View Poll Results: Ahlam Mosteghanemi

- Voters

- 0. You may not vote on this poll

-

Alpha

-

Beta

-

Gamma

-

Delta

-

ILE (ENTp)

-

SEI (ISFp)

-

ESE (ESFj)

-

LII (INTj)

-

EIE (ENFj)

-

LSI (ISTj)

-

SLE (ESTp)

-

IEI (INFp)

-

SEE (ESFp)

-

ILI (INTp)

-

LIE (ENTj)

-

ESI (ISFj)

-

LSE (ESTj)

-

EII (INFj)

-

IEE (ENFp)

-

SLI (ISTp)

-

WE'RE ALL GOING HOME

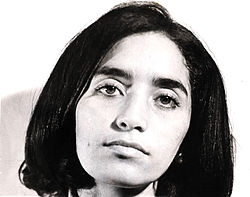

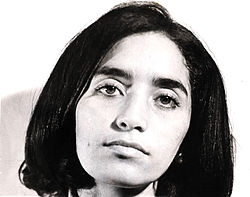

Ahlam Mosteghanemi

Ahlam Mosteghanemi

EIE or IEI-Fe

Chaos of the Senses / Ahlam Mosteghanemi (translated by Baria Ahmar); p. 86-90

Was this love? Only one word from him, and I was another woman who bore no resemblance to the one who had left the house wearing such a simple dress, with no manicure and exhausted features. I returned home a prettier woman, and life itself seemed more beautiful and enticing. Even more lovely was the fact of life’s surprises. It can change at every street corner. An accident can befall you, and you can meet a man who sends tremors through your body.

At home, I found Farida glued to the television, as if she didn’t spend her life in front of it watching the same silly soap operas, and as if it were not waiting for her back in Constantine. I felt pity for her stupidity. How could I explain to her that a human being should live, filling up his senses, his lungs, and emotions with everything that he encounters along the way and that could never be repeated. How could I convince her to love things she would only see once, not what she watched on television every day?

I felt a desire to pass on to her my happiness and my passion for life, but she was a woman with limited dreams and limited intelligence. I found a blessing in her naivete, however; at least she wouldn’t pay any attention to what was happening to me.

She took her eyes away from the television screen only to ask if I had thought to bring any bread. I answered her with a groan. I had forgotten it at the bakery.

As I headed toward my bedroom to change, I thought to myself that I had officially entered the phase of sweet nothings. If I had forgotten the cakes I had spent half an hour choosing, I could be expected to forget other things as well, and to live in another universe that had nothing to do with the details of my earthly planet.

As soon as I had changed clothes, I carried my newspapers and headed toward the garden. I had no intention of reading, but I wanted to be by myself to go through my own story with that man whom I had breathlessly hunted through the streets of Constantine. When I had lost all hope and left town, I found that he had beaten me here.

Life is strange with its contrary logic. You run after things breathlessly, and they run away from you. Then, no sooner do you sit down and convince yourself that they are not worth that running around, they come running to you. So you don’t know whether to turn your back or open your arms to receive that gift the heavens sent down to you. It may contain your happiness, or your end. Thus, one should never forget that lovely saying of Oscar Wilde’s: “There are only two disasters [or tragedies] in life: one is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it.”

I wondered which of the two disasters this man was. What if he had returned to be my second disaster after being the first?

I inspected the newspaper where he had written his telephone number with a pencil, and from it, I tried to predict my destiny with him. All those zeros scared me, but the rest of the numbers reassured me. I love numbers that can be divided by three; I feel that they resemble me. But I didn’t stop myself from wondering why he wrote it with a pencil. Was it because artists usually wrote with pencils? Or, because for him, things stood to be erased at any moment? Or, because it was the era of lead pencils, which write one story and erase another. The proof was that his phone number was written on the small white margin on the front page of a newspaper, filled with the news of national and regional disasters.

Why did his love come with national tragedies? It seemed as if there were no space left for love in our lives, except that almost invisible space on the pages of our days. Wasn’t there any room left for a happy and natural love in this country?

Joy lived in me, while the papers of sadness lurked on that garden table. Even before flipping through them, I had already regretted having brought them there. I recalled a friend’s saying: “I’ve never bought an Arabic newspaper that I didn’t regret buying.”

I hurriedly turned the pages, afraid that the news would change my mood. But a few headlines caught my attention and tempted me, with a masochistic desire, into reading them.

Buying an Arabic newspaper, in June 1991, to read about the fortune of this nation is to subject oneself to a heart attack. Buying an Algerian newspaper of the same date is to risk losing your mind, as you see all the local and national crises publicized on the front page.

Before you open the paper, the nation attacks you with headlines: “The military authorities have suspended the curfew until after the Adha Feast”; “Over the last three days, 469 people arrested”; “The Deliverance Front declares civil disobedience and announces the beginning of a public strike”; “Heavy security personnel presence around state buildings and mosques”; “Public buses taken over in preparation for a huge march on the capital.”

Fleeing to the bottom of the page, you find other countries awaiting you, nations you thought were yours as well. At least, that’s what you’ve been told since your childhood, by a very naïve poet who died singing, “The land of the Arabs is my home.” But he was no longer there to read with you the headlines of an Arab newspaper on June 15, 1991: “The Lebanese army continues to hold siege at the Palestinian camps of Ain al-Hilweh and al-Mayya wa Mayya”; “Dozens of Egyptians arrested and tortured by Iraqi authorities”; “Executions of Arabs continue in Kuwait”; “American companies take on the reconstruction of Kuwait”; “Egyptian debts canceled.”

The good news in all this is not the following and last item, but a story found inside it, written in bold letters: “The Algerian meat authority imports 220,000 sheep from Australia on the occasion of the Adha Feast; most arrived safely.”

‘Safely’ only in that they are still alive, despite having spent a month at sea piled up in a steamer; most only awaiting the mercy of being slaughtered for the feast. Like the Algerians who are piled up by the dozens at the door of the Australian embassy, waiting for months for the mercy of a visa to a country that is supposedly looking for workers.

On the occasion of the arrival of the ship carrying the blessed load of sheep, the newspaper set aside one full page to debate the religious question raised by the amputated tails of Australian sheep, quite unlike the fat tails that Algerians are used to. The question of whether it was permissible to sacrifice them ended with the following fatwa: “Amputating the tail, all or in part, by the amount of two-thirds is considered a flaw in the sacrificial animal, whether the tail is entirely amputated or only partially so before or after it is born.”

The next question, then, was what to do with all those sheep. What would be sacrificed for the feast?

In fact, the real problem was not in the tails of the Australian sheep, which occupied both laymen and religious scholars for days. Rather, it was in those ‘human sheep’ piled up in front of the Australian embassy. The question was big and scary. How did we—once a nation that exported revolution and dreams to the world—come to export human beings and import sheep?

p. 72-6

Nasser hadn’t yet recovered from the Gulf War. When the Iraqi invasion started, he lived in anxiety, pulled in all directions. He would go to sleep a supporter of Saddam Hussein and wake up defending Kuwait. But as soon as the conflict turned into a military confrontation with an international alliance against Iraq, he swung irrevocably back to the Iraqi side, taken by the mother of all battles. Like most, he was betting on the impossible, dreaming of a greater battle in which he would liberate Palestine.

When the first Iraqi missiles fired at Israel hit barren land, he called me that night.

“Was that the Scud missile Saddam has been threatening the world with? It was nothing but a suppository shoved in Israel’s backside.”

I chuckled. I never expected that war to have such a big impact on Nasser.

That was the only period when Nasser used to come to see me, perhaps just to transfer his anger and blame to someone else and nothing more. He knew that he could pass on to me things of that kind. One day he came to see me and found me with my papers, when we were in the middle of disaster. What insults followed! He started rebuking me, as if I was myself hurting someone.

