Sylvia Plath

Gamma SF (Se-ISFj or Se-ESFp); Delta NF (Ne-INFj or Ne-ENFp); or IEI [someone once suggested that she V.I.'d INFp]

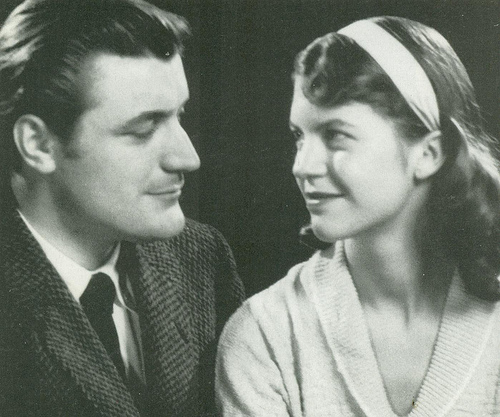

Here are the pictures:

http://blogs.heraldo.es/dereojo/wp-c...plath-nino.jpg

http://patrishka.files.wordpress.com...1950.jpg?w=621

http://www.sylviaplath.de/pic/plath2.gif

http://thebutterflydiaries.files.wor...photograph.jpg

http://transom.org/wp/wp-content/upl...lvia_plath.jpg

http://www.annestahl.com/thesis/images/plath.jpg

http://silencedmajority.blogs.com/.a...72ae970b-800wi

http://patrishka.files.wordpress.com...edith-1956.jpg

http://www.sheilaomalley.com/archives/sylvia5.jpg

http://www.sheilaomalley.com/archives/sylvia4.jpg

http://patrishka.files.wordpress.com...via-plath.jpeg

http://i.dailymail.co.uk/i/pix/2009/...85_468x345.jpg

http://www.thebuzzmedia.com/wp-conte...ach-bikini.jpg

http://www.notablebiographies.com/im...08_img0556.jpg

http://lh6.ggpht.com/_8Z3s3ZJmwDk/S9...ia-plath-1.jpg

http://www.sylviaplathforum.com/images/sp-th.jpg

http://media.nowpublic.net/images//d...6ee9a44c80.jpg

http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/03/01/home/plath.jpg

Here are the quotes:

- from Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems [Edited by Ted Hughes]; p. 162:

I Am Vertical

But I would rather be horizontal.

I am not a tree with my root in the soil

Sucking up minerals and motherly love

So that each March I may gleam into leaf,

Nor am I the beauty of a garden bed

Attracting my share of Ahs and spectacularly painted,

Unknowing I must soon unpetal.

Compared with me, a tree is immortal

And a flower-head not tall, but more startling,

And I want the one’s longevity and the other’s daring.

Tonight, in the infinitesimal light of the stars,

The trees and flowers have been strewing their cool odors.

I walk among them, but none of them are noticing.

Sometimes I think that when I am sleeping

I must most perfectly resemble them –

Thoughts gone dim.

It is more natural to me, lying down.

Then the sky and I are in open conversation,

And I shall be useful when I lie down finally:

Then the trees may touch me for once, and the flowers have time for me.

28 March 1961

- from Sylvia Plath: A Literary Life by Linda Wagner-Martin; pp. 78-79: As it is, here in the spring of 1961, the poem she wrote just ten days after "In Plaster" and "Tulips" comes the closest to effecting some sense of rest for the persona. Still an inordinately dark poem, "I Am Vertical" takes its first line as title, pairing it with "But I would rather be horizontal." In draft, the first line of this poem was the flat-footed "This upright position is unnatural / I am not a tree with my root in the soil / sucking up minerals and motherly love"; whereas Plath keeps lines two and three, her new beginning makes them metaphoric rather than literal.

It is in the second stanza of the moving poem that Plath seems to locate a sense of peace, a calm that - even if it is not exactly health - bodes well for harmony. Almost mystically, the persona identifies with the trees and flowers, and the stanza opens with a languid meditation: "Tonight, in the infinitesimal light of the stars, / The trees and flowers have been strewing their cool odors. / I walk among them . . ."

An early title for the poem was the descriptive "In a Midnight Garden." Associations with the Garden of Eden, with the power of the myth of creation to form man and woman, and with the healing images of darkness might have created a very different tone for this work. Plath, however, abandons this title and with it more acceptable poetic associations, in order to give the reader this colder, more realistic insight. The reader thinks of Mrs. Plath's [Sylvia's mother] late comment, "she [Sylvia] was so exhausted. She carried so much . . . Ted expected so much of her. She took care of the bills, she made out the tax report, she did all the correspondence because he never would attend to it."

Still located in a sympathetic natural surrounding, the persona moves into a confessional moment, remarking that she is happiest when she sleeps, with "thoughts gone dim." Such an image sounds like the reaction of the fatigued "Tulips" persona. Yet here the final quatrain of the poem expresses what might be a healthful, peaceful stasis for her: "It is more natural to me, lying down. / Then the sky and I are in open conversation, / And I shall be useful when I lie down finally: / Then the trees may touch me for once, and the flowers have time for me."

The poet works through metaphor, challenging the reader not to correct that last set of images. We want Plath to say that she will touch the trees; she will have time for the flowers. But, being a poet and being intrinsically aware of the power of language to express without always revealing, she says something quite different. She says in effect, that health is beyond her power to achieve, and that consummation will reclaim her for the only world that matters, the natural one.

