable that day to devote himself to his usual occupations or to find the spiritual peace of mind, which he had felt before, of a believer who had found Salvation.

The memory of his wife who was so guilty towards him, and to whom he had been so saintly, as Countess Lidia used so justly to tell him, should not have disturbed him; but he was not easy in his mind: he could not understand the book he was reading, could not drive away agonizing memories of his relations with her, of those mistakes which, it now seemed to him, he had committed in regard to her. The recollection of how he had received her confession of infidelity, on the way back from the races (and, in particular, of his insistence that she should keep up merely the outward appearances, and of his failure to challenge Vronsky to a duel), tormented him like remorse. The memory of the letter which he had written her also tormented him; in particular, his forgiveness, which no one wanted, and his care for another man’s child seared his heart with shame and remorse.

And he now experienced an exactly similar feeling of shame and remorse, as he went over his past with her in his mind and recalled the clumsy words with which, after long hesitation, he had proposed to her.

“But how am I to blame?” he kept saying to himself. And this question always evoked another question: did those other people, those Vronskys, those Oblonskys… those Court Chamberlains with fat calves, did they feel differently, did they love differently, did they marry differently? And he visualized a whole row of these vigorous, strong, self-confident people, who always and everywhere automatically attracted his inquisitive attention. He tried to drive away these thoughts, tried to convince himself that he was not living for this transient life but for life eternal, and that he had peace and love in his soul. But the fact that in this transient, insignificant life he had committed, so it seemed to him, a few trivial mistakes, tormented him as if the eternal life in which he believed did not exist. But this temptation did not last long and, soon, the serenity and high-mindedness, thanks to which he was able to forget what he did not want to remember, were restored to his heart.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1QcB6O4Uytg

p. 666-673 (Pt. 7, Ch. 20-22):

Princess Betsy Tverskoy and Oblonsky had long been on a very odd footing with each other. Oblonsky always flirted with her in a bantering way and told her, also in joke, the most improper things, knowing that that was what she liked most. The day after his conversation with Karenin, Oblonsky went to see her and felt himself so young that in this bantering talk and flirtation got carried away beyond the limits within which he knew how to extricate himself as, unfortunately, he found her not only unattractive but actually repulsive. But initially this bantering relationship between them had been established because she found him very attractive. He was, therefore, very glad when Princess Myakhky came and put an end to their tête-à-tête.

“Ah, you’re here, too,” she said when she saw him. “Well, and how’s your poor sister? Don’t you look at me like that,” she added. “Ever since everyone’s started attacking her – and they’re all a hundred thousand times worse than she is – I’ve thought she did a very fine thing. I can’t forgive Vronsky for not letting me know when she was in Petersburg. I would have called on her and would have taken her everywhere with me. Please give her my love. Now tell me all about her.”

“Oh indeed, her situation is very difficult, she…” began Oblonsky who, in the simplicity of his heart, mistook Princess Myakhky’s words for sterling coin!

“Tell me all about your sister.” Princess Myakhky immediately interrupted him, as she generally did, and started speaking herself. “She did what everyone does except me – only they hide it but she did not want to deceive anyone and did a very fine thing. And did even better by throwing up that half-witted brother-in-law of yours. You must forgive me. Everybody said he was so clever, so clever, only I said he was a fool. Now that he’s struck up that friendship with Countess Lidia and Landau they all say he is half-witted, and I would be glad not to agree with them all, but this time I can’t.”

“Do explain, please,” said Oblonsky, “what does it all mean? I saw him yesterday in connection with my sister and asked for a definite answer. He did not give me an answer, but said he would think it over, and this morning instead of an answer I got an invitation from Countess Lidia for this evening.”

“Ah, there you are!” said Princess Myakhky with glee. “They’ll ask Landau what he thinks.”

“What do you mean – Landau? Who’s Landau?”

“What? You don’t know Jules Landau, ‘le fameux Jules Landau, le clairvoyant’ [the famous Jules Landau, the clairvoyant]? He is another half-wit, but on him depends your sister’s fate. That’s what comes of living in the provinces, you don’t know anything. Landau, you see, was a ‘commis’ [shop assistant] in Paris, and went to see a doctor. In the doctor’s waiting room he fell asleep and in his sleep started to give advice to all the patients. And remarkable advice it was. Then Yury’s wife – you know, that man who is always an invalid? – heard about that fellow Landau and brought him to see her husband. He is treating him now. And hasn’t done him any good, I consider, because he is just as weak as ever, but they believe in him and take him with them everywhere. And they’ve brought him to Russia. Here he has become all the rage and has taken to treating everyone. He’s cured Countess Bezzubov and she became so fond of him that she adopted him.”