“I don’t understand how you’re able to continue writing as if nothing has happened! Neither this earth moving under your feet, nor the destruction awaiting an entire nation can keep you from writing. Stop and look at the ruins around you. What you’re writing makes no difference.”

“But I’m a writer,” I answered, as if apologizing.

He yelled at me.

“That’s exactly why you should shut up, or kill yourself. In a few short weeks, we’ve gone from being a nation that possessed a nuclear arsenal to one that barely has a few knives! And you’re writing. We’ve gone from being a nation with the biggest financial reserves in the world to a few tribes begging from international assemblies, and you write. The ones you’re writing for are waiting for handouts of bread and medicine. They can’t afford to buy a book. Everyone else is dead, even the living are dead, so keep quiet out of respect for them!”

I don’t think that Nasser knew that with these words, which he might have later reconsidered, he had changed the course of my writing, forcing me into a two-year silence. For two entire years, I learned to despise all those writers in newspapers and magazines, who continued to live shamelessly, in the face of the dead body of Arabism.

I watched American television channels compete to show ‘live’ the death of an Arab army whose men wandered in the desert starving. They dropped like flies over dozens of kilometers into the ditches of disgrace sprayed with the bombs of an absurd death, not knowing why it was happening to them. I saw the convoys of the miserable, fleeing in trucks from one Arab country to another, leaving everything behind after a lifetime of misery, and still not understanding why.

I saw Kuwaitis dancing in the streets, carrying American flags. They kissed pictures of President Bush and offered General Schwarzkopf handfuls of Kuwaiti soil. I failed to comprehend how we Arabs could ever have reached such a point.

Only one man, indifferent toward us, never lost anyone dear to him in any of the wars we had improvised, nor did he lose weight in times of famine. He would appear on television swimming, while we drowned, and would promise us more victories.

Committing suicide was always on my mind during that period. The only thing that kept me from doing it was the grief my mother would feel by my death.

I was looking, in fact, for a spectacular death, not at all like that humble shotgun that Khalil Hawi used to put a bullet in his forehead on June 7, 1982, in protest against the Israeli invasion of Lebanon before the eyes of all Arabs.

“Where is this nation? I am ashamed to say I’m an Arab when they stand by watching disgracefully,” he said to his friends before pulling the trigger.

I wanted a suicide that would equal my grief to that of the Japanese writer, Mishima. After delivering the fourth and final part of his novel to the printer, he headed one Sunday morning to execute the final chapter of his life the way he had planned it. He had decided to commit suicide in protest of Japan’s humiliating exit from World War II before the Americans, and the loss of his national identity in the face of the western invasion.

He prepared for his death beautifully by taking private lessons in wrestling, horsemanship, and bodybuilding, which enabled him to take the Japanese army commander hostage, and address a rousing speech to one thousand Japanese soldiers who were gathered for a national occasion. When his speech had no effect on that defeated army, Mishima went back to the army commander’s room and put on the traditional Japanese garment, tying the sash and buttoning the buttons with noticeable self-composure. Then, he invited the photographers to take pictures of him and his small army of one hundred young men, whom he had prepared to die in defense of Japan’s greatness. He had stood before the photographers’ lenses, holding his banned Samurai sword, while he and his followers committed hara-kiri one after the other.

Farewell, Mishima!

Wherever you are, my friend, I kiss the forehead of your decapitated head, thrown in November 1970 at your nation’s feet, as an eternal rejection of the humiliating submission to America.

I still wonder, were we optimistic or naïve to have aligned ourselves with a nation so stubborn in its defeat that it committed all those failures?

During that period, seeing Nasser became a daily necessity for me to keep my Arabism alive, outdoing me in everything and refusing to let me curse one particular Arab regime. I could either curse them one by one for defined and convincing reasons or I could keep silent. To him, cursing one regime and not another was a bigger crime than being silent about it.

I remember how he used to drop by and spend some time with me.

“May God help this nation,” he would say as he departed. “Half our rulers are traitors and the other half are lunatics. The most dangerous, of course, are the lunatic traitors.”

Then, suddenly Nasser changed.

He stopped speaking about the 26 billion that had evaporated from the Algerian state treasury, and about his friends who had enlisted along with thousands of other young Constantinian students, preparing themselves to defend Iraq and die under its flag. Incidentally, the words “God is great” had been added to that flag, causing some skeptics to suggest a slogan be added to the Algerian flag: “God is the victor,” meaning we certainly couldn’t do anything for them.

Nasser also stopped talking about rumors, which everyone believed, that Israel had obtained missiles that could reach Algeria and was preparing to hit Constantine. These rumors kept people in a state of alert for over a month, as if they hoped it would happen for the pleasure of jihad or the passion for martyrdom.

Was it he who had lost all desire to talk, or I who had lost my enthusiasm for all those causes, while reaching a state of stupefaction?

Between his national disappointments and the bankruptcy of his nationalist dreams, he washed his hands of Arabism, or, more correctly, he performed his ablutions to find a new cause in fundamentalism. I, who had always lived one cause behind him, was unable to understand exactly what was happening to him. How, between one meeting and another, did he grow so distant, becoming such a stranger to me?

I no longer dared to laugh with him or tell jokes like I used to. I did not even dare to contradict him, afraid it would provoke an argumentative discussion based on a logic for which I had no answers.

p. 19-20

I love that moment when a man surprises me, even if after that he’s not as I imagined. Every drama with a man anchors you at the port of surprise. If that man is a husband, the story will undoubtedly take you through a series of surprises. In the beginning, we know the person we have married, but as the marriage goes on we no longer know with whom we live.

The most mysterious and surprising thing is the generation of men who belong to the era of long-term wars that ruthlessly swallowed their childhood and teenage years, and turned them into violent, yet fragile men, sensitive and tyrannical at the same time. These men always conceal inside of them another man, and no one knows when he will awaken. It is either that or they behave like the children they never were. They invented the game of Lego so that, like all children, they could practice putting its pieces together according to their childish whims, and then take them apart again.

My husband was born with a military temperament, I suppose, — for him to unintentionally break my spirit, exactly the same way he seduced and broke me years before, with no effort? Isn’t power like wealth, making us seem more beautiful and more desirable? Aren’t women like nations, always falling prey to the charm of the military uniform and its authority, before they realize that its power stems from their own awe of it?

I admit he did it gradually, with much elegance, and perhaps with much planning. I was willingly led toward my own enslavement, most probably unaware of it. Happy with my serenity and confidence in him, I left to him the better role, that of the man who gives orders, decides and demands, protects and pays, and even goes too far.

I found in his behavior something of the father-like authority I had been deprived of, while he found in such authority a continuation of his duties outside the home.

I remember that our relationship started with mutual awe, and with the violence of a hidden challenge. I should have known that violent relationships are the shortest because of their ferociousness and that we could not invest everything in one relationship; we couldn’t be a married couple, friends, fathers, lovers, and national symbols.

As for him, he probably thought like a military man in this matter, too. When one of them reaches a position of power, he insists on occupying all the key positions in the state and all the important ministries, thinking that no one else is worthy of occupying them. Indeed, the presence of another person is a permanent threat to him. That was why he didn’t leave a free space in my life where anyone could sneak in. He took over all the seats without being qualified for any of them.

Later on, I realized that his fatherliness meant the most to me, and that the prestige of his military rank and political position only mattered to me insofar as it kept alive the memory of struggle I had grown up with, and the pride of an Algeria I dreamed of. I used to see my country in his stature, in his strength and loftiness. In his body that had experienced fear, cold, and starvation during the long years of liberation, I saw what justified my desire, and for the sake of memory I honored it.