- from BITTER FAME: A Life of Sylvia Plath by Anne Stevenson; p. 54 [(Chapter) 3 – The City of Spare Parts, 1952-1955]: Sylvia began work on her honors thesis, a study of the double in Dostoevsky, shortly after she returned to Smith in September. “The Magic Mirror” – appropriately titled – is a detached, competent study of the crisis of identity in nineteenth-century romantic fiction, which in many ways anticipated the schizoid diagnoses of twentieth-century psychoanalysis. Unfortunately, Sylvia adopted for her thesis the wooden, academic style approved by her supervisor, and no one would guess from reading it that the author of this well-mannered, well-researched academic paper had invested the least bit of emotional capital in it. The logic is impeccable, the notes impressive, the writing studious.

- p. v: There was a tremendous power in the burning look of her dark eyes; she came “conquering and to conquer.” She seemed proud and occasionally even arrogant; I don’t know if she ever succeeded in being kind, but I do know that she badly wanted to and that she went through agonies to force herself to be a little kind. There were, of course, many fine impulses and a most commendable initiative in her nature; but everything in her seemed to be perpetually seeking its equilibrium and not finding it; everything was in chaos, in a state of agitation and restlessness. Perhaps the demands she made upon herself were too severe and she was unable to find in herself the necessary strength to satisfy them.

-- Dostoevsky, The Devils

- from The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath; pp. 160-161 (Chapter Thirteen): Then I saw my father’s gravestone.

It was crowded right up by another gravestone, head to head, the way people are crowded in a charity ward when there isn’t enough space. The stone was of a mottled pink marble, like tinned salmon, and all there was on it was my father’s name and, under it, two dates, separated by a little dash.

At the foot of the stone I arranged the rainy armful of azaleas I had picked from a bush at the gateway of the graveyard. Then my legs folded under me, and I sat down in the sopping grass. I couldn’t understand why I was crying so hard.

Then I remembered that I had never cried for my father’s death.

My mother hadn’t cried either. She had just smiled and said what a merciful thing it was for him he had died, because if he had lived he would have been crippled and an invalid for life, and he couldn’t have stood that, he would rather have died than had that happen.

I laid my face to the smooth face of the marble and howled my loss into the cold salt rain.

- Sylvia Plath: A Biography by Connie Ann Kirk pp. 145-147 [(Chapter) 5. A Disturbance in Mirrors: The Late Poems (STASIS AND PROCESS: THE BEEHIVE)]: For, though the derivation of the bee imagery is mythical, Plath is careful to place the image of the beehive within a social context. She does this most systematically through the stages she traces in these poems of the relationship between the poet, the beehive, and the beekeeper. She moves from her father as beekeeper in the three pre-Ariel bee poems to an image of the village midwife as beekeeper and finally to herself as beekeeper in Ariel. Thus a complex set of identifications between the bees and herself and a complex set of oppositions between the bees and an essentially patriarchal human world is set up; also suggested are a number of ways in which the metaphor of the beehive relates to the larger context of a capitalist society.

Sylvia's Plath's father, Otto Plath, a professor of biology at Boston University and a recognized authority on bees, published Bumblebees and Their Ways in 1934, two years after Sylvia was born. In three early poems -- "Lament" (1951-52), "Electra on Azalea Path" (1959), and "The Beekeeper's Daughter" (1959) -- Plath directs the symbolic significance of the bees and the beehive toward her relationship with her father. In "Lament," an awkward early poem, her father is described as a god-like figure oblivious to storm, sea and lightning, who was nevertheless and ludicrously struck down by a swarm of bees. "A scowl of sun struck down my mother, / tolling her grave with golden gongs, / but the sting of bees took away my father." By the time she writes the two 1959 poems, Plath has begun to identify herself with the bees and thus somehow to assign herself guilt for her father's death, even though she says, in the opening stanza of "Electra on Azalea Path," "I had nothing to do with guilt or anything." "Electra on Azalea Path" begins by identifying the speaker of the poem with a hive of wintering bees. "The day you died I went into the dirt / . . . Where bees, striped black and gold, sleep out the blizzard / Like hieratic stones," she says, and, "It was good for twenty years, that wintering -- ." Somehow, she implies in this poem, it was her birth that presaged her father's death, and her love which finally killed him. Her assumption of guilt is clear in the poem's end: "O pardon the one who knocks for pardon at / Your gate, father -- your hound-bitch, daughter, friend. / It was my love that did us both to death."

Plath built up a mythical temporal schema into which she fit what she saw as the significant events in her life. Thus she says in "Lady Lazarus" of her suicide attempts, "I have done it again. / One year in every ten / I manage it -- ." Her first suicide attempt was at age twenty, during the summer of 1953, and she worked backward and forward from this center. She sometimes says she was ten when her father died, but actually she had just turned eight years old when he died on November 2, 1940. Her birthday is October 27, and her father was dying then, so it is not strange that an eight-year-old would connect the two events and feel a certain guilt. Especially since, as Plath suggests in a number of places including "Electra on Azalea Path," her mother quite naturally tried to soften the loss to her children: "My mother said; you died like any man. / How shall I age into that state of mind?" To an eight-year-old child, who felt the loss of her father but didn't quite understand it, his disappearance followed by what might have seemed a conspiracy of silence would have been both strange and suspicious. Why was no one saying anything to her about her father? Was it because his death was somehow her fault? [49. In 1954 Plath described to a friend her reaction to her father's death. "He was an autocrat. I adored and despised him, and I probably wished many times that he were dead. When he obliged me and died, I imagined that I had killed him." Quoted in Nancy Hunter Steiner, A Closer Look at Ariel: A Memory of Sylvia Plath (New York: Harper's Magazine Press, 1973); p. 45.] In any case, Plath makes her father's death fall a third of the way through her life, and her own first suicide attempt marks the second third. That her final and successful suicide attempt came at age thirty does suggest that to some extent she became caught up in her own systematizing. Of course, the actual reasons for seeing suicide as a solution go far beyond what some readers of Plath's poetry have been tempted to call a need to reenact in life what one has structured in art.

