- from The Untouched Key: Tracing Childhood Trauma in Creativity and Destructiveness by Alice Miller; pp. 59-62: It is easier to search for a way out in mysticism, whereby the person can close his eyes and conceal the truth in eloquent symbolic images. Yet sometimes this approach becomes virtually intolerable too because the power of the quite prosaic truth, the truth of the “little self” so disdained by the mystics, can be inexorable. Particularly for people who at some point in their childhood experienced loving care, this truth won’t allow itself to be silenced completely, even with the help of poetry, philosophy, or mystical experiences. It insists on being heard, like every child whose voice has not been completely destroyed.

The absence or presence of a helping witness in childhood determines whether a mistreated child will become a despot who turns his repressed feelings of helplessness against others or an artist who can tell about his or her suffering. I could cite an abundance of further examples, but I will mention only a few. I must leave it to the reader to verify my statements, to supplement my evidence with new material, or to refute my arguments, as the case may be.

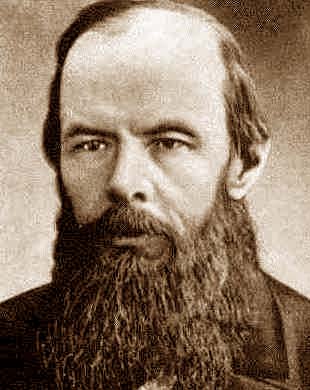

It’s a fact that Dostoyevsky’s father forced his children to read the Bible and tormented them with his greed. I don’t know whether he mistreated them physically, and I must base my assumptions on my knowledge of his son’s novels. But we do know that after his wife’s death, he “led the life of a wastrel, drunkard, and tyrant. He treated his serfs with such cruelty that in 1839 they murdered him most brutally.”

In mid-nineteenth-century Russia, cruelty toward serfs was almost the rule. The elder Dostoyevsky must therefore have treated his serfs especially brutally or perfidiously to drive them to such a dangerous act of revenge. How was this father likely to have treated his own sons? Perhaps a good deal could be gleaned from The Brothers Karamazov. But this novel also shows how difficult it is for sons to acknowledge a father’s wickedness without feeling guilty and without punishing themselves. The serfs were able to free themselves from the domination of their master, but the children were not. Fyodor Dostoyevsky suffered from epilepsy; he searched for God, Whom he could not find. Why didn’t he become a criminal filled with hatred? Because he found a loving person in his mother. Because of her he experienced love, and this was crucial for his later life. Can the explanation be that simple? Yes. But the way his life turned out hung by a thread; it could easily have been completely different.

- from The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoyevsky;pp. xxxii-xxxiii (Introduction by William Mills Todd III): Problems of understanding, truth and falsehood dominate Part Four, and the reader must face them with even less help from the chronicler-narrator than in Parts Two and Three. The sequence of events becomes more difficult to follow, their significance even harder to comprehend. The narrator gives up, devoting his attention to secondary characters and allowing that ‘sometimes it is best for the narrator to confine himself to a simple exposition of events’ (Part Four, chapter I). By chapter 9 he has abdicated the authority to explain the prince’s failure with Aglaya to Radomsky, whose understanding is, by this time, more limited than the reader’s and grounded in a series of inadequate determinist propositions (nerves, epilepsy, the St Petersburg weather, etc.). Aglaya, too, has failed to understand him, grounding her sense of his extraordinary nature in a series of conventionally heroic poses: knight, duelist, judge.

Aglaya’s treatment of the prince in Part Four is one of the most salient of a series of misunderstandings and rejections, rejections which call to mind Nastasya Filippovna’s insightful comment in a letter to Aglaya that Christ should be painted alone, with a child. The plot has not made it easy for these other characters, as the prince is generally presented in terms of negatives or symbols. He is not moralistic or judgemental and does not make conscious choices, acting, instead, compassionately and intuitively. Nor is he formal or ritualistic. He is not conscious of institutions but is vaguely communitarian in his desire to reconcile the characters, uniting them in brotherhood. This makes him particularly vulnerable to the rituals of politeness at the Yepanchin’s party; he can read the faces of children and of characters, such as Rogozhin and Nastasya Filippovna, who are marginal to society, but he cannot read the faces of those who are trained to dissemble. The prince’s values, if we may use so formal a term, centre on beauty, broadly understood to comprise physical and spiritual beauty, natural beauty, the innocence of children and brotherly (not egotistical) love. These are values that the others will not try to grasp and that he cannot express in a logically coherent fashion, only through parable-like narratives. Aglaya specifically forbids him to speak of beauty at her family’s party.

The ending brings together Nastasya Filippovna, Rogozhin and the prince in tragic symmetry. Lying near her, they represent the two aspects of her potential that the prince recognized at first glance, destructively passionate and compassionately gentle. The ending, in turn, leaves the reader with two vexing questions. What has been the prince’s effect on the world of the novel? What has been the world’s effect on the prince? The novel gives many answers to these questions. Ultimately the prince is seen to have ‘fallen’ (the Russian term for epilepsy is the ‘falling sickness’) into a world which expects no Messiah, which cannot understand him and which mistrusts the gifts he brings it, gifts which may themselves become tarnished in this corrosive atmosphere. His passionately ideological speech at the Yepanchins’ party may be just such a tarnished gift.

Whatever Dostoyevsky’s intentions to create a ‘completely beautiful human being’, he did not make the world of The Idiot the world of the Gospels. The corrupt, fearful officials and lawyers of the Gospels seem rather tame beside the characters of this novel. And Christ never had to deal simultaneously with the likes of Aglaya and Nastasya Filippovna. The Christ of the Gospels performed miracles, but always in connection with the faith of those around Him. The world of this novel is very different: a world of cynicism, greed and rampant egocentricity. Its sense of beauty is superficial, not spiritual, and, in the final analysis, it extends the prince no understanding. And he can bring it no miracles.