A long time went by before I realized how foolish it was of me to mix up the complexity of the past with the opposite reality. It was exactly the way I now mixed the illusion of writing with life and insisted on going to that illusory meeting, which I had tried in vain to convince myself didn’t concern me and would take place between characters of ink that would never leave the world of paper.

Nevertheless, I would go, not realizing that writing, as my refuge from real life, was drawing me in a roundabout way toward it, throwing me into a drama that would become, page after page, my own story.

p. 41-43

“It’s strange, our relationship that began in the dark. Since then, I’ve wanted to bring some light to the story.”

“But we didn’t meet in the dark,” he said smiling.

I almost asked him where we did meet, but the question seemed strange and might reveal me, if he really believed me to be her. I tried to lure him into a confession.

“I love the stories behind romantic encounters. In every encounter between a man and a woman, there is a miracle, something beyond them that brings them together at the same time and place to step into the path of the same tornado. That’s why lovers always remain dazed by the impact of their first encounter, even after they’ve split up. It’s a kind of ecstasy that can’t be recaptured, because it’s the only pure thing that is preserved from the destruction love leaves in its wake.”

I expected him to say something related to an encounter or a story.

“The beginning of all love stories is beautiful, but the most beautiful was ours.”

“Truly?”

“Of course, because it is a miracle that happens every time.”

He said only that sentence, which allowed me to deduce that we had met before that movie, but where and when? It didn’t appear that he was ready to answer these questions; he plunged again into a fit of silence, filling in between us phrases of foggy smoke. I watched him for a moment, as he was distracted from me, by us or by her, then I broke the silence with the first sentence that crossed my mind.

“A man who wears black places a certain distance between himself and others. That’s why there are some questions—simple as they are—that I don’t dare to ask you. You look like a man who despises questions.”

He interruped me as if amazed.

“I despise questions? Who says so?” I thought then that I had made a mistake, but he went on. “I like the great questions, the scary ones that have no answers. As for the curious questions, their naivete annoys me, and I think that they bother other people as well.”

“So how do you deal with questions from people around you?”

He took a deep drag on his cigarette, as if he hadn’t expected my question, and answered with a voice that was not free of scorn.

“People? They usually ask only stupid questions, forcing you to reply with equally stupid answers. For instance, they ask you what you do, not what you would have liked to do. They ask you what you own, not what you’ve lost. They ask about the woman you married, not about the one you love. About your name, but not if it suits you. They ask your age, but not how well you’ve lived those years. They ask about the city you live in, not about the city that lives in us. And they ask if you pray, not if you fear God.

“So I’ve gotten used to answering these questions with silence. You know, when we shut up, we force others to reconsider their mistakes.”

[How] mind-boggling this man was, with his eloquent words, as confusing as his silence; his complicated yet simple way of reasoning was with answers that only led to further questions. Though he didn’t leave me any space to ask a basic question, I discovered in the rules of his logic a legitimate way to coerce him and lead him to speak a truth that could only be drawn out of him backward.

I faced him with some cynicism.

“You are a man seduced by inverse questions. Do you have enough courage to answer my questions?”

“It depends on your intelligence,” he challenged jokingly.

I rose to the challenge and tossed out my first question.

“What is the name you wished to carry?”

“The name you’ve chosen for me in your book fits me well.”

He was laughing as he answered me, and I couldn’t believe my ears. His answer meant that he knew who I was! But who was he to address me as if he had just stepped out of my story?

“But I haven’t chosen a name for you yet,” I answered as if joking.

“So be it. It suits me perfectly to remain nameless,” he replied with the same sort of irony.

p. 66

Writing always draws fear, because it appoints [or confronts] us with all those things we are afraid to face otherwise, or to examine deeply.

p. 152-182

Why had he turned the world into a few words of the absolute, and love into words of division? With such words, it was difficult for any woman to keep up with him or defeat him.

I was the one who had engaged him in a linguistic battle, a mistress of words who refused to be beaten by her hero on her own ground. But there I was, losing to him round after round, getting more entangled question after question, with each one leading to another.

I knew from the beginning that questions were a romantic involvement, but I didn’t know that with this man answers produced their own predicament. I loved his answers, although I confess that often I didn’t understand exactly what he meant. I loved everything he said, perhaps because I was taken by the vagueness of his words.

I caressed his hand.

“I love you. Set me free me from my bonds of slavery.”

He pulled me to him and held me.

“Love means allowing the other to subdue and defeat you, making away with everything that you are. It’s okay to be defeated for a while . . . love is a state of weakness, not strength.”

“But . . .”

“But, because you don’t realize that, you’re repeating the same mistake you made in a previous book.”

I wanted to ask him when and in which book, but his lips stole my questions and carried me to a sudden kiss, just like his answers. I surrendered to the invasion of his lips, as though I wanted to prove to him with every inch of my body that fell under his masculinity how much I loved him.

In truth, I had neither the power nor the desire to resist him. I found pleasure in my own astonishment of him, as I watched him open the secret locks of my body. Pleasure has a password and a physical cipher that enslaves you to another without even realizing it. This man, who had only used his lips—which had given him directions to my pleasure, allowing him to tread those secret paths of desire that no man’s lips had ever crossed before. [(or) This man, who had only used his lips — what/who had given him directions to my pleasure, allowing him to tread those secret paths of desire that no man’s lips had ever crossed before?]

He suddenly planted two quick kisses on my lips, like periods at the end of a sentence, and got up to look for his cigarettes.

I took the opportunity to freshen up in the bathroom. Without interest, I examined his manly accouterments. The thing that stopped me was two bottles of that cologne on a shelf, one of them opened and the other one still wrapped in plastic. I pulled down the open bottle and looked at it with the curiosity of someone who has stumbled upon a secret. I remembered all those times I had almost asked him the name of his cologne. And I remembered that my story with this man had begun because of a word and a scent, perhaps because of that very cologne. Without it, I wouldn’t have recognized him.

I was still holding the bottle when he passed by in the hall on the way to the kitchen.

“Is it because I told you I liked your cologne that you started buying two bottles at once?” I asked him while trying the cologne on the palm of my hand.

He laughed.

“No. I bought them in France. Every time I travel I bring one for me and one for my friend Abd al-Haqq. Actually, he’s the one who introduced to me to it. He doesn’t use anything else.”

I was about to leave the bathroom when he came back, as if he had remembered something.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t bring you anything. I came back in such a hurry. Do you mind if I offer you this bottle of cologne? They say that women like to wear the cologne of the man they love. Put some on whenever you miss me,” he said as he handed me the bottle.

I took it from him.

“I didn’t think of that, but it seems like a good idea. If it’s about missing you, I’m afraid I’ll need a bottle every week! But what about your friend?”

“Don’t worry. I’ll take care of him.”

That gift made me very happy. I felt like I was growing closer to him every time we met, sneaking into his intimate world where he least expected it and stealing whatever could lead me to him.

I went back to the living room where he was sitting and smoking on the couch opposite me. It was as if he had decided to watch me or see what he had done to me in the space of a kiss. I put the bottle in my handbag with the same joy I had felt that day I had taken that book by Henri Michou. I might finally discover who he was.

“Do you know what the most beautiful gift you could give me is?”

He continued to smoke, putting his feet up on the table.

“What?”

“The truth. Can you give me the truth? I have the right to know who you are.”

“Postpone your disappointment a bit,” he answered sarcastically.

But I insisted. “What’s your name? Is it so difficult for you to tell me your name?”

He laughed. “No, but which one do you want to know?”

“You have two names? Why?”

“Because we live in a time when even nations and regimes and parties have changed their names in a few short years with the stroke of a pen, in what is essentially a moment in history. In Russia alone, twenty-eight cities have changed their names, including Leningrad. So why can’t we simple people do the same when we change our beliefs? Or when something happens to change our lives?