- from Sylvia Plath: A Literary Life by Linda Wagner-Martin; pp. 110-111: Plath's neatly-typed letters throughout her marriage are illustrative of that well-regulated behavior. Whether she was writing to Theodore Roethke about a possible teaching post for Hughes, even though it was Plath herself who was so moved by Roethke's poetry, or to John Lehmann with submissions for both of them to London Magazine, or to Brian Cox about Critical Quarterly, she appeared to be the tidy and competent secretary she had so feared becoming. Unfortunately, as we have seen, some of her earlier poems gave off the same aura of starched neatness -- with any recognizable emotion kept at a distance. The truly dramatic changes between those college-era poems, like "Circus in Three Rings" and "Two Lovers and a Beachcomber by the Real Sea," and such late poems as "Applicant," "Purdah," and "Lady Lazarus," were both shocking and inexplicable.

- from A Disturbance in Mirrors by Pamela J. Annas; pp. 109-110 [The Late Poems]: This dual consciousness of self, the perception of self as both subject and object, is characteristic of the literature of marginalized or oppressed classes. It is characteristic of proletarian writers in their (admittedly sometimes dogmatic) perception of their own relation to a decadent past, a dispossessed present, and a utopian future. It is characteristic of black American writers. W.E.B. DuBois makes a statement very similar in substance to Jameson's in The Souls of Black Folk, and certainly the basic existential condition of Ellison's invisible man is his dual consciousness, which only toward the end of that novel becomes a means to freedom of action rather than paralysis. It is true of contemporary women writers, such novelists as Doris Lessing, Margaret Atwood, and Maxine Hong Kingston, and of such poets as Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, and Marge Piercy. In some sense it is more a long-standing characteristic of American literature than of any other major world literature, for each immigrant group, however great its desire for assimilation into the American power structure, at least initially possessed this dual consciousness. Finally, a dialectical perception of self as both subject and object, as both worker and commodity, of self in relation to past and future as well as present, is characteristic of revolutionary literature, whether the revolution is primarily political or cultural.

Sylvia Plath has this dialectical awareness of self as both subject and object in particular relation to the society in which she lived. The problem for her, and this is perhaps the problem of Cold War America, is in the second aspect of a dialectical consciousness: an awareness of oneself in significant relation to past and future. The first person narrator of what is probably her best short story, "Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams," is a clerk/typist in a psychiatric clinic who describes herself as a "dream connoisseur," who keeps her own personal record of all dreams which pass through her office, and who longs to look at the oldest record book the Psychoanalytic Institute possesses. "This dream book was spanking new the day I was born," she says, and elsewhere makes the connection even clearer: "the clinic started thirty-three years ago -- the year of my birth oddly enough."* This connection suggests the way in which Plath uses history and views herself in relation to it. The landscape of her late works is a contemporary social landscape. It goes back in time to encompass such significant historical events as the Rosenberg trial and execution -- around which the opening chapter of The Bell Jar is structured -- and of course it encompasses, is perhaps obsessed with, the major historical event of her time, the Second World War. But social history, reference to actual historical events, seems to stop for Plath where her own life starts, and is replaced at that point by a mythic timeless past populated by creatures from folk tale, fairy tale and classical mythology. This is not surprising, since as a woman she had scant affirmation of her part in shaping history. Why should she feel any relation to it? But more crucially, there is in Sylvia Plath's work no imagination of the future, no utopian or even anti-utopian consciousness. There is a dialectical consciousness in her poetry of the self as simultaneously object and subject, but she was unable to develop in her particular social context a consciousness of herself in relation to a past and future beyond her own lifetime.

* Sylvia Plath, "Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams," in Sylvia Plath: Johnny Panic and The Bible of Dreams/Short Stories, Prose, and Diary Excerpts (New York: Harper & Row, 1978), pp. 153, 159. First published in Atlantic (September 1968), pp. 54-60.

- from A Disturbance in Mirrors: The Poetry of Sylvia Plath by Pamela J. Annas; pp. 104-105:

While a painfully acute sense of the depersonalization and fragmentation of 1950s America is characteristic of the late poems, three of them describe particularly well the social landscape within which the "I" of Sylvia Plath's poems is trapped: "The Applicant," "Cut," and "The Munich Mannequins." ["The Social Context" was originally published in slightly different form as "The Self in the World: The Social Context of Sylvia Plath's Late Poems" in Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 7, nos. 1/2 (Winter 1980), pp. 171-83. Reprinted in Linda Wagner, ed., Critical Essays on Sylvia Plath (Boston: L. K. Hall, 1984), pp. 130-39.] The recurring metaphors of fragmentation and reification -- the abstraction of the individual -- in Plath's late poetry are socially and historically based. They are images of Nazi concentration camps, of "fire and bombs through the roof" ("The Applicant"), of cannons, of trains, of "wars, wars, wars" ("Daddy"). They are images of kitchens, iceboxes, adding machines, typewriters, and the depersonalization of hospitals. The sea and the moon are still central images, but in the poems from 1961 on they take on a harsher quality. "The moon, also, is merciless," Plath writes in "Elm."