- pp. xi-xiii [Introduction]: The most reckless diagnosis no doubt belongs to Emile Hennequin:

Dostoyevksy’s ultimate originality, the feature which distinguished and characterized him, is his enormous imbalance between feeling and reason. This man sees things and beings with the vividness and surprise of someone half insane. And since anticipation neither prepares him for their movement nor the need for reasoning impels him to sort out causes and effects, he looks wildly upon a spectacle which assaults his senses in disconnected shocks. Likewise, an intellect little developed, to which the senses ceaselessly bear disconnected impressions, would be at a loss to imagine the idea of development, be it in a narrative or in a characterization, and would conceive instead uncertainty in a story and instability in a soul...Hence, once these aptitudes are amplified to the level of genius, the marvellous design of Dostoyevsky’s characters; hence, above all, their carnal, wild, violent, brutal, unintelligent nature, which Dostoyevsky must have discovered latent in his own unpolished character, more animal than spiritual.

As a description of Dostoyevsky’s characters in their most desperate moments, this has some plausibility; and the narrator of The Idiot--by no means equal in intelligence and understanding to its author--seems often at a loss when dealing with the development of plot and character. And to be sure Dostoyevsky himself could be irascible, unreasonable and, in polite society, notoriously ‘unpolished’. Recent novels by John Coetzee (The Master of St Petersburg) and Leonid Tsypkin (Summer in Baden-Baden) have imagined these aspects of the author’s personality more successfully than the scholars and psychologists. Dostoyevsky’s was, indeed, a life lived on the edge of physical breakdown, financial ruin and mental depression. By his own estimate he endured, beginning at the age of twenty-six, an epileptic seizure every three weeks.

All of these sensational details of his life and work are, however, subject to qualification. James Rice, in a thorough and insightful study of Dostoyevsky’s illness, notes that unlike the hero of The Idiot, Dostoyevsky could generally anticipate his seizures and rarely suffered them in public. He was able, ultimately, to control and terminate his obsession with gambling, and to write his way out of debt. The madness, violence and irrationality of his characters--denigrated by his contemporary Russian critics and celebrated by his first foreign ones--were more often than not creative transformations of his childhood reading of early nineteenth-century European literature. In ways unrecognized by his first European readers, he was returning them the themes, plots and characters of their own Romantic fiction, drama and poetry.

- from The Body Never Lies: The Lingering Effects of Cruel Parenting by Alice Miller [Translated by Andrew Jenkins]; pp. 43-45: The works of the Russian writers Dostoevsky and Chekhov meant a great deal to me in my youth. My later studies of these authors have shown me how faultlessly the disassociative mechanism functions, not only today but also over a century ago. When I finally succeeded in giving up the illusions I had entertained about my parents and recognized the effects of their deeds on my life as a whole, this also opened my eyes to facts I had formerly not attributed any importance to. Janko Lavrin’s biography of Dostoevsky informed me that in later life his father, initially an army doctor, inherited an estate with more than a hundred serfs. His treatment of these people was so brutal that they eventually summoned up the courage to murder him. The conclusion I drew from this was that his brutality must have far exceeded the norm, for what other explanation could there be for the fact that these cowed vassals elected to run the risk of banishment for their crime, rather than suffering any longer under this reign of terror? It thus seemed more than plausible that his eldest son would also have been subjected to some kind of cruelty. Accordingly, I resolved to investigate how the author of so many world-famous novels had managed to come to terms with his own personal history. I was of course familiar with his portrayal of a merciless father in The Brothers Karamazov, but I wanted to find out what his relationship with his real father was like. First I looked for relevant passages in his letters. I read them all but found not one single instance of a letter to his father. The one and only mention of him was obviously designed to testify to the son’s consummate respect and unconditional love for him. On the other hand, almost all his letters to other people contained complaints about his financial situation and requests for financial support. To my mind, all these letters clearly express a child’s fear of the constant threat to his very existence, coupled with the desperate hope that the addressee will understand his distress and be kindly disposed to him.

It is a well-known fact that Dostoevsky’s health was extremely poor. He suffered from chronic insomnia and complained of dreadful nightmares, in which we may assume that his childhood traumas found a way of expressing themselves without his becoming consciously aware of the fact. We also know that for decades Dostoevsky suffered epileptic fits. But his biographers make little or no indication of any connection between these attacks and his traumatic childhood. They have been equally blind to the yearning for a merciful destiny that is clearly recognizable in his addiction to roulette. Though his wife helped him to overcome this addiction, she was unable to function as an enlightened witness because at the time it was thought to be even more reprehensible to level accusations at one’s own father than it is now.

- from The Best Short Stories of Dostoevsky; [(NOTES FROM THE UNDERGROUND) pp. 135-136 [Chapter VII]: Oh, tell me who was it first said, who was it first proclaimed that the only reason man behaves dishonourably is because he does not know his own interests, and that if he were enlightened, if his eyes were opened to his real normal interests, he would at once cease behaving dishonourably and would at once become good and honourable because, being enlightened and knowing what is good for him, he would see that his advantage lay in doing good, and of course it is well known that no man ever knowingly acts against his own interests and therefore he would, as it were, willy-nilly start doing good. Oh, the babe! Oh, the pure innocent child! When, to begin with, in the course of all these thousands of years has man ever acted in accordance with his own interests? What is one to do with the millions of facts that bear witness that man knowingly, that is, fully understanding his own interests, has left them in the background and rushed along a different path to take a risk, to try his luck, without being in any way compelled to do it by anyone or anything, but just as though he deliberately refused to follow the appointed path, and obstinately, wilfully, opened up a new, a difficult, and an utterly preposterous path, groping for it almost in the dark. Well, what does it mean but that to man this obstinacy and wilfulness is pleasanter than any advantage....Advantage! What is advantage? Can you possibly give an exact definition of the nature of human advantage? And what if sometimes a man’s ultimate advantage not only may, but even must, in certain cases consist in his desiring something that is immediately harmful and not advantageous to himself? If that is so, if such a case can arise, then the whole rule becomes utterly worthless. What do you think? Are there cases where it is so? You are laughing? Well, laugh away, gentlemen, only tell me this: have men’s advantages ever been calculated with absolute precision? Are there not some which have not only fitted in, but cannot possibly be fitted in any classification? You, gentlemen, have, so far as I know, drawn up your entire list of positive human values by taking the averages of statistical figures and relying on scientific and economic formulae. What are your values? They are peace, freedom, prosperity, wealth, and so on and so forth. So that any man who should, for instance, openly and knowingly act contrary to the whole of that list would, in your opinion, and in mine, too, for that matter, be an obscurantist or a plain madman, wouldn’t he? But the remarkable thing surely is this: why does it always happen that when all these statisticians, sages, and lovers of the human race reckon up human values they always overlook one value? They don’t even take it into account in the form in which it should be taken into account, and the whole calculation depends on that. What harm would there be if they did take it, that value, I mean, and add it to their list? But the trouble, you see, is that this peculiar good does not fall under any classification and cannot be included in any list.