“You know, I like Chinese philosophy and that lovely tradition they follow in choosing a new name at the end of their lives. After having experienced life, they’re able to pick a name that suits another life. In the end, the names that most suit us are given to us by life. As for those that we come to life bearing, they often oppress us. Let’s just say that I like this idea and decided to be a man with two names.”

His answer, as usual, held no answer, but an astonishing ability to avoid questions.

I didn’t give up, but chased him with my persistence.

“Give me any name you like. I need a name to call you by.”

“My name is Khaled ben Toubal,” he answered in the most normal tone.

I was astonished.

“Khaled ben Toubal? But . . .”

“I know, it’s the name of a hero in one of your novels . . . but it’s also my name.”

I sat on the edge of the couch, watching a man I was only discovering then, and I recalled another man I had met once in another book. He, too, was an artist from Constantine. He was a man I knew by heart, better than myself. Nothing stood between us except masculinity and a body whose left arm had been mutilated by war. Could it possibly be him? I looked at him in disbelief. I expected him to say something, but he didn’t. He just sat there smoking calmly.

For a moment, I thought I was getting closer to the truth, separated from it by the distance of one question. Was Khaled ben Toubal his first name or second? The answer to that question would be scary and decisive, defining the nature of that relationship and the story as well. I knew that he would not answer it so simply, trying to maintain his mystery.

“Is that the name your friends and colleagues use?”

“Of course. It’s also the one I use to sign my articles.”

To my stupor, he then handed me a newspaper sitting next to him and showed me a political article signed by Khaled ben Toubal. I snatched the paper from him, not believing my eyes. After reading Michou’s book I had suspected that he might be a journalist, and I remembered a verse by Michou: “In the absence of sun, learn how to grow on ice.” Next to it, he had written in blue ink: “Or in a newspaper.” But I hadn’t stopped for long at the second verse, under which he had put two lines, as if it were more suited to him:

I have no name.

Mine is a waste of names.

I kept holding the newspaper, while he continued to smoke, ignoring my glances. Perhaps in order to exaggerate his indifference, he turned on the television. There he was intently following a news report, almost forgetting my presence there with him.

The news was showing live coverage of Boudiaf’s tour of the country to explain the concepts of the National Assembly. He was delivering a speech and gesturing with his hands.

“There is a mafia in this country, officials who stole money that didn’t belong to them. I promise you I will declare war on them. The justice department will study all the files and will fulfill its role. I ask all citizens to help them, write to them and give them any information you have. There will no longer be anyone above the law; justice will be above all. It is the people’s right to know the truth and to know where the funds of this country have gone.”

Boudiaf’s speech was improvised, accompanied by cheers and ululations from all those in attendance. The atmosphere in the room changed before that man broke the silence that had fallen between us. He turned toward me.

“They won’t let him accomplish what he’s come to do. I’m certain of it.”

I didn’t know exactly what he meant, for I was still distracted. But I tried to stretch out the conversation.

“Why?”

“Why?” he asked with scorn. “Because they didn’t bring him here to open such explosive files. It’s just a façade behind which they can keep ruling the country and plundering it. His close friends say that he sits alone for hours day and night, searching for the truth he intends to offer to the people in three months’ time, on Independence Day.”

He fell silent for a moment.

“Are you looking for the truth? Everyone is, but everyone is afraid of it. Do you know why?”

“Why?” I murmured.

He slowly put out his cigarette, as if pulverizing it, and then he stood up suddenly and started to unbutton his shirt with only one hand. I remember that I had never seen him use his left hand. That late discovery baffled me, taking me back to that other hero in another story. Before I could think any further, he threw his shirt on the couch and faced me with his bare chest.

“Because truth always expresses itself poorly . . . and sometimes fatally, even when the crime is no more than killing our beliefs.”

I suddenly noticed his left arm. It seemed paralyzed, mutilated at the top, as if someone had performed surgery in two or three places without the slightest regard for appearances. I shivered and was struck by a state of terror . . . not because of what I saw, but because I thought that I was going crazy, unable to separate literature from real life.

It was as if I had dreamt before of the same thing, and here it was actually happening. There I was in front of a man I had created and mutilated myself.

I knew that he was testing me, studying my surprise with acute awareness. I tried to hide my confusion and speak with a sincere voice.

“I’m not concerned with what you think at this moment. But believe me when I say that I love you the way you are. If not, I wouldn’t have created a man who resembled you so closely and lived with him for years in a book.”

“You have always made excellent use of your capacities for love to destroy,” he answered ironically.

“No, I’ve only used my capacities as a writer to imagine.”

“So stop imagining. Life beat you to everything you worked so hard to create. An author’s only achievement is the white space he leaves behind. Every white page is a space stolen from life, because it opens the door on a new story or another book. I’ve come to you from that white space, not from literature as you supposed.”

I didn’t want to argue with him.

“I don’t care to know where you came from. All I know is that I want you.”

“Really,” he said with sarcasm. “I thought you wanted the truth.”

“What confession do you want from me exactly?” I asked, getting more upset.

“I don’t want any confessions from you. I just want you to be honest with yourself and admit that what happens between us as a man and a woman is your main concern and that without it, the story isn’t worth writing.”

“And then?”

“Then nothing. Except that you’re passing near the greater truth and occupying yourself in the search for another, less important, that revolves around the question of who you are. In my opinion, the more important question is why are you here?”

He pressed me into the confession box, but I didn’t know what to say.

“I’m here because, as a writer, I need to look for the truth. As a woman, it’s natural that I look for love. But with you, I can’t make a distinction between the two anymore.”

He replied with the voice of a teacher.

“I’ll show you the way to distinguish them without making a mistake. Truth always expresses itself grossly, and love always looks more beautiful than it is.”

As he talked, he was putting on his shirt again, his right hand trying with difficulty to place the buttons in the buttonhole. Instead of helping button his shirt, my hand reached out to take it off. My lips rolled down the surface of his chest, slipping down to his unmoving arm and covering it with kisses, with the ferocity of passion that alone was capable of making any truth beautiful in its repulsiveness.

As I left him that day, I was filled with conflicting feelings that ranged from pleasure and frustration to astonishment and pain.

To go on a romantic rendezvous and meet someone who has just stepped out of your own book, carrying the same name, the same physical disfigurement, to still want him after all that . . . is bound to leave a flurry of emotions, and questions, inside of you. That name that I had invented and searched so hard to find had left my book and appeared at the bottom of a newspaper article as the name of a man who had no connection to me. But there was another astonishing peculiarity. How could he have the same handicapped arm as the hero of my book?

What astonished me was that this man was continuing a story that had started in a previous novel, as if he were issuing it in a limited, realistic edition. The day he kissed me for the first time in front of his bookshelf, he had said that we were continuing a kiss we had started on page 172 of that book in that same place.

I went through my books, searching through all my novels for page 172. I found that kiss, long, elaborate, and spontaneous, just as it had happened that day between the artist and the writer. Then I remembered the day I borrowed Michou’s book from him. He had said that he was afraid of repeating the same senseless role of the previous book, referring to the heroine in that story who fell in love with the hero’s friend, because of a book. Even I, myself, noticed that I was repeating the behavior of the heroine after that kiss, by borrowing a book.

From the beginning, everything that had happened brought us back to that story, including the city that brought us together. Even the way we talked about bridges and Constantine was a kind of throwback, or a deliberate contradiction, of everything that artist had said in the novel. It was as if time had made him change his mind or modify his opinions due to some disappointment or romantic extremism.

Despite all that, I was still confused. I did not want to believe that the man who had continuously turned my life upside down for a period of six months was Khaled ben Toubal, a character I had created in my novel a few years ago. I had forgotten him in that book, throwing him into the depths of a printing press like one throws a body in the sea after weighing it down with stones, hoping it will never float to the surface. But he had returned.