One of the more bitter poems in Ariel is "The Applicant" (October 11, 1962), a portrait of marriage in contemporary western culture. However, the "courtship" and "wedding" in the poem seem to represent not only male/female relations but human relations in general. That the applicant also can be seen as applying for a job or buying a product suggests a close connection between the capitalist economic system, the patriarchal family structure, and the general depersonalization of human relations. Somehow all interaction between people, and especially that between men and women, given the history of the use of women as items of barter, is conditioned by the ethics and assumptions of a bureaucratized market place. However this system got started, both men and women are implicated in its perpetuation. As in many of Plath's poems, one feels in reading "The Applicant" that Plath sees herself and her imaged personae as not merely caught in -- victims of -- this situation, but in some sense culpable as well. In "The Applicant," the poet is speaking directly to the reader, addressed as "you" throughout. So we, too, are implicated, for we are also potential "applicants."

In the first stanza of "The Applicant," as in the beginning of "Event" (May 21, 1962), people are described as crippled and as dismembered pieces of bodies. Thus the theme of dehumanization begins the poem. Moreover, the pieces described here are not even flesh, but "a glass eye, false teeth or a crutch, / A brace or a hook, / Rubber breasts or a rubber crotch." We are already so implicated in a sterile and machine-dominated culture that we are likely part artifact and sterile ourselves. One is reminded of the "clean pink plastic limb" which the surgeon in "The Surgeon at 2 A.M." complacently attaches to his patient. One is also reminded of Chief Bromden's conviction, in Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, written at about the same time as "The Applicant," that those people who are integrated into society are just collections of wheels and cogs, smaller replicas of a smoothly functioning larger social machine. "The ward is a factory for the Combine," Bromden thinks, "something that came all twisted different is now a functioning, adjusted component, a credit to the whole outfit and a marvel to behold. Watch him sliding across the land with a welded grin." [Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (New York: Viking Press, 1962), p. 38]

In stanza two of "The Applicant," Plath describes the emptiness which characterizes the applicant and which is another version of the roboticized activity of Kesey's Adjusted Man. Are there "stitches to show something's missing?" she asks. The applicant's hand is empty, so she provides "a hand"

To fill it and willing

To bring teacups and roll away headaches

And do whatever you tell it.

Will you marry it?

- from Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems (Edited by Ted Hughes); p. 118 [The Beekeeper’s Daughter (1959)]:

The Beekeeper’s Daughter

A garden of mouthings. Purple, scarlet-speckled, black

The great corollas dilate, peeling back their silks.

Their musk encroaches, circle after circle,

A well of scents almost too dense to breathe in.

Hieratical in your frock coat, maestro of the bees,

You move among the many-breasted hives,

My heart under your foot, sister of a stone.

Trumpet-throats open to the beaks of birds.

The Golden Rain Tree drips its powders down.

In these little boudoirs streaked with orange and red

The anthers nod their heads, potent as kings

To father dynasties. The air is rich.

Here is a queenship no mother can contest—

A fruit that’s death to taste: dark flesh, dark parings.

In burrows narrow as a finger, solitary bees

Keep house among the grasses. Kneeling down

I set my eye to a hole-mouth and meet an eye

Round, green, disconsolate as a tear.

Father, bridegroom, in this Easter egg

Under the coronal of sugar roses

The queen bee marries the winter of your year.

- from The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath & Ted Hughes by Janet Malcolm; pp. 7-8 [Part One]: Life, as we all know, does not reliably offer – as art does – a second (and a third and a thirtieth) chance to tinker with a problem, but Ted Hughes’s history seems to be uncommonly bare of the moments of mercy that allow one to undo or redo one’s actions and thus feel that life isn’t entirely tragic. Whatever Hughes might have undone or redone in his relationship to Sylvia Plath, the opportunity was taken from him when she committed suicide, in February of 1963, by putting her head in a gas oven as her two small children slept in a bedroom nearby, which she had sealed against gas fumes, and where she had placed mugs of milk and a plate of bread for them to find when they awoke. Plath and Hughes were not living together at the time of her death. They had been married for six years – she was thirty and he was thirty-two when she died – and had separated the previous fall in a turbulent way. There was another woman. It is a situation that many young married couples find themselves in – one that perhaps more couples find themselves in than don’t – but it is a situation that ordinarily doesn’t last: the couple either reconnects or dissolves. Life goes on. The pain and bitterness and exciting awfulness of sexual jealousy and sexual guilt recede and disappear. People grow older. They forgive themselves and each other, and may even come to realize that what they are forgiving themselves and each other for is youth.

But a person who dies at thirty in the middle of a messy separation remains forever fixed in the mess. To the readers of her poetry and her biography, Sylvia Plath will always be young and in a rage over Hughes’s unfaithfulness. She will never reach the age when the tumults of young adulthood can be looked back upon with rueful sympathy and without anger and vengefulness.

- from A Disturbance in Mirrors: The Poetry of Sylvia Plath by Pamela J. Annas; p. 5 [Reflections]:

Plath’s fascination with mirror imagery began early and consciously, perhaps as a way of imaging her own ambivalence and sense of division. Her senior honors thesis at Smith College, written in 1954-1955, the year following her suicide attempt and recovery, was called “The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoevsky’s Novels.” In the introduction, she writes:

the appearance of the Double is an aspect of man’s eternal desire to solve the enigma of his own identity. By seeking to read the riddle of his soul in its myriad manifestations, man is brought face to face with his own mysterious mirror image, an image which he confronts with mingled curiosity and fear. This simultaneous attraction and repulsion arises from the inherently ambivalent nature of the Double, which may embody not only good, creative characteristics, but also evil, destructive ones. [1. Sylvia Plath “The Magic Mirror,” from the Sylvia Plath manuscript collection, The Lilly Library, Indiana University, p. 1.]