- pp. 137-138: What is important is that this good is so remarkable just because it sets at naught all our classifications and shatters all the systems set up by the lovers of the human race for the happiness of the human race. In fact, it plays havoc with everything. But before I tell you what this good is, I should like to compromise myself personally and I therefore bluntly declare that all these theories which try to explain to man all his normal interests so that, in attempting to obtain them by every possible means, he should at once become good and honourable, are in my opinion nothing but mere exercises in logic. Yes, exercises in logic. For to assert that you believed this theory of the regeneration of the whole human race by means of the system of its own advantages is, in my opinion, almost the same as--well, asserting, for instance, with Buckle, that civilisation softens man, who consequently becomes less bloodthirsty and less liable to engage in wars. I believe he argues it very logically indeed. But man is so obsessed by systems and abstract deductions that he is ready to distort the truth deliberately, he is ready to deny the evidence of his senses, so long as he justifies his logic.

- pp. 142-143 [Chapter VIII]: For when one day desire comes completely to terms with reason we shall of course reason and not desire, for it is obviously quite impossible to desire nonsense while retaining our reason and in that way knowingly go against our reason and wish to harm ourselves. And when all desires and reasons can be actually calculated (for one day the laws of our so-called free will are bound to be discovered) something in the nature of a mathematical table may in good earnest be compiled so that all our desires will in effect arise in accordance with this table. For if it is one day calculated and proved to me, for instance, that if I thumb my nose at a certain person it is because I cannot help thumbing my nose at him, and that I have to thumb my nose at him with that particular thumb, what freedom will there be left to me, especially if I happen to be a scholar and have taken my degree at a university? In that case, of course, I should be able to calculate my life for thirty years ahead. In short, if this were really to take place, there would be nothing left for us to do: we should have to understand everything whether we wanted to or not. And, generally speaking, we must go on repeating to ourselves incessantly that at a certain moment and in certain circumstances nature on no account asks us for our permission to do anything; that we have got to take her as she is, and not as we imagine her to be; and that if we are really tending towards mathematical tables and rules of thumb and--well--even towards test tubes, then what else is there left for us to do but to accept everything, test tube and all. Or else the test tube will come by itself and will be accepted whether you like it or not....

The Dostoevsky Archive: Firsthand Accounts of the Novelist from Contemporaries’ Memoirs and Rare Periodicals by Peter Sekirin; pp. 135-136: Students from the Moscow University went to St. Petersburg to see Dostoevsky, and to ask for his advice. Here is what Dostoevsky told them:

In the most terrible periods of my life, when everybody left me, there was only one Being which supported me all the time. This Being was God. He never rejected me in His support. I feel from my own experience that there is nothing worse than atheism or the lack of faith. To all people who want to make sure that this is true, I suggest to them to go to prison. If they do not commit suicide there, then they become real believers.

You can create any ideas, you can destroy any theories created by humans, but do not touch the notion of God. He came to Earth before you, and He cannot be destroyed by you. Those who live without Him feel emptiness and darkness in their hearts, and they have nothing inside. You feel desperate and lonely, if you do not have faith....Look around yourself--you are alone. And Jesus Christ was supported by all the heavenly forces. And what is behind you?...If you do not believe, try to behave as I suggest, start to believe without any doubts and hesitations, without any pre-conditions, and then you will understand that it will help to support any enterprise, any business you do, and any failure of yours will not seem terrible to you, and then everything will become possible for you in this life....At present I want to express my views on faith in a novel.

Selected Letters of Fyodor Dostoyevsky [Edited by Joseph Frank and David I. Goldstein/Translated by Andrew R. MacAndrew]; p. 23: Those Muscovites are unspeakably vain, stupid, and quarrelsome. In his last letter, Karepin for some unearthly reason advised me not to get too enthusiastic about Shakespeare! He says that Shakespeare is just like a soap bubble. I wanted you to know about this idiotic resentment of Shakespeare. How in the world does Shakespeare come into the picture? You should have seen the letter I wrote him! In one word, it was a model piece of polemics. I really gave it to him. My letters are a chef d’oeuvre of lettristics.

The Brothers Karamazov: A Novel in Four Parts with Epilogue (Translated and Annotated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky); pp. 18-19: He was then only twenty years old (his brother Ivan was in his twenty-fourth year, and their elder brother, Dmitri, was going on twenty-eight). First of all I announce that this young man, Alyosha, was not at all a fanatic, and, in my view at least, even not at all a mystic. I will give my full opinion beforehand: he was simply an early lover of mankind, and if he threw himself into the monastery path, it was only because it alone struck him at the time and presented him, so to speak, with an ideal way out for his soul struggling from the darkness of worldly wickedness towards the light of love. And this path struck him only because on it at that time he met a remarkable being, in his opinion, our famous monastery elder Zosima, to whom he became attached with all the ardent first love of his unquenchable heart. However, I do not deny that he was, at that time, already very strange, having been so even from the cradle. Incidentally, I have already mentioned that although he lost his mother in his fourth year, he remembered her afterwards all his life, her face, her caresses, “as if she were standing alive before me.” Such memories can be remembered (everyone knows this) even from an earlier age, even from the age of two, but they only emerge throughout one’s life as specks of light, as it were, against the darkness, as a corner torn from a huge picture, which has all faded and disappeared except for that little corner. That is exactly how it was with him: he remembered a quiet summer evening, an open window, the slanting rays of the setting sun (these slanting rays he remembered most of all), an icon in the corner of the room, a lighted oil-lamp in front of it, and before the icon, on her knees, his mother, sobbing as if in hysterics, with shrieks and cries, seizing him in her arms, hugging him so tightly that it hurt, and pleading for him to the Mother of God, holding him out from her embrace with both arms towards the icon, as if under the protection of the Mother of God...and suddenly a nurse rushes in and snatches him from her in fear. What a picture! Alyosha remembered his mother’s face, too, at that moment: he used to say that it was frenzied, but beautiful, as far as he could remember. But he rarely cared to confide this memory to anyone. In his childhood and youth he was not very effusive, not even very talkative, not from mistrust, not from shyness or sullen unsociability, but even quite the contrary, from something different, from some inner preoccupation, as it were, strictly personal, of no concern to others, but so important for him that because of it he would, as it were, forget others. But he did love people; he lived all his life, it seemed, with complete faith in people, and yet no one ever considered him either naive or a simpleton. There was something in him that told one, that convinced one (and it was so all his life afterwards) that he did not want to be a judge of men, that he would not take judgment upon himself and would not condemn anyone for anything. It seemed, even, that he accepted everything without the least condemnation, though often with deep sadness. Moreover, in this sense he even went so far that no one could either surprise or frighten him, and this even in his very early youth.