“How do you mean – adopted him?”

“She just did. He’s not Landau any longer, but Count Bezzubov. But this is not the point, but Lidia – I love her dearly but she hasn’t got her head screwed on in the right place – is naturally all over Landau now and neither she nor Karenin take any decisions without him and, therefore your sister’s fate is now in the hands of that man Landau, alias Count Bezzubov.”

…

After an excellent lunch and a great quantity of cognac at Bartnyansky’s, Oblonsky arrived at Countess Lidia’s only slightly later than the time appointed.

“Who else is here? The Frenchman?” Oblonsky asked the porter, looking at Karenin’s familiar coat and an odd, rather artless-looking coat with clasps.

“Alexei Alexandrovich Karenin and Count Bezzubov,” replied the porter sternly.

“Princess Myakhky has guessed right,” thought Oblonsky as he went up the stairs. “Strange! However, it might be as well to get on friendly terms with her. She has enormous influence. If she drops a hint to Pomorsky, the thing’s in the bag.”

It was still quite light outside, but in Countess Lidia’s little drawing room the blinds were drawn and the lamps lit.

At a round table, under a lamp sat the Countess and Alexei Alexandrovich discussing something in low tones. A shortish, lean man with hips like a woman’s, knock-kneed, very pale, handsome, with beautiful shining eyes and long hair that fell over the collar of his frock coat, stood at the other end of the room, examining portraits on the wall. After greeting his hostess and Karenin, Oblonsky could not help casting another glance at the stranger.

“Monsieur Landau,” said the Countess, turning to him with a gentleness and caution that impressed Oblonsky.

Landau hastily looked round, came up with a smile and put a clammy, flaccid hand into the hand that Oblonsky stretched out to greet him, and then immediately went back to look at the portraits.

“I am very glad to see you, particularly today,” said Countess Lidia, motioning Oblonsky to a seat next to Karenin.

“I’ve introduced him to you as Landau,” she said in a low voice, glancing at the Frenchman and then back to Karenin, “but he is really Count Bezzubov, as you probably know. Only he doesn’t like the title.”

“Yes, I have heard,” replied Oblonsky. “They say he completely cured Countess Bezzubov.”

“She came to see me today, she is so pathetic!” said the Countess, turning to Karenin. “For her this separation is terrible. It’s such a blow for her.”

“And he is definitely going?” asked Karenin.

“Yes, he is going to Paris. He heard a voice yesterday,” said Countess Lidia, looking at Oblonsky.

“Ah, a voice!” repeated Oblonsky, feeling that he had to be as circumspect as possible in that company where something special, to which he had as yet no key, was either happening or about to happen.

There was a minute’s silence, after which Countess Lidia said to Oblonsky with a subtle smile, as if about to broach the main topic of conversation:

“I have known you for a long time and am delighted at this opportunity of getting to know you better. ‘Les amis de nos amis sont nos amis’ [‘Our friend’s friends are our friends’]. But to be a friend one must try to understand one’s friend’s spiritual state, and I’m afraid you are not doing this in the case of Alexei Alexandrovich. You understand what I mean,” she said raising her beautiful, dreamy eyes.

“In a way, Countess, I realize that the position of Alexei Alexandrovich…” said Oblonsky who did not quite understand what it was all about and was therefore keen to keep to generalities.

“The change is not in the external circumstances,” said Countess Lidia sternly, while her love-sick eyes followed Karenin who had got up and gone across to Landau, “his heart has changed, he has been given a new heart and I am afraid you have not sufficiently tried to understand the change that has occurred within him.”

“Well, in a general sort of way I can imagine the change. We have always been friendly, and now…” said Oblonsky, responding with a tender glance to the glance of Countess Lidia, and considering which of the two ministers she was more friendly with, so as to know which of the two he would have to ask her to use her influence on.

“The change that has taken place in him cannot weaken his feeling of love for his neighbour; on the contrary, the change that has taken place in him must strengthen this love. But I’m afraid you don’t follow me. Would you like some tea,” she said indicating with her eyes a servant who was handing tea round on a tray.

“Not entirely, Countess. Naturally, his misfortune…”

“Yes, a misfortune which became the highest happiness, when his heart was made new and was filled with Him,” she said casting love-sick glances at Karenin.

“I daresay I can ask her to speak to both of them,” thought Oblonsky.

“Oh certainly, Countess,” he said, “but I should imagine these changes are so intimate that no one, not even the closest of friends, likes to talk about it.”

“On the contrary, we must talk about these things and help each other.”