After discussing examples of the double in Poe, Stevenson, and Wilde, she remarks: “The confrontation of the Double in these instances usually results in a duel which ends in insanity or death for the original hero.” [2. Ibid., p. 2.] Plath bases her study of the image of the double in Dostoevsky on Otto Rank’s work and other investigations into the schizophrenic personality. Her discussion of motifs in The Double might be a prescient description of motifs in her own subsequent poetry; she writes that the motifs that “illustrate Godyakin’s dilemma . . . include the repetition of mirror imagery, identification with animals, and a simultaneous fear of murder and desire for death.” [3. Ibid., p. 7.] Plath concludes her 60-pages thesis with these remarks:

It is Godyakin’s inability to acknowledge his inner conflict and Ivan’s inability to reconcile his inner conflict which result in severe schizophrenia for both. . . . Dostoevsky implies that recognition of our various mirror images and reconciliation with them will save us from disintegration. This reconciliation does not mean a simple or monolithic resolution of conflict, but rather a creative acknowledgement of the fundamental duality of man; it involves a constant courageous acceptance of the eternal paradoxes within the universe and within ourselves. [4. Ibid., pp. 59-60.]

- from Ariel: The Restored Edition (A Facsimile of Plath’s Manuscript, Reinstating Her Original Selection and Arrangement by Sylvia Plath [Foreword by Frieda Hughes]; pp. 29-30 [Ariel and other poems]:

The Night Dances

A smile fell in the grass.

Irretrievable!

And how will your night dances

Lose themselves. In mathematics?

Such pure leaps and spirals—

Surely they travel

The world forever, I shall not entirely

Sit emptied of beauties, the gift

Of your small breath, the drenched grass

Smell of your sleeps, lilies, lilies.

Their flesh bears no relation.

Cold folds of ego, the calla,

And the tiger, embellishing itself –

Spots, and a spread of hot petals.

The comets

Have such a space to cross,

Such coldness, forgetfulness.

So your gestures flake off—

Warm and human, then their pink light

Bleeding and peeling

Through the black amnesias of heaven.

Why am I given

These lamps, these planets

Falling like blessings, like flakes

Six-sided, white

On my eyes, my lips, my hair

Touching and melting.

Nowhere.

- from Sylvia Plath: A Biography by Linda Wagner-Martin; p. 88: Some of Norton's reading complemented hers: they both liked Salinger's Catcher in the Rye and Lawrence's Women in Love. But Dick also enjoyed contradicting Sylvia, as when he wrote a scathing parody of one of her favorite authors, Virginia Woolf.

- from The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath; pp. 65-69 (Chapter Six): Then we kissed and hugged a while and I felt a little better. I drank the rest of the Dubonnet and sat cross-legged at the end of Buddy’s bed and asked for a comb. I began to comb my hair down over my face so Buddy couldn’t see it. Suddenly I said, ‘Have you ever had an affair with anyone, Buddy?’

I don’t know what made me say it, the words just popped out of my mouth. I never thought for one minute that Buddy Willard would have an affair with anyone. I expected him to say, ‘No, I have been saving myself for when I get married to somebody pure and a virgin like you.’

But Buddy didn’t say anything, he just turned pink.

‘Well, have you?’

‘What do you mean, an affair?’ Buddy asked then in a hollow voice.

‘You know, have you ever gone to bed with anyone?’ I kept rhythmically combing the hair down over the side of my face nearest to Buddy, and I could feel the little electric filaments clinging to my hot cheeks and I wanted to shout, ‘Stop, stop, don’t tell me, don’t say anything.’ But I didn’t, I just kept still.

‘Well, yes, I have,’ Buddy said finally.

I almost fell over. From the first night Buddy Willard kissed me and said I must go out with a lot of boys, he made me feel I was much more sexy and experienced than he was and that everything he did like hugging and kissing and petting was simply what I made him feel like doing out of the blue, he couldn’t help it and didn’t know how it came about.

Now I saw he had only been pretending all this time to be so innocent.

‘Tell me about it,’ I combed my hair slowly over and over, feeling the teeth of the comb dig into my cheek at every stroke. ‘Who was it?’

Buddy seemed relieved I wasn’t angry. He even seemed relieved to have somebody to tell about how he was seduced.

Of course, somebody had seduced Buddy, Buddy hadn’t started it and it wasn’t really his fault. It was this waitress at the hotel he worked at as a busboy the last summer on Cape Cod. Buddy had noticed her staring at him queerly and shoving her breasts up against him in the confusion of the kitchen, so finally one day he asked her what the trouble was and she looked him straight in the eye, and said, ‘I want you.’

‘Served up with parsley?’ Buddy had laughed innocently.

‘No,’ she had said. ‘Some night.’

And that’s how Buddy had lost his pureness and his virginity.

At first I thought he must have slept with the waitress only the once, but when I asked how many times, just to make sure, he said he couldn’t remember but a couple of times a week for the rest of the summer. I multiplied three by ten and got thirty, which seemed beyond all reason.

After that something in me just froze up.