- The Brothers Karamazov; book jacket: Dostoevsky’s last, towering novel summed up his life and work. THE BROTHERS KARAMAZOV has long been recognized as a zenith of Western art; seminal modern thinkers such as Freud and Einstein have acknowledged it as an encapsulation of philosophy, psychology, and humanity’s struggle for faith and salvation.

pp. 7-8: Precisely how it happened that a girl with a dowry, a beautiful girl, too, and moreover one of those pert, intelligent girls not uncommon in this generation but sometimes also to be found in the last, could have married such a worthless “runt,” as everyone used to call him, I cannot begin to explain. But then, I once knew a young lady still of the last “romantic” generation who, after several years of enigmatic love for a certain gentleman, whom, by the way, she could have married quite easily at any moment, ended up, after inventing all sorts of insurmountable obstacles, by throwing herself on a stormy night into a rather deep and swift river from a high bank somewhat resembling a cliff, and perished there decidedly by her own caprice, only because she wanted to be like Shakespeare’s Ophelia. Even then, if the cliff, chosen and cherished from long ago, had not been so picturesque, if it had been merely a flat, prosaic bank, the suicide might not have taken place at all.

p. 9: In the intermissions, he drove over most of the province, tearfully complaining to all and sundry that Adelaida had abandoned him, going into details that any husband ought to have been too ashamed to reveal about his married life. The thing was that he seemed to enjoy and even feel flattered by playing the ludicrous role of the offended husband, embroidering on and embellishing the details of the offense. “One would think you had been promoted, Fyodor Pavlovich,” the scoffers used to say, “you’re so pleased despite all your woes!” Many even added that he was glad to brush up his old role of buffoon, and that, to make things funnier still, he pretended not to notice his ridiculous position. But who knows, perhaps he was simply naive.

p. 3 (From the Author): But suppose they read the novel and do not see, do not agree with the note-worthiness of my Alexei Fyodorovich? I say this because, to my sorrow, I foresee it. To me he is noteworthy, but I decidedly doubt that I shall succeed in proving it to the reader. The thing is that he does, perhaps, make a figure, but a figure of an indefinite, indeterminate sort. Though it would be strange to demand clarity from people in a time like ours. One thing, perhaps, is rather doubtless: he is a strange man, even an odd one. But strangeness and oddity will sooner harm than justify any claim to attention, especially when everyone is striving to unite particulars and find at least some general sense in the general senselessness. Whereas an odd man is most often a particular and isolated case. Is that not so?

Now if you do not agree with this last point and reply: “Not so” or “Not always,” then perhaps I shall take heart concerning the significance of my hero, Alexie Fyodorovich. For not only is an odd man “not always” a particular and isolated case, but, on the contrary, it sometimes happens that it is precisely he, perhaps, who bears within himself the heart of the whole, while the other people of his epoch have all for some reason been torn away from it for a time by some kind of flooding wind.

I would not, in fact, venture into these rather vague and uninteresting explanations but would simply begin without any introduction...

pp. 19-20: Thus he possessed in himself, in his very nature, so to speak, artlessly and directly, the gift of awakening a special love for himself. It was the same with him at school, too, and yet it would seem that he was exactly the kind of child who awakens mistrust, sometimes mockery, and perhaps also hatred, in his schoolmates. He used, for instance, to lapse into revery and, as it were, set himself apart. Even as a child, he liked to go into a corner and read books, and yet his schoolmates, too, loved him so much that he could decidedly be called everyone’s favorite all the while he was at school. He was seldom playful, seldom even merry, but anyone could see at once, at a glance, that this was not from any kind of sullenness, that, on the contrary, he was serene and even-tempered. He never wanted to show off in front of his peers. Maybe for that very reason he was never afraid of anyone, and yet the boys realized at once that he was not at all proud of his fearlessness, but looked as if he did not realize that he was brave and fearless. He never remembered an offense. Sometimes an hour after the offense he would speak to the offender or answer some question with as trustful and serene an expression as though nothing had happened between them at all. And he did not look as if he had accidentally forgotten or intentionally forgiven the offense; he simply did not consider it an offense, and this decidedly captivated the boys and conquered them. There was only one trait in him that in all the grades of his school from the lowest even to the highest awakened in his schoolmates a constant desire to tease him, not out of malicious mockery but simply because they found it funny. This trait was a wild, frantic modesty and chastity. He could not bear to hear certain words and certain conversations about women. These “certain” words and conversations, unfortunately, are ineradicable in schools. Boys, while still almost children, pure in mind and heart, very often like to talk in classes among themselves and even aloud about such things, pictures and images, as even soldiers would not speak of; moreover, many things that soldiers themselves do not know or understand are already familiar to still quite young children of our educated and higher society. There is, perhaps, no moral depravity yet, and no cynicism either of a real, depraved, inner sort, but there is external cynicism, and this is not infrequently regarded among them as something refined, subtle, daring, and worthy of emulation. Seeing that “Alyoshka Karamazov” quickly put his fingers in his ears when they talked “about that,” they would sometimes purposely crowd around him, pull his hands away by force, and shout foul things into both his ears, while he struggled, slipped to the floor, lay down, covered his head, all without saying a word to them, without any abuse, silently enduring the offense. In the end, however, they left him alone and no longer teased him with being “a little girl”; moreover, they looked upon him, in this respect, with compassion. Incidentally, he was always among the best of his class in his studies, but was never the first.