I knew him by heart. I had lived with him for four hundred pages and almost four years. Then we had separated. His years came to an end when I wrote the last line of the book, and my life without him began.

But which one of us was looking for the other all that time? And who was more in need of the other?

I recalled the answer of a novelist who was once asked why he wrote: “My heroes need me,” he had answered ironically. “They have no one but me on the face of the earth.”

Of course, he was playing with words, admitting that he was an orphan without them. Every novelist is, in the end, an orphan. He is a strange being who abandons everyone to create for himself illusionary family, friends, and loved ones—all creatures of ink—to live among them, sharing their concerns and being subjected to their moods, as though he has no one on the face of the earth but them.

Why was it so strange, then, for this man to become my entire family, replacing my husband, brother, mother, and everyone else around me?

In fact, the only thing I found truly odd was that I had become so attached to this character in particular out of all the heroes I had created. That Pygmalion would fall in love with a statue he had created because of its perfection seemed logical; the puzzling thing was to fall in love with a statue that had miscarried or that a novelist would love a character he had himself disfigured.

That evening, I thought that sitting with my mother would be the best way to escape from myself. I had neglected her to a certain extent after having encouraged her to call some friends in the capital and had made plans for her to suit my own freedom.

She was happy; or at least she looked so to me, as she told me about a distant relative whose son was getting married that coming weekend. We were invited to the wedding ceremony, and from there, it wasn’t difficult for me to figure out my mother’s plans for the next few days.

She had always lived between two weddings, or two vows. Wherever she went, she always stumbled upon somebody preparing for a wedding or someone with a relative who was just returning from the pilgrimage.

Nevertheless, her happiness was never complete; it was missing someone called Nasser. Her dearest wish was to see him get married and have the house fill up with a daughter-in-law to order around and grandchildren to raise and entertain. Now that Nasser had gone, every wedding reminded her of him. She wanted nothing but for him to return to share her last years.

The thing that pained her most was that she hadn’t been prepared for him to leave. Nothing in his character or in the way he lived his life suggested that he could make such a final and surprising decision.

Since Nasser had left three months ago, I had been trying to answer the same question over and over again, only giving her half-truths.

“Why did your brother go away?” she would ask. “Tell me; I know that he tells you everything.”

“He left because he isn’t happy in this country. He wants to try his luck abroad like others. But he’ll be back . . . he promised me that,” I would answer.

“But when? In a few weeks? Months? Years?”

I had no answer.

“When things quiet down a bit and the situation improves somehow.”

“What things?” she asked me. “What situation is going to improve? Didn’t you hear what happened two days ago in Balida? A lady told us today that—”

“I don’t want to know. Please, don’t tell me anything.”

I did not want her to ruin my evening with news of death. She did that every now and then, when she would call me on the phone out of boredom or fear and found nothing to tell me except stories whose like I had never seen even in horror movies.

At that time, the practice of mutilating dead bodies suddenly became widespread. They didn’t even want the souls to rest or enter paradise, so they marked them as infidels or as those who worked for the infidel state. It was a label mostly applied to security men and some poor traffic police, who had become virtually extinct in a few short months, shot or massacred. They were even chased to the cemeteries and assassinated as they were burying their own dead.

The smarter ones would wait for a couple of days before visiting their dead, only to be surprised by someone waiting for them behind the gravestone where they would be buried with their secret. All the graves were open, as if waiting to devour another soul.

What else could my mother add to the series of horrors that I followed in shock day by day, just like any other citizen in my country?

Suddenly she turned back to her old obsession. “Did Nasser give you his address in the letter he sent with his friend?”

“Yes.”

“Write to him then!”

“I’ll do it as soon as I get back to Constantine. He asked about things that I need to check over there.”

Actually, he had not asked me for anything, except for news of my mother and me. I just wanted to postpone writing that letter, because my mind was preoccupied by only one thing—that man. It was exactly like my mother being obsessed with only Nasser, who suddenly started reminding her of my father, who had disappeared over thirty years ago with a bunch of men to plan what would be known as the November Revolution.

Perhaps since then my mother had come to fear all men who departed so abruptly, without leaving an address or a return date. They might not come back, or they might come back when we were no longer waiting for them, having waited so long. One day when we no longer believed that low voice, whispering to us that they would return. Suddenly, a miracle would happen. A hurried hand would ring the doorbell, and the door would open on a tired man, covered with dust. He would draw us to him as if we were little dolls and hold our small bodies very tightly to his chest, kissing us. Being so young, we would never know whether he was laughing or crying.

It was like that amazing story my mother used to tell me. I was five years old and it was during the month of Ramadan. My mother was preparing to break the fast, and I asked her to make one for my father as well because he liked them so much. She kept telling me that he was not there, that he couldn’t possibly come. But I insisted with the stubbornness of a child that he was coming and that she should make him one.

We had just sat at the table when the doorbell rang. My father had come back from the front after a one-year absence. His last visit had been the previous Ramadan. My grandmother burst out in tears, crying, “Hayat told us you were coming but we didn’t believe her!”

I suppose that was why my mother was chasing me with the question of when Nasser would return. She thought that I might still possess that sixth sense or that intuition that only children have that leads them to know things about which adults are ignorant. Of course, I had lost that intuition a long time ago, along with many other beautiful things I had left behind as I grew older.

If I had still possessed it, I would have been able to answer so many questions. One of them—when will that man come back?—was already in the past. Now I wondered who he was and when I would see him again, and where that strange tale was taking me.

As soon as I remembered him, an overwhelming desire to talk to him and hear his voice struck me. I waited for my mother to go to sleep and went to call him.

His phone was busy for a quarter of an hour straight, which both surprised and annoyed me, as if I expected him to have no other person but me in his life to talk to at night.

Finally, the phone rang and his voice came through.

“How are you?”

“I miss you. I thought I’d call you, but your phone was busy.”

“I was talking to a friend in Constantine.”

“Do you still have family there?”

“No, it was my friend Abd al-Haqq.”

“You’re talking to a friend, at this time of night?”

He answered as though denying an accusation.

“He’s the man of the night.”

“What do you mean?”

“He’s a journalist. He works at the newspaper at night.”

“Any news?”

It seemed to me that he was about to say something, but after a short lapse of silence, he answered as if hiding something.

“No, nothing really . . . what about you?”

“I just wanted to hear your voice.”

He was silent before answering.

“And I want you.”

I was surprised by his directness.

“Really? So why did you spend all of yesterday defending the beauty of deprivation?”

“Sometimes we say things we don’t really want to say.”

“What did you really want to say?”

“Nothing, tonight. Don’t expect to hear any logical words from me. I’m drunk with contradictions.”

“Well, I have lots of things to tell you, but I’m afraid of saying anything after you warned me about the phones. Perhaps they’re listening to us right now.”

“Don’t worry. What good is a secret if other people don’t know about it?”

“Are you crazy?” I screamed.

“No, but don’t you like the beauty of a romantic scandal?”

His recklessness surprised me.

“But I’m a married woman.”

“I know. That’s why I marry you and then kill you every passing minute.”

“Why?”

“To make our love legitimate. I want you legally so I can commit with you every sin.”

“Do you really need all that in order to love a woman?”

“Of course, I happen to be a man of principles. At one point you were the most tempting thing I could ever resist.”

“And now?”

“And now nothing. Now I want you with no questions. There isn’t much time left. Come tomorrow. I want to pass all my madness on to you.”

“If I come, do you promise to tell me who you really are?”

“I promise you nothing but pleasure, and you will come, I know.”

“What makes you so sure?”

“Because there’s somebody hovering around me who might steal me away from you. Don’t you feel jealous of someone who could take possession of me forever?”