Back at college I started asking a senior here and a senior there what they would do if a boy they knew suddenly told them he’d slept thirty times with some slutty waitress one summer, smack in the middle of knowing them. But these seniors said most boys were like that and you couldn’t honestly accuse them of anything until you were at least pinned or engaged to be married.

Actually, it wasn’t the idea of Buddy sleeping with somebody that bothered me. I mean I’d read about all sorts of people sleeping with each other, and if it had been any other boy I would merely have asked him the most interesting details, and maybe gone out and slept with somebody myself just to even things up, and then thought no more about it.

What I couldn’t stand was Buddy’s pretending I was so sexy and he was so pure, when all the time he’d been having an affair with that tarty waitress and must have felt like laughing in my face.

‘What does your mother think about this waitress?’ I asked Buddy that week-end.

Buddy was amazingly close to his mother. He was always quoting what she said about the relationship between a man and a woman, and I knew Mrs Willard was a real fanatic about virginity for men and women both. When I first went to her house for supper she gave me a queer, shrewd, searching look, and I knew she was trying to tell whether I was a virgin or not.

Just as I thought, Buddy was embarrassed. ‘Mother asked me about Gladys,’ he admitted.

‘Well, what did you say?’

‘I said Gladys was free, white and twenty-one.’

Now I knew Buddy would never talk to his mother as rudely as that for my sake. He was always saying how his mother said, ‘What a man wants is a mate and what a woman wants is infinite security,’ and, ‘What a man is is an arrow into the future and what a woman is is the place the arrow shoots off from,’ until it made me tired.

Every time I tried to argue, Buddy would say his mother still got pleasure out of his father and wasn’t that wonderful for people their age, it must mean she really knew what was what.

Well, I had just decided to ditch Buddy Willard for once and for all, not because he’d slept with that waitress but because he didn’t have the honest guts to admit it straight off to everybody and face up to it as part of his character, when the phone in the hall rang and somebody said in a little knowing singsong, ‘It’s for you, Esther, it’s from Boston.’

I could tell right away something must be wrong, because Buddy was the only person I knew in Boston, and he never called me long distance because it was so much more expensive than letters. Once, when he had a message he wanted me to get almost immediately, he went all round his entry at medical school asking if anybody was driving up to my college that weekend, and sure enough, somebody was, so he gave them a note for me and I got it the same day. He didn’t even have to pay for a stamp.

It was Buddy all right. He told me that the annual fall chest X-ray showed he had caught TB and he was going off on a scholarship for medical students who caught TB to a TB place in the Adirondacks. Then he said I hadn’t written since that last week-end and he hoped nothing was the matter between us, and would I please try to write him at least once a week and come to visit him at this TB place in my Christmas vacation?

I had never heard Buddy so upset. He was very proud of his perfect health and was always telling me it was psychosomatic when my sinuses blocked up and I couldn’t breathe. I thought this an odd attitude for a doctor to have and perhaps he should study to be a psychiatrist instead, but of course I never came right out and said so.

I told Buddy how sorry I was about the TB and promised to write, but when I hung up I didn’t feel one bit sorry. I only felt a wonderful relief.

I thought the TB might just be a punishment for living the kind of double life Buddy lived and feeling so superior to people. And I thought how convenient it would be now I didn’t have to announce to everybody at college I had broken off with Buddy and start the boring business of blind dates all over again.

I simply told everyone that Buddy had TB and we were practically engaged, and when I stayed in to study on Saturday nights they were extremely kind to me because they thought I was so brave, working the way I did just to hide a broken heart.

- from Sylvia Plath: A Literary Life by Linda Wagner-Martin; pp. 102-103 (Part Two/(Chapter) 9 – Plath’s Poems about Women]: To be considered along with these autobiographical emphases is the pattern Sandra Gilbert finds that connects “Three Women,” or “Three Voices” as it was originally titled, with the three women characters in Virginia Woolf’s novel, The Waves. With some remarkable similarities between the language of Susan, Rhoda and Jinny and Plath’s three speakers, and with knowledge of the fact that she much admired and loved Woolf’s work, Gilbert’s point is plausible. [28. Sandra M. Gilbert, “In Yeats’ House: The Death and Resurrection of Sylvia Plath,” Critical Essays on Sylva Plath, ed. Linda W. Wagner, pp. 217-18.] It also is comforting to see that a woman writer would turn to another woman writer for imaginative help in creating effective and poetically real female characters. As a composite of Plath’s hospital experience, her reading life, and her own emotional understanding of becoming a mother, “Three Women” is the most impressive long poem Plath had written, or would write.

- pp. 69-70 [Part One/(Chapter) 7 – Defining Health]: Finally, the faceless speaker (brought to the reader’s consciousness in the tautly rhyming two-part line, “I have no face, I have wanted to efface myself”) seems to become in fact the metaphor she had earlier used to express her lack of volition: “a cut-paper shadow.” Ostensibly a poem about recovery and a yearning for health, “Tulips” is filled with contradictory, and disturbing, images. (One recalls Plath’s matter-of-fact journal line, “Writing is my health.”) [2. Sylvia Plath, Journal, p. 164.]