The Idiot by Fyodor Dostoyevsky (Translated with Notes by David McDuff); pp. 631-638 [PART FOUR, CHAPTER 7]: ‘Wasn’t it this Pavlishchev that there was some episode about...a strange one...with an abbe...an abbe...I’ve forgotten which abbe it was, but everyone was talking about it at the time,’ the ‘dignitary’ said, as if recollecting.

‘It was Abbe Goureau, the Jesuit,’ Ivan Petrovich reminded him, ‘yes, sir, there are most excellent and most worthy men, sir! Because say what you like, he was a man of good family, with a fortune, a chamberlain and if he had...continued to serve...And then he suddenly gave up the service, and everything, in order to go over to Catholicism, and became a Jesuit, and more or less openly, too, with a kind of delight. Truly, he died at the right time...yes; everyone said it at the time...’

The prince was beside himself.

‘Pavlishchev...Pavlishchev went over to Catholicism? That cannot be!’ he exclaimed in horror.

‘Well, “that cannot be”,’ Ivan Petrovich mumbled sedately, ‘is putting it a little strongly, you must admit, my dear Prince...However, you have such a high opinion of the deceased...indeed, he was the kindest of men, to which I ascribe, in the main, that wily old fox Goureau’s success. But really, speaking personally, don’t ask me how much fuss and bother I later experienced on account of that matter...and precisely with that selfsame Goureau! Imagine,’ he suddenly addressed the elderly gentleman, ‘they even wanted to advance claims in connection with the will, and at the time I even had to resort to the most, er, energetic measures...because they were masters of the craft! Extraordinary! But, thank God, it happened in Moscow, I at once went to see the count, and we...put some sense into them...’

‘You can’t imagine how you have upset and shocked me!’ the prince exclaimed again.

‘I am sorry; but it really is all nonsense and would have ended in nonsense, as usual; I’m convinced of it. Last summer,’ he turned again to the elderly gentleman, ‘Countess K. also entered some Catholic convent abroad; our people don’t seem to be able to hold out, once they submit to those...sly-boots...especially abroad...’

‘I think it’s all caused, I think, by our...weariness,’ the elderly gentleman mumbled authoritatively. ‘Well, and their manner of preaching...it’s elegant, unique...and they know how to frighten people. They also frightened me in Vienna, in thirty-two, I assure you; only I didn’t submit, and ran away from them, ha-ha!’

‘I heard, my dear, that you ran away from Vienna to Paris with the society beauty Countess Levitskaya, leaving your post, and it wasn’t the Jesuit you ran away from,’ Belokonskaya suddenly retorted.

‘Well, but I mean, it was from the Jesuit, that’s how it turned out, it was the Jesuit I was running away from!’ the elderly gentleman interjected, bursting into laughter at the pleasant recollection. ‘You seem very religious, and that is so rarely encountered in a young man nowadays,’ he turned affectionately to Prince Lev Nikolayevich, who was listening with his mouth open and was still shocked; the elderly gentleman apparently wanted to find out more about the prince; for several reasons he had been begun to interest him greatly.

‘Pavlishchev was a brilliant intellect and, a Christian, a true Christian,’ the prince declared suddenly. ‘How could he have submitted to a faith that is...unchristian? Catholicism is the same thing as an unchristian faith!’ he added suddenly, his eyes beginning to flash, and he stared ahead of him, somehow taking them all in with his eyes.

‘Well, that is too much,’ muttered the elderly gentleman, giving Ivan Fyodorovich a look of surprise.

‘How is that, Catholicism an unchristian faith?’ Ivan Petrovich turned round on his chair. ‘What sort of faith is it, then?’

‘It’s an unchristian faith, that is number one!’ the prince began to speak again, in extreme excitement and with excessive sharpness. ‘That is number one, and number two is that Roman Catholicism is even worse than atheism itself, that is my opinion! Yes! That’s my opinion! Atheism merely preaches zero, but Catholicism goes further: it preaches a distorted Christ, slandered and desecrated by it, the opposite of Christ! It preaches the Antichrist, I swear to you, I assure you! That is my personal and long-established conviction, and it has been a source of torment to me...Roman Catholicism believes that without universal state power the Church will not endure upon earth, and cries: ‘Non possumus!’ In my view, Roman Catholicism is not even a faith, but is decidedly a continuation of the Western Roman Empire, and in it everything, beginning with faith, is subordinated to that idea. The Pope seized the earth, an earthly throne, and took up the sword; ever since then it has all gone like that, except that to the sword they’ve added lies, slyness, deception, fanaticism, superstition and evil-doing, and played with the people’s most sacred, truthful, simple, fiery emotions, exchanging everything, everything for money, for base, earthly power. And isn’t that the teaching of the Antichrist? How could atheism have failed to originate from them? Atheism originated from them, from Roman Catholicism itself! First of all, atheism took its origin in them: could they believe in themselves? It gained strength from the revulsion that was felt for them; it is the result of their lies and spiritual impotence! Atheism! So far, in our land it’s only the upper classes who do not believe, as Yevgeny Pavlovich put it so splendidly the other day, having lost their roots; but there, in Europe, now, enormous masses of the ordinary people are starting not to believe – it used to be because of darkness and lies, but now it’s because of fanaticism, hatred of the Church and Christianity!’

The prince stopped to draw breath. He had been talking terribly fast. He was pale and gasping. They all exchanged glances; but at last the elderly gentleman openly burst into laughter. Prince N. took out his lorgnette and examined the prince steadily. The little German poet crept out of the corner and moved closer to the table, smiling an ominous smile.

‘You very much exaggerate,’ Ivan Petrovich drawled with a certain degree of boredom, and even as if he had something on his conscience. ‘In the Church over there, there are also representatives who are worthy of all respect and are virtuous...’

‘I wasn’t talking about individual representatives of the Church. I was talking about the essence of Roman Catholicism, it is Rome of which I speak. Can a Church completely disappear? I never said that!’