“Are you getting married?” I asked with disbelief.

He answered with veiled sadness. “You could call it a marriage, with a slight difference in the details. It’s the only everlasting tie that we can neither escape nor choose.”

I did not understand what he meant and concluded that he was joking to make me go.

“I’ll come, but you should watch out for my jealousy. I’m an Aries, and we are known to commit the highest rate of crimes of passion. I’ll bring you the statistics to prove it.”

He was laughing. “Come on. I may be the one who will kill you!”

Why did this man insist on igniting my body and my notebooks? What had changed his convictions? He had always stood at the edge of the illicit, satisfied with a kiss. Could it be true that there was another woman hovering over him? Who could she be? And how could that have happened when I had been speaking to him every day?

I tried to go to sleep, looking for answers to these questions. But then I remembered what he had said: “The time of questions has ended.” So I hid my question marks under my pillow and went to dream about our impending meeting.

My mother’s distraction with that wedding was a gift from the heavens. Knowing how I felt about weddings, and after she had given up on me attending with her, she went alone, leaving me to prepare for the secret joys that I really cared about.

It was noon when I arrived at his house. He opened the door in a watery mood. He seemed as mysterious and unpredictable as the sea.

He kissed me without saying a word.

I sat on the couch facing him, watching him.

“Something in you reminds me of the sea.”

“Did my kiss taste salty?’

“No, more like a deceptive serenity.”

He did not answer.

Silence made us more eloquent. Currents of desire were passing quietly through us, setting us in an earthquake zone at every rendezvous. Desire was the body’s way of silent observation; we loved our sudden silence, and yet we feared it.

We could hear the noon prayer call coming from a distant minaret, and it seemed to me that he was listening to it with special attention. I didn’t dare speak.

As soon as it was over, I stood up. He was preoccupied with smoking a cigarette, and I headed toward the kitchen.

“Can I get myself a glass of water? I’m thirsty.”

He didn’t answer. His hand stretched to block my way, and he pulled me toward him.

“Do you still love Zorba the Greek?” he asked suddenly.

His question surprised me. It sounded like he was accusing me of loving another man.

“Maybe.”

“I think you do. You’re still infatuated with all that is wonderful and deadly. You have passion for those painful losses that overturn all logic.”

“Yes, I do.”

“Come to me, then. I have the sort of pleasure to suit your mood.”

His tone contained a hint of ironic grief that I could not understand. I was about to ask him what he meant, when he pulled me by the hand and took me to another set of questions.

He left me standing for a few moments in the next room, furnished with a wide bed and papers and books covering the modest carpet on the floor. He went to the tape player near the bed and started looking for something in particular among his tapes. He put in a tape by Demis Roussos and came back.

Being in his bedroom embarrassed me.

“You seem to love music.”

He shut the curtains on the only window in the room.

“Music makes us more bearably miserable—haven’t you heard that saying?”

“No.”

“Roland Barthes said it . . . do you know this tape?”

“I know most of Demis Roussos’s songs. I like everything he sings, but I don’t know which tape this is.”

“I don’t know either. I found it here with the other tapes, but there’s one song that you’ll definitely like.”

I didn’t ask which song he meant. I felt suddenly that we were asking the music to save us from the destruction that might follow. Pleasure might lead us to sadness for more than one reason. But a desire frightening in his silence and our inflamed senses removed our emotional resistance, as a Greek voice sang in English of his romantic disappointments in a voice cracking in pain.

We were on the edge of a kiss when the music flooded over us, slowly crawling toward us in time to the lazy rhythm, with a desire so confused it pained me. Like the steps dancing on the pavements of passion under the evening rain, bare feet carried their passionate rhythm to us, wearing the lightness of our lust.

In the presence of Zorba, the sea took off his black sunglasses and a black shirt and sat down to look at me.

Half of him was made of ink, the other half the sea. He stripped me of my questions between the tides and drew me toward my fate. Half of him was shyness, the other half seduction. I was gripped by a fever of kisses.

With one arm, he held me tight. He pinned down my hand and rode me, watching my confusion.

“This is the first time I am able to look from the window of the page to see your body. Let me finally look at you.”

I tried to take cover under a quilt of words, but he reassured me.

“Don’t cover up. I can see you in the darkness of ink, only the lantern of desire shining on your body now. Our love has always lived in the darkness of senses.”

I wanted to ask him why he was so sad, but a hurricane blew away all my questions and scattered me like foam on the bed of desire.

The sea was moving forward, conquering everything in its path, staking banners of masculinity everywhere it passed. With every area he declared occupied or liberated, I discovered how enormous my losses were before him.

He suddenly stood to his feet, as if he had grown restless with the cage of his body and wanted to leave himself to become united with me.

“What are you doing to me?” I asked.

Trees have no choice

But to make love standing.

Come stand with me.

I want to bid my friend farewell in you,

And send him to his final abode.

I was taken aback.

“What are you saying?”

“It is my secret, my poem,” he said as he tried to grasp me.

Suddenly, his words, like his fingers, became matches, burning everything inside of me. I didn’t understand what he meant, or why he wanted to ignite such an overwhelming, frightening fire.

His virility startled me. I wiggled in his arms like a fish, then I started with the ritual of gradual surrender. He suddenly stopped me.

“Do you love me?”

His only arm was infecting me with his passionate ferociousness in an intricate physical imitation. Startled, I answered him.

“Of course I love you. Love has never driven me to sin before you.”

His voice was a mixture of irony and pain.

“How long will I be your first sin?”

“You have plenty of time for more than a beginning.”

“But short are all endings. Now I end up with you. Who gives my life another life, good for more than one beginning?”

His voice had the delayed taste of tears.

I almost asked him if the sea had ever cried before, but it vanished.

The storm had ended. The sea had left me a corpse of love washed up on the shores of astonishment. He took a fleeting look at my body.

One kiss, two kisses.

One wave, two waves.

Then the sea withdrew quietly with the incoming tears.

The sea also left on tiptoes after surging in an uproar, quick and agitated. Could it have also made love out of pain?

The sea withdrew, then, leaving my body between two poems and two tears. But the salt remained. And there I remained, a sea sponge.

At that moment Zorba was continuing his barefoot dance on the shores of tragedy with the awareness of an early disappointment, his arms open wide like a crucified prophet. He pranced around me to the rhythm of continuous stabs, with a ferocious pain that made me masochistic to the point of ecstasy. So I continued to dance with him, shivering like a fish just released from the power of the sea.

When the storm came to an end, the sea lit up a cigarette and smoked as it leaned on questions. When it found the answers, it became a man again.

After lovemaking come the eternal male questions, always. Men phrase them differently according to their intelligence, to assure themselves that their virility is intact.

“I’ve always worried about you in a moment like this. On the bed of reality emotions become less beautiful.”

I reassured him.

“It was lovely what happened between us. I don’t want to know if it was really so or if love made it look more beautiful than it really was.”

I tried to avoid looking at his arm while talking, but in doing so I was gazing at him. In truth, the problem of the novelist is that he cannot help but look closely into things, even those with whom he shared his bed.

He changed his position.

“What is it that you really want to see?” he asked me.

I was surprised by his sarcastic tone of voice, and I answered as if I was trying to justify a sin.

“I want to read the secret history of your body, to know if you’re really Khaled ben Toubal. You act just like he does . . . it’s amazing how much you resemble him. Please put my mind at ease and tell me who you are.”

“All your men are just alike,” he responded sarcastically. Then he added, “But I am not he.”

He pronounced those last words with extreme calmness, with the same tone he used with all his words, as if he weren’t saying something that would change the course of our story.

“Why did you hide the truth from me all this time?”

“There is never only one truth; it isn’t a fixed point. It changes within us and with us. I had no choice but to direct you to what was untrue.