Ted Hughes states in a 1995 essay that the spring of 1961 brought Plath to her real voice (“Tulips” and “In Plaster” were each written March 18, 1961, and were followed ten days later by “I Am Vertical”). His theory is that she had found that voice in 1959, with her writing of the Johnny Panic story, but that the complexities of her life – “change of country, home-building, birth and infancy of her first child” [3. Ted Hughes, “Sylvia Plath’s Collected Poems and The Bell Jar,” Winter Pollen, p. 467.] – interfered so that it was not until 1961 that she was able to resume that voice in her work. Hughes’s focus in this essay is on Plath’s very rapid writing of The Bell Jar, which he claims she wrote much of in the spring of 1961. He comments on what he sees as her recurring theme: “That mythic scheme of violent initiation, in which the old self dies and the new self is born, or the false dies and the true is born, or the child dies and the adult is born, or the base animal dies and the spiritual self is born . . .” [4. Ibid., p. 468.] While he connects this theme with its use in the writing of D. H. Lawrence and Dostoevsky, he also links it with Christianity.

- from Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems [Edited by Ted Hughes]; p. 62 [The Everlasting Monday (1957)]:

The Everlasting Monday

Thou shalt have an everlasting

Monday and stand in the moon.

The moon’s man stands in his shell,

Bent under a bundle

Of sticks. The light falls chalk and cold

Upon our bedspread.

His teeth are chattering among the leprous

Peaks and craters of those extinct volcanoes.

He also against black frost

Would pick sticks, would not rest

Until his own lit room outshone

Sunday’s ghost of sun;

Now works his hell of

Mondays in the moon’s ball,

Fireless, seven chill seas chained to his ankle.

- from Sylvia Plath: A Biography by Connie Ann Kirk; pp. 85-86 [Chapter 4 - THE ACADEMIC LIFE (1950-1955)/RETURN TO SMITH]: In the spring semester of her senior year, 1955, Sylvia went back to Smith early in January and entered the infirmary with a sinus infection that kept her there for a week. During this stay, she wrote five poems and held court with visitors. One of these was a man sent by Alfred Kazin, an editor named Peter Davison from Harcourt, Brace who asked her to keep his publishing house in mind should she ever complete a novel. Before classes began, Sylvia dropped off her thesis to be typed; it was titled "The Magic Mirror: A Study of the Double in Two of Dostoevsky's Novels." Her adviser, Professor Gibian, called it a masterpiece. She also sent out the new poems she had written to the New Yorker. Her classes during her last semester at Smith were: Shakespeare, Intermediate German, Twentieth-Century American Novel, a one-hour independent study in Theory and Practice of Poetics, and Honors hours. Vogue sent her notice that she reached the finals in the Prix de Paris, which meant that she next had to write a ten-page composition on Americana. If anyone thought Sylvia might allow herself an easy last semester of "senioritis," enjoying her youth and last weeks of college by not working quite as hard, they were badly mistaken. She did, however, decide to drop German, which she did not need to graduate, to allow her more time to focus on her writing. Ironically, German was the subject her father had taught many years earlier at Boston College and that her mother once taught in high school.

- from Sylvia Plath: A Literary Life by Linda Wagner-Martin; p. 139 [(Part Two)/12 - Sylvia Plath, The Poet and her Writing Life]: There is some sense in which the fact that Hughes published a collection of her short stories and essays, with his long prefatory introduction, has been limiting. He indicates that Plath's ambition to write short stories for both The New Yorker and The Ladies' Home Journal baffles him; the tone of his essay about her fiction writing suggests that he is also baffled by her even wanting to write prose. [13. Ted Hughes, "Introduction," Johnny Panic, pp. 12-13, 16-18.] But he does not give enough credence to the fact that Plath's continuing model for prose was the fiction of Virginia Woolf, that most poetic of modernists. (As she had written in her journal several years earlier, "What is my voice? Woolfish, alas, but tough.") [14. Sylvia Plath, Journals, p. 186.] For Plath, as for Woolf, there was little difference between a prose paragraph or a long-lined poem stanza. The integrity of the work's rhythm remained the determining principle for organization.

- pp. 117-118: As has been mentioned, Sandra Gilbert links the voice of many of Plath's late poems with the women's voices in The Waves (in connection with Plath's imagery of ascent she describes Rhoda's "ascending" images, for example, and that character's notion of becoming "incandescent"), but she finds a more significant correspondence between Plath's work and the late poems of Yeats, particularly his "To Dorothy Wellesley." There he writes of Wellesley being no "common" woman but rather one awaiting visitation of the "Proud Furies each with her torch on high." Gilbert also cites Yeats' poem "He and She" as a possible source for Plath's repeated phrase "I am I," quoting the lines

She sings as the moon sings:

"I am I, am I;

The greater grows my light

The further that I fly." [32. Sandra M. Gilbert, "In Yeats' House," Critical Essays on Sylvia Plath, pp. 204-22.]

The finishing lines of that sextain - "All creation shivers / With that sweet cry" - are in the poet-persona's voice rather than the woman's. The woman artist, so intent on extending her reach as she confirms her self identity, prompts the imagery of both ascent and light, and suggests some possible reinscription on Plath's part in her poem "Fever 103[degrees]."

- from Sylvia Plath: The Critical Heritage (Edited by Linda W. Wagner); p. 1: In the early 1960s, when her first poetry collection, The Colossus and Other Poems, and her novel, The Bell Jar, appeared, most criticism was highly encouraging. Critics recognized a sure new voice, speaking in tightly wrought patterns and conveying a definite sense of control. The more traditional critics responded to Plath's work with enthusiasm. Plath was obviously a well-educated, disciplined writer who usually avoided the sentimentalities of some female writers. She wrote tidy poems, reminiscent of those by Richard Eberhart, Karl Shapiro, Randall Jarrell, and Richard Wilbur. She wrote fiction -- at least part of The Bell Jar -- with a wry voice somewhat like that of J. D. Salinger. In retrospect, that same taut humor was evident in many of the poems from The Colossus.