‘Agreed, but that is all well known and even--superfluous, and...belongs to theology...’

‘Oh no, oh no! Not just to theology, I assure you, it doesn’t! It concerns us far more closely than you suppose. That is the whole of our error, that we cannot yet see that this matter is not just a purely theological one! I mean, socialism is also a result of Catholicism and the essence of Catholicism! It also, like its brother atheism, originated in despair, opposed to Catholicism in a moral sense, in order to replace the last moral power of religion, in order to assuage the thirst of a spiritually thirsting humanity and to save it not by Christ, but by coercion! It is also freedom by coercion, it’s unification by the sword and by blood! “Do not dare to believe in God, do not dare to have property, do not dare to have individuality, fraternite ou la mort, two million heads!”* By their works ye shall know them--it is written! And do not suppose that all this has been so innocent and innocuous for us; oh, we need to rebuff it, and soon, soon! Our Christ must shine out as a rebuff to the West, the Christ we have preserved and whom they have not known! Not slavishly swallowing the Jesuits’ hook, but carrying our Russian civilization to them, we must now stand before them, and let no one among us say that their preaching is elegant, as someone said just now...’

‘But permit me, permit me,’ Ivan Petrovich began to grow dreadfully perturbed, looking round him, and even starting to lose his nerve. ‘All your ideas are, of course, praiseworthy and full of patriotism, but it is all in the highest degree exaggerated, and...we had even better drop the subject...’

‘No, it isn’t exaggerated, it’s rather understated; understated indeed, because I’m not able to express myself properly, but...’

‘But permit me!’

The prince fell silent. He sat straight up in his chair and, motionless, looked at Ivan Petrovich with a fiery stare.

‘I think the incident with your benefactor has shaken you too much,’ the elderly gentleman observed, kindly and not losing his calm. ‘You are ignited...perhaps because of your seclusion. If you lived with people more, and you would, I hope, be gladly accepted in society as a remarkable young man, then you would, of course, calm your animation and see that all this is far more simple...and moreover such rare instances...occur, in my view, partly because of our satiety and partly because of...boredom.’

‘Precisely, precisely so!’ exclaimed the prince. ‘A most magnificent idea! Precisely “because of boredom, because of our boredom”, not because of satiety, on the contrary, because of thirst...not satiety, you are wrong there! Not only thirst, but even inflammation, a feverish thirst! And...and do not suppose that this is on such a small scale that it may merely be laughed at; excuse me, but one must be able to have prescience! No sooner do our people reach a shore, no sooner do they come to believe that it is a shore, than they rejoice in it so much that they at once go to the last extreme; why is that? I mean, here you are being astonished at Pavlishchev, you ascribe it all to his insanity or kindness, but that is wrong! And it is not us alone, but the whole of Europe that is astonished by our passionate Russian temperament: in our country, if a man goes over to Catholicism, he unfailingly becomes a Jesuit, and one of the most clandestine sort, at that; if he becomes an atheist, he will at once begin to demand the eradication of belief in God by coercion, that is, by the sword! Why is that, why such instant frenzy? Do you really not know? It’s because he has found the fatherland he failed to espy here, and is filled with joy; he has found a shore, a soil, and has rushed to kiss it! You see, it is not from vanity alone, not from mere sordid vain emotions that Russian atheists and Russian Jesuits proceed, but from a spiritual pain, a spiritual thirst, a yearning for something more exalted, for a firm shore, a motherland in which they have ceased to believe, because they have never known it! It is so easy for a Russian to become an atheist, easier than for anyone else in the whole world! And our people do not simply become atheists, they unfailingly believe in atheism, as in a new creed, never noticing that they have come to believe in a zero. That is what our thirst is like! “He who has no soil beneath him has no God either.” That expression is not my own. It’s the expression of a merchant, an Old Believer, whom I met when I was travelling. He, it’s true, didn’t express it like that, he said: “He who has renounced his native land has renounced his God as well.” I mean, just think, highly educated people in our country have even taken up flagellantism . . . Though, as a matter of fact, in that case is flagellantism any worse than nihilism, Jesuitism or atheism? It is even, perhaps, a bit deeper than them! But that is the length to which their yearning has gone!...Reveal the shore of the New World to Columbus’s thirsting and inflamed fellow-travellers, reveal the Russian World to a Russian, let him find that gold, that treasure hidden from him in the earth! Show him in the future the renewal of all mankind and its resurrection, perhaps by Russian thought alone, by the Russian God and Christ, and you will see what a mighty and truthful, wise and meek giant will grow before an amazed world, amazed and frightened, because they expect from us only the sword, the sword and coercion, because they cannot imagine us, judging by their own standards, without barbarism. And that is how it has been hitherto, and that is how it will increasingly continue! And...’

But here a certain event took place, and the orator’s speech was cut short in the most unexpected manner.

All this feverish tirade, all this flow of impassioned and agitated words and rhapsodic ideas, jostling, as it were, in a kind of turmoil and skipping from one to the other, all this foretold something dangerous, something peculiar in the mood of the young man who had so suddenly boiled over, apparently for no reason. Of those who were present in the drawing room, all who knew the prince marvelled fearfully (and some with embarrassment) at his outburst, which was so little in harmony with his customary and even timid reserve, his rare and peculiar tact on certain occasions, and his instinctive sense of the higher proprieties. They could not understand what had caused it: it was surely not the news of Pavlishchev’s death. In the ladies’ corner he was being viewed as a madman, and Belokonskaya confessed later that ‘one more minute and she would have wanted to run away’. The ‘elderly gentlemen’ were almost dumbfounded at first; the general-superior looked with stern displeasure from his chair. The engineer-colonel sat completely immobile. The little German even turned pale, but went on smiling his false smile, casting glances at the others: how would the others respond? However, all this and the ‘whole scandal’ might have been resolved in the most ordinary and natural way, perhaps, even within a minute; Ivan Fyodorovich, who was extremely surprised, but had recovered himself earlier than the rest, also began to try to stop the prince several times; not having achieved success, he was now making his way towards him, with firm and decisive ends in view.