“Do you remember when you said that you loved my body? And I told you that one body may hide another, but you didn’t believe me. You told me that you loved men in their forties. I told you that I’m not the man that you dream of, and you didn’t believe me.

“And to make things even worse, you fell in love with my hands, chasing me with questions about them and asking me how old they were. I told you that you had always loved my complexities, but you didn’t understand. Now, I have nothing but this body with which to answer all your questions.”

“But there was no need for deception. I like it just like it is.”

He smiled.

“You’re dreaming. The only truth is that you were ready for love. It could have come to you disguised as another character in any costume, and say words you longed to hear, or even say nothing at all—you still would have loved me.

“Love adapts to all conditions, and it has a wondrous ability to impart beauty to even average people. The proof of this is that when you discover who I really am, you’ll also find startling details in our story, and that will convince you that you love me, not that other person you were expecting.”

“But you showed me a newspaper with the name of Khaled ben Toubal on it.”

“That’s another truth. It is my name. Or if you like, it’s the name I chose because it resembles me. Since I started receiving death threats, I had to change the name with which I signed my articles. I don’t feel that I stole the name from anyone. I felt that every word I wrote in the newspaper could have been said by that man who came out of a book, if only he had the ability to speak.”

His words astonished me. Was it because we were living in novelistic conditions that everything he did became another novel?

“Aside from all this, who are you?”

He laughed.

“I’m a good reader.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Let’s just say that I read you well and I read you always. I know enough about you to surprise you. I am your other memory that knows what you have forgotten about yourself.”

“But in real life, who are you?”

“In real life, I work as a journalist. You won’t believe me if I tell you that three years ago, my only obsession was to meet you, under the pretext of conducting an interview with you for an article in the paper.

“Actually, I wanted to ask you some questions that concerned no one but me. The publishing of your book coincided with the accident that paralyzed my arm, and so I spent my recovery time reading you. I remember that my friend Abd al-Haqq brought the book to me in the hospital, and he told me as he gave it to me that I would like it. Can you imagine, I was afraid of it even before I read it. Then I was afraid because I had read it so much. It frightened me to stumble upon a hero so much like myself. We shared a common city, common concerns and disappointments, and the same handicap and tastes as well. You were the only thing we didn’t share — you were his lover.

“The day I met you, I felt certain that my life would follow, one way or the other, your story with him. I feared you, and I would consider stopping all communication with you. Oh, if you only knew how much I loved you, and how much I resented you because of a book.”

“Then what?”

“Then nothing. I think that when you chose a hero who had lost an arm, you only wrote to turn things upside down. But life is stranger than the stories we make up; it’s a big trap.

“Imagine, I just wanted some answers from you, nothing more. But life was preparing me for another role. I came to you in a time of questions. The book was finished, and I answered your questions. I have to confess that it was a much nicer role than I had expected, but I never sought it. I was satisfied to go along with my fate and all the coincidences that came with it.”

I finally answered.

“And during all that, you led me through the maze of the script, the secret labyrinth of emotions, the ambushes of romantic trysts.”

“Actually, I was leading you to love. The best kind of love is that which we find while looking for something else. You were looking for a man out of your books, and you created him according to your own measurements. But isn’t it nicer for me to be the man coming into the book and not leaving it?”

“Is that why you’re here today? So that you can claim to have cracked open a beautiful illusion and obtained the woman herself instead of her books, instead of questions that have no answers?”

“Of course not. You know that’s not true. I have words enough to convince you with whatever I like, but I was careful not to break anything in you, or anything between us. I have always thought that desire was the only means of possession, and pleasure is just the beginning of loss.”

“Then what got us into this bed together?”

“Death brought us here.”

“Don’t you see that what you’re saying is an insult to love?”

“On the contrary, it’s just a re-evaluation of love. Don’t ever think that it’s easy to experience pleasure out of pain, or to make love because a friend died. We need a lot of love to avenge death.”

“Who has died to make you feel such grief?”

He sought help in a cigarette before answering.

“Said Muqbel died yesterday, didn’t you hear?”

I answered apologetically.

“I haven’t watched television or read the papers for several days now. Was he a close friend of yours?”

“No, I never even met him. He just became my friend yesterday when his assassins raised him up to the status of friend, with a couple of bullets. Consider, I have 29 friends, most of whom I’ve never met except on the front page of the newspaper on the occasion of their death. He was a close friend of Abd al-Haqq, though. He worked with him at the paper before Abd al-Haqq left for Constantine. I contacted him a short time ago to propose that I write in the same newspaper. We were supposed to meet one of these days.”

“How did they kill him?”

“He was having lunch with his colleague in a small restaurant near the newspaper. A man approached him, and he thought that the man wanted to tell him something. But he pulled out his gun and fired on him, leaving in absolute calmness. Can you believe that the name of the restaurant was Mercy?”

“But why didn’t he take precautions?”

“He did. Ever since they had tried to assassinate him two months ago, he had changed his address, the time he would arrive at the office, the roads he used going home, and the places he frequented. None of this changed his fate. Two weeks before his assassination, he had written a beautiful, heartfelt article describing the daily horror of being a journalist in Algeria. All the newspapers reprinted it today on their front pages. Didn’t you read it?”

“No,” I answered quietly.

He left the room and came back holding a newspaper.

“Read it, and then you’ll mourn a friend.”

As soon as my eyes rested on the headline of the article, he took the newspaper from me and continued to read it himself.

The thief who returns home at night sneaking alongside the walls, he is the one.

The father who asks his children not to reveal the kind of work he does, he is the one.

The bad citizen who drags his tail into the courtroom waiting to be summoned before the judge, he is the one.

The individual who is pushed with the butt of a rifle into a truck after a local raid, he is the one.

He is the one who leaves his home every morning uncertain that he will arrive at his workplace.

He is the one who leaves work in the evening uncertain that he will make it home.

The vagabond who no longer knows where he will spend his night, he is the one.

He is the one who faces all threats in the inner circles of public administrations.

The witness who must swallow everything he knows.

This defenseless citizen.

This man, whose only wish is not to die slaughtered like a sheep, it is he.

The corpse to whom they tie a severed head, he is the one.

He is the one who doesn’t know what to do with his hands, except to write short articles.

He is the one who holds onto hope against all odds—do roses not spring up over piles of filth?

He is all this, but he is only a journalist.

He threw the newspaper on a nearby table and continued to talk.

“How can I bear to mourn a 57-year-old man who faces death with such stubbornness? He published one newspaper article after another in a time when nobody even risks signing his name at the end of an article. He called his column “Juha’s Nail,” declaring that he was here to annoy everyone, making fun of the authorities and terrorists alike.”

He took a drag on his cigarette before continuing in frustration.

“I don’t understand how a nation can assassinate one of its own with such bravado. Usually nations have a maternal instinct—they might get mad at you but they never become your enemy—except for our nation. Here it can kill you without having ever become your enemy. It’s become as Abd al-Haqq said: ‘We do everything in our daily lives as if we’re doing it for the last time. Nobody knows when and under what pretext he will face the anger of the nation.’

“Do you know why I asked you to come here today?” Before I could answer he continued, “Because I was afraid to die before living this moment.”

I scolded him.

“What is this that you’re saying? We’re not here to talk about death.”

“Of course,” he replied sarcastically. “We’re here to play with it and fool it. But it’s there in the schedule of our unconscious thoughts. Pleasure, too, as we lived it a moment ago, with ferocious violence, as if we were about to devour each other physically—it’s only normalizing our relations with death. In a time of abrupt endings, rapid deaths, and ugly little wars that have no name, where a person may face his death without actually being involved in its battles, making love is the only thing we possess to forget ourselves.”

“What about writing?”