* An allusion to a passage in Chapter 37 of Alexander Herzen's My Past and Thoughts, where Herzen reflects on the view of the nineteenth-century German republican publicist Karl Heinzen that in order to create world revolution it would be sufficient 'to kill two million people'.

p. xiii: By countering the initial response to Dostoyevsky as an untutored savage, such detailed studies of his texts and writing process enable us to understand him as a gambler in a new and different sense. While he is famous for his compulsive gambling sprees at a game of chance, roulette, his greatest gamble was one that he indulged not for six years, but for nearly four decades: that he could support himself exclusively by his writing, by becoming one of Russia’s first truly professional writers.

pp. xvi-xvii: Nabokov, mocking Dostoyevsky’s Russian nationalism, could not resist the temptation to call him ‘the most European of the Russian writers’, and Dostoyevsky’s early letters and late journalistic essays, to say nothing of his fiction, show an intense, enduring fascination with several interrelated genres imported into Russia by translators and the literary journals. The German writer Friedrich Schiller gave him a sense of life as festival, an ecstatic sense that humanity could be perfected and that people could become brothers through achieving a harmonious balance between mental, emotional and sensual activities. Such visions extend from Dostoyevsky’s early teens through Prince Myshkin’s visions in The Idiot to Dmitri Karamazov’s confessions in verse and Alyosha Karamazov’s final speech. Gothic fiction, another youthful fascination, transects all of Dostoyevsky’s fiction with mysterious settings, characters beset by mental dysfunction and plots set in motion by violations of the divine order. If we could use the term ‘Gothic’ in its historical sense and not in its present pejorative one, we would find much of it in Dostoyevsky, whose mature fiction centres around daring challenges to moral and divine authority. French social Romanticism (Georges Sand, Victor Hugo, Honore de Balzac, the Utopian Socialists) figures no less prominently in his early reading, and it gave him lessons in criticizing contemporary society and dreaming of a potentially harmonious social order. Dostoyevsky would begin his literary career with a translation of Balzac’s Eugenie Grandet (1833). Canonical works sanctified by Romanticism, such as Shakespeare’s, would lend Dostoyevsky citations and plot structures for the rest of his career.

The Best Short Stories of Dostoevsky (Translated with an Introduction by David Magarshack); pp. 148-150 [(NOTES FROM THE UNDERGROUND) PART I–UNDERGROUND)/(Chapter) IX]: I agree that man is above all a creative animal, condemned consciously to strive towards a goal and to occupy himself with the art of engineering, that is, always and incessantly clear with a path for himself wherever it may lead. And I should not be at all surprised if that were not the reason why he sometimes cannot help wishing to turn aside from the path just because he is condemned to clear it, and perhaps, too, because, however stupid the plain man of action may be as a rule, the thought will sometimes occur to him that the path almost always seems to lead nowhere in particular, and that the important point is not where it leads but that it should lead somewhere, and that a well-behaved child, disdaining the art of engineering, should not indulge in the fatal idleness which, as we all know, is the mother of all vices. Man likes to create and to clear paths--that is undeniable. But why is he also so passionately fond of destruction and chaos? Tell me that. But, if you don’t mind, I’d like to say a few words about that myself. Is he not perhaps so fond of destruction and chaos (and it cannot be denied that he is sometimes very fond of it--that is a fact) because he is instinctively afraid of reaching the goal and completing the building he is erecting? How do you know, perhaps he only loved the building from a distance and not by any means at close quarters; perhaps he only loved building it and not living in it, preferring to leave it later aux animaux domestiques, such as ants, sheep, etc., etc. Now, ants are quite a different matter. They have one marvellous building of this kind, a building that is for ever indestructible--the ant-hill.

The excellent ants began with the ant-hill and with the ant-hill they will most certainly end, which does great credit to their steadfastness and perseverance. But man is a frivolous and unaccountable creature, and perhaps, like a chess-player, he is only fond of the process of achieving his aim, but not of the aim itself. And who knows (it is impossible to be absolutely sure about it), perhaps the whole aim mankind is striving to achieve on earth merely lies in this incessant process of achievement, or (to put it differently) in life itself, and not really in the attainment of any goal, which, needless to say, can be nothing else but twice-two-makes-four, that is to say, a formula; but twice-two-makes-four is not life, gentlemen. It is the beginning of death. At least, man seems always to have been afraid of this twice-two-makes-four, and I am afraid of it now. Let us assume that man does nothing but search for this twice-two-makes-four, sails across oceans and sacrifices his life in this search; but to succeed in his quest, really to find what he is looking for, he is afraid--yes, he really seems to be afraid of it. For he feels that when he has found it there will be nothing more for him to look for. When workmen have finished their work they at least receive their wages, and they go to a pub and later find themselves in a police cell--well, there’s an occupation for a week. But where can man go? At all events, one observes a certain awkwardness about him every time he achieves one of these aims. He loves the process of achievement but not achievement itself, which, I’m sure you will agree, is very absurd. In a word, man is a comical creature; I expect there must be some sort of jest hidden in it all. But twice-two-makes-four is for all that a most insupportable thing. Twice-two-makes-four is, in my humble opinion, nothing but a piece of impudence. Twice-two-makes-four is a farcical, dressed-up fellow who stands across your path with arms akimbo and spits at you. Mind you, I quite agree that twice-two-makes-four is a most excellent thing; but if we are to give everything its due, then twice-two-makes-five is sometimes a most charming little thing, too.

pp. 120-121 (CHAPTER II): Tell me this: why did it invariably happen that just at those moments--yes, at those very moments--when I was acutely conscious of “the sublime and beautiful,” as we used to call it in those days, I was not only conscious but also guilty of the most contemptible actions which--well, which, in fact, everybody is guilty of, but which, as though on purpose, I only happened to commit when I was most conscious that they ought not to be committed? The more conscious I became of goodness and all that was “sublime and beautiful,” the more deeply did I sink into the mire and the more ready I was to sink into it altogether. And the trouble was that all this did not seem to happen to me by accident, but as though it couldn’t possibly have happened otherwise. As though it were my normal condition, and not in the least a disease or a vice, so that at last I no longer even attempted to fight against this vice. It ended by my almost believing (and perhaps I did actually believe) that this was probably my normal condition. At first, at the very outset, I mean, what horrible agonies I used to suffer in that struggle! I did not think others had the same experience, and afterwards I kept it to myself as though it were a secret. I was ashamed (and quite possibly I still am ashamed); it got so far that I felt a sort of secret, abnormal, contemptible delight when, on coming home on one of the foulest nights in Petersburg, I used to realise intensely that again I had been guilty of some particularly dastardly action that day, and that once more it was no earthly use crying over spilt milk; and inwardly, secretly, I used to go on nagging myself, worrying myself, accusing myself, till at last the bitterness I felt turned into a sort of shameful, damnable sweetness, and finally, into real, positive delight! Yes, into delight. Into delight! I’m certain of it. As a matter of fact, I’ve mentioned this because I should like to know for certain whether other people feel the same sort of delight. Let me explain it to you. The feeling of delight was there just because I was so intensely aware of my own degradation; because I felt myself that I had come up against a blank wall; that no doubt, it was bad, but that it couldn’t be helped; that there was no escape, and that I should never become a different man; that even if there still was any time or faith left to make myself into something different, I should most likely have refused to do so; and even if I wanted to I should still have done nothing, because as a matter of fact there was nothing I could change into. And above all – and this is the final point I want to make – whatever happened, happened in accordance with the normal and fundamental laws of intensified consciousness and by a sort of inertia which is a direct consequence of those laws, and that therefore you not only could not change yourself, but you simply couldn’t make any attempt to.

p. 125 [Chapter III]: For forty years it will continuously remember its injury to the last and most shameful detail, and will, besides add to it still more shameful details, worrying and exciting itself spitefully with the aid of its own imagination. It will be ashamed of its own fancies, but it will nevertheless remember everything, go over everything with the utmost care, think up all sorts of imaginary wrongs on the pretext that they, too, might have happened, and will forgive nothing. Quite likely it will start avenging itself, but, as it were, by fits and starts, in all sorts of trivial ways, from behind the stove, incognito, without believing in its right to avenge itself, nor in the success of its vengeance, and knowing beforehand that it will suffer a hundred times more itself from all its attempts at revenge than the person on whom it is revenging itself, who will most probably not care a hang about it. Even on its deathbed it will remember everything with the interest accumulated during all that time, and....And it is just in that cold and loathsome half-despair and half-belief--in that conscious burying oneself alive for grief for forty years--in that intensely perceived, but to some extent uncertain, helplessness of one’s position--in all that poison of unsatisfied desires that have turned inwards--in that fever of hesitations, firmly taken decisions, and regrets that follow almost instantaneously upon them--that the essence of that delight I have spoken of lies.

pp. 130-131 [Chapter V]: I used to get into awful trouble on such occasions though I was not even remotely to be blamed for anything. That was the most horrible part of it. But every time that happened, I used to be touched to the very depth of my soul, I kept on repeating how sorry I was, shedding rivers of tears, and of course deceiving myself, though I was not pretending at all. It was my heart that somehow was responsible for all that nastiness....Here one could not blame even the laws of nature, though the laws of nature have, in fact, always and more than anything else caused me infinite worry and trouble all through my life. It is disgusting to call to mind all this, and as a matter of fact it was a disgusting business even then. For after a minute or so I used to realise bitterly that it was all a lie, a horrible lie, a hypocritical lie, I mean, all those repentances, all those emotional outbursts, all those promises to turn over a new leaf. And if you ask why I tormented myself like that, the answer is because I was awfully bored sitting about and doing nothing, and that is why I started on that sort of song and dance. I assure you it is true. You’d better start watching yourselves more closely, gentlemen, and you will understand that it is so. I used to invent my own adventures, I used to devise my own life for myself, so as to be able to carry on somehow. How many times, for instance, used I to take offence without rhyme or reason, deliberately; and of course I realised very well that I had taken offence at nothing, that the whole thing was just a piece of play-acting, but in the end I would work myself up into such a state that I would be offended in good earnest. All my life I felt drawn to play such tricks, so that in the end I simply lost control of myself. Another time I tried hard to fall in love. This happened to me twice, as a matter of fact. And I can assure you, gentlemen, I suffered terribly. In my heart of hearts, of course, I did not believe that I was suffering, I’d even sneer at myself in a vague sort of way, but I suffered agonies none the less, suffered in the most genuine manner imaginable, as though I were really in love. I was jealous. I made scenes. And all because I was so confoundedly bored, gentlemen, all because I was so horribly bored. Crushed by doing nothing. For the direct, the inevitable, and the legitimate result of consciousness is to make all action impossible, or--to put it differently--consciousness leads to thumb-twiddling.

DOSTOYEVSKY: An Examination of the Major Novels by Richard Peace; pp. 165-167 [6-The Pamphlet Novel: ‘The Devils’]: But at the literary fete, even though elements of comedy are still strongly present, Stepan Trofimovich proclaims the same idea with the urgency and stridency of a man explaining a fundamental article of faith; the primacy of the aesthetic is now to be taken seriously:

‘But I declare that Shakespeare and Raphael are higher than the Emancipation of the Serfs; higher than the concept of nationality; higher than socialism; higher than the younger generation; higher than chemistry; higher, almost, than the whole of mankind; for they are indeed the fruit, the real fruit of the whole of mankind, perhaps, the highest fruit that ever can be. Beauty’s form already achieved, without the achievement of which, I would perhaps not even agree to live...Good Lord!’ he cried throwing up his arms. ‘Ten years ago I shouted exactly the same from a stage in St Petersburg, exactly the same thing, in the very same words, and just like you, they did not understand anything, but laughed and hissed as you are doing now. Dull-witted people, what do you need to enable you to comprehend? Do you know, do you know that humanity could get along without Englishmen, could get along without Germany, and, of course, without the Russians. It could get along without science, without bread, but only one thing, and one thing alone, it could not get on without, and that is beauty; for there would be nothing to do on earth. All mystery is here; all history is here. Science itself could not last a moment without beauty. Do you know this, you who laugh? It would turn into clumsy philistinism. You would not be able to invent a nail!...I shall not yield!’ He yelled absurdly by way of conclusion, and banged his fist on the table with all his might.

(Pt III, Ch. I, 4)

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

(as per tcaudilllg)

(as per tcaudilllg)