“Writing is only our great illusion that others will not forget us.”

“Are you saying this to make me stop writing?”

“I want you to stop fantasizing and succumbing to such illusions. This man who died, this friend of mine is being buried beneath the earth this very minute, just when the evening prayer is sounding he is being delivered to the worms—he also believed in the importance of writing. He believed that his daily column in the newspaper was essential to change our society, and that the reader couldn’t start his day without reading his sarcastic comments and scathing humor. Now, he is no longer able to make anyone laugh or challenge anyone. Death made fun of him and challenged him. He was the one who thought he was changing the world every day with a few lines. But life still goes on after him, and the newspaper is still published without him, and those he died for will soon forget his place on that page where he lived for many years. There is much ungratefulness in journalism.”

His words threw me into a state of sudden depression. I lost my desire to argue, or even to love. Was all of that only for this? Had I taken such a great risk and devised such elaborate plots to be alone with a man who talked to me about death?

“It would have been better if you were only a figure in ink, an illusionary hero in a novel; at least such characters are not assassinated. They don’t die, and we don’t fear for them. So why did you come here if you’re a real man?”

He pulled me toward him.

“I came to pass desire onto you. I came to please you and please myself with you. Those creatures cannot do such things, can they?”

His lips started kissing me again with the same passion, as if we had just met, or as if he had just noticed I was sitting next to him, despite that corpse that lay between us.

I enjoyed following the fluctuations of his love moods. I tried to understand what had excited him as he began invading me again with such extreme physical appetite. I gazed at him as he was fascinated by me. It wasn’t his body that I loved as much as I loved the generosity of his manhood and the moral fiber of his body. His body had such a generous presence that gave and gave just like love, as if he were making up for his shortcomings by giving. Then he would take and take just like impatience.

He had that kind of manhood that was modest in the presence of femininity, as though it owed her everything.

Suddenly he embraced me.

“I have a confession to make, but don’t laugh.”

Before I could answer, he continued.

“I once was jealous of Ziad. Can you believe it? I was never jealous of your husband for even one day, but I was jealous of that creature of ink. He shared the role of the hero with me, and I still feel that he is somewhere in your life and that he got to your body before I did.”

I laughed.

“You’re crazy! That man never existed. I made him up because I like love stories that involve three people. I find that love stories between two people have too much simplicity and naivety for a good novel. So I needed a man to live on the edge of that story, before he became its hero. This is the logic of love in life—we’re always set off by one number.”

“Nevertheless, I still envy him. I wanted a fate identical to his. I’ve even memorized his poems, and I still dream of a great love for a great cause, and a lovely death.”

“The time of lovely deaths has ended. Nobody can die today in an important battle, not even in a novel. All our causes are bankrupt. That’s why I wanted Ziad to die during the Israeli invasion of Beirut. Imagine him, he who was dreaming of returning to Gaza, if he were still alive he’d go directly to prison. Some officer would have put an end to him, imprisoning and torturing other Palestinians for endangering Israeli security. So many illusions died with him—there’s no longer any such thing as Palestine. I’m happy for all those who will come after us, because we’ve saved them years they would have spent trying to fulfill our illusions.”

He sat up, leaving my head on his shoulder while lighting a cigarette. He started to smoke slowly.

“Let’s not talk about Palestine. Answer me this, are you happy with me?”

His question surprised me, and I didn’t know how to answer him.

“When we’re miserable, we know it. But when we’re happy, we’re not aware of it until later. Happiness is always a late discovery.”

“Do I have to wait for the next book to know if you were happy with me or not?” he asked sarcastically.

I laughed.

“Of course not, I can give you an answer now. But in reality, I’ve learned to fear happiness. Every time I’ve found it, I’ve lost it.”

“That’s why you have to live it as a moment in danger. You have to realize that pleasure is plundered, happiness is plundered. Everything beautiful can only be stolen from life, or from others. A person cannot obtain pleasure except by robbery, waiting for death to come and strip him of everything that he has made away with.”

“You reminded me of that film Dead Poets Society. Do you remember the first scene when the students follow their teacher to look at those pictures hung on the walls of their classroom? Those scenes showing the generations of students who had passed through the same school? Remember what the teacher told his students: ‘Make use of the present day. Make your lives outstanding, astonishing, for one day you will cease to be.’”

“I didn’t see that movie,” he commented without interest. “But I bet it was a nice scene.”

“Really? You haven’t seen the movie?”

He was surprised at my tone of voice.

“Should I have seen it?”

I could only justify my surprise at this new discovery with a few muddled words. “I thought that you would have seen it, it won several awards . . . .”

I fell into silence, remembering our story from the beginning. I tried to understand. If we had not met at the film, then who was that man who had sat by my side that day, wearing the same cologne and the same silence?

These questions led me in many directions, when he interrupted me as if apologizing.

“Abd al-Haqq told me about the movie. During my visit to Constantine, he offered to take me to see it. He wanted to write an article about it for the paper, but I had other things to do that day, so he went to see it alone. I’m sure it’s still playing in cinemas in the capital. I’ll try to watch it here so that I can talk to both of you about it, instead of listening to you tell me about every scene.”

He caressed my hair as he continued to speak.

“Would you be happy if I saw it?”

I answered him as I planted a kiss on his cheek.

“Definitely.”

It suddenly seemed to me that I was using Abd al-Haqq’s language, so I added nothing to what I had said.

After a while, I would leave him. He would go back to his mourning, and I would go back to all my questions . . . definitely.

As soon as I was alone that evening, I opened my black notebook, looking through its pages at my story with that man, as I had written it day after day. I started to recall its beginnings, stopping at every juncture trying to understand how that story was born, and where that man came from.

How, over a period of eight months, was he able to avoid all my questions and escape my traps to live inside that book disguised as another man. Then all of a sudden, he surprised me with the truth.

But what truth was that? Was it really the one he confessed to me? Or was it the one that he himself did not know, the one that brought me to him without his knowledge, proving his own words: “There is never only one truth. Truth is not a fixed point. It changes in us and with us. I had no other choice but to show you what was untrue.”

Amidst the questions, my love for him also became a variable truth. In fact, we had a secret time and a shared memory of something very similar to love. We had lived it together even before we had met.

He was the one who said that the best kind of love is that which comes to you while you’re looking for something else. I believed him, and in my awe I forgot what exactly it was I was looking for the day I met him.

There he was in his final role, becoming my reader. How could a reader do all this to the author?

The unconscious aspect of human behavior and decision-making perplexed me; the secret life of emotions amazed me. I remembered one day reading a psychology study that said that our falling in love was not directly related to the ones we loved. It was, rather, because such a person appeared in our lives during a time when we had no emotional immunity, because we had just come out of a bad love experience. We caught love just as we caught a cold between seasons.

I concluded that day that love was a symptom of illness.

Later I read a medical report about the chemistry of love, which said that we committed our most foolish mistakes in the summertime because the sun changed our moods. It had a strange influence on our behavior. Its rays pierced our skin and our blood cells, upsetting our nervous system and turning us into strange people who might do anything.

I thought then that love must be a seasonal condition.

I also read that writing changes our relationships with things, making us fall into sin without feeling any sense of guilt because the mingling of life and literature causes us to imagine at times that we are living out a text we have written in a book. The desire to write seduces you into living things, not because you enjoy doing so, but because you enjoy writing about them.

I concluded that the problem of the writer is that sometimes he does not resist the urge to leave the script. He falls into a literary involvement with life, even in bed.

After much thinking, I decided that what had happened to me had no relation to logic, but was the coincidence of several irrational conditions. That man had entered my life that summer, taking advantage of my lack of emotional immunity and my preoccupation with writing a love story between seasons. His love was nothing but the coincidence of several exceptional conditions.