- from Sylvia Plath: A Biography by Linda Wagner-Martin; p. 157: Later in the spring [1959], Sylvia took another part-time job, this time as secretary to the head of the Sanskrit Department at Harvard. She relearned speedwriting and took comfort in the regularity of her hours and duties. She also was reading widely: Freud, Faulkner, Tolstoi, Ainu tales, the Bible (especially the Book of Job), lives of saints. She was fascinated by accounts of St. Therese, who was sanctified after receiving visits from the Virgin. Sylvia's notes include a long description of Therese's many influenza-like illnesses with high fevers, her hatred of the cold, her fears before the visitations -- tribulations which had echoes in Plath's own life. They also include a description of the earlier St. Teresa, who founded the Discalced (barefooted) Carmelite order in sixteenth-century Spain, and the nuns' early rising, fasting, meditation, and consistent gaiety (and Teresa's own pragmatic wit and stability).

- from Sylvia Plath: The Critical Heritage (Edited by Linda W Wagner); p. 104: Her second novel, she assured her mother, 'will show that same world as seen through the eyes of health.' Ingratitude was 'not the basis of Sylvia's personality'; the second novel, presumably, would have been one long, ingratiating, fictionalized thank-you note to the world. Of course the publisher is right to publish; but since the persons who may be slightly scorched are still alive, why eight years?

The novel itself is no firebrand. It's a slight, charming, sometimes funny and mildly witty, at moments tolerably harrowing 'first' novel, just the sort of clever book a Smith summa cum laude (which she was) might have written if she weren't given to literary airs. From the beginning our expectations of scandal and startling revelation are disappointed by a modesty of scale and ambition and a jaunty temperateness of tone. The voice is straight out of the 1950's: politely disenchanted, wholesome, yes, wholesome, but never cloying, immediately attractive, nicely confused by it all, incorrigibly truthtelling; in short, the kind of kid we liked then, the best product of our best schools. The hand of Salinger lay heavy on her.

- from Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems (Edited by Ted Hughes); pp. 116-117 [Electra on Azalea Path (1959)]:

Electra on Azalea Path

The day you died I went into the dirt,

Into the lightless hibernaculum

Where bees, striped black and gold, sleep out the blizzard

Like hieratic stones, and the ground is hard.

It was good for twenty years, that wintering --

As if you had never existed, as if I came

God-fathered into the world from my mother's belly:

Her wide bed wore the stain of divinity.

I had nothing to do with guilt or anything

When I wormed back under my mother's heart.

Small as a doll in my dress of innocence

I lay dreaming your epic, image by image.

Nobody died or withered on that stage.

Everything took place in a durable whiteness.

The day I woke, I woke on Churchyard Hill.

I found your name, I found your bones and all

Enlisted in a cramped necropolis,

Your speckled stone askew by an iron fence.

In this charity ward, this poorhouse, where the dead

Crowd foot to foot, head to head, no flower

Breaks the soil. This is Azalea Path.

A field of burdock opens to the south.

Six feet of yellow gravel cover you.

The artificial red sage does not stir

In the basket of plastic evergreens they put

At the headstone next to yours, nor does it rot,

Although the rains dissolve a bloody dye:

The ersatz petals drip, and they drip red.

Another kind of redness bothers me:

The day your slack sail drank my sister's breath

The flat sea purpled like that evil cloth

My mother unrolled at your last homecoming.

I borrow the stilts of an old tragedy.

The truth is, one late October, at my birth-cry

A scorpion stung its head, an ill-starred thing;

My mother dreamed you face down in the sea.

The stony actors poise and pause for breath.

I brought my love to bear, and then you died.

It was the gangrene ate you to the bone

My mother said; you died like any man.

How shall I age into that state of mind?

I am the ghost of an infamous suicide,

My own blue razor rusting in my throat.

O pardon the one who knocks for pardon at

Your gate, father -- your hound-bitch, daughter, friend.

It was my love that did us both to death.

- p. 186 [from Three Women: A Poem for Three Voices (March 1962)]:

I shall meditate upon normality.

I shall meditate upon my little son.

He does not walk. He does not speak a word.

He is still swaddled in white bands.

But he is pink and perfect. He smiles so frequently.

I have papered his room with big roses,

I have painted little hearts on everything.

I do not will him to be exceptional.

It is the exception that interests the devil.

It is the exception that climbs the sorrowful hill

Or sits in the desert and hurts his mother's heart.

I will him to be common,

To love me as I love him,

And to marry what he wants and where he will.

- from Sylvia Plath: A Literary Life by Linda Wagner-Martin; pp. 106-108: Sylvia Plath would have been the first to admit that there were multiple roles for women during the 1960s besides mothering or not mothering. In the age of professionalism, or incipient careerism, a woman would have been expected to have identities other than her status as a bearer of children. Just as so many of Plath's journal entries dealt with her future work, and the conundrum of which work a talented woman writer, artist, and teacher should take up, so many of her poems deal with the varieties of achieving women. It is also clear in her journals that she was intentionally searching for women writers to emulate. She regularly mentions Virginia Woolf, Emily Dickinson, Stevie Smith, Willa Cather, Lillian Hellman, Louise Bogan, Adrienne Cecile Rich (often with some asperity, since Rich was her contemporary and by having won the Yale Younger Poets competition, already headed toward an important career as poet). [1. Sylvia Plath, Journals, pp. 32, 54-5, 152, 164, 186, 196, 211-12, 217, 310, 316-17, 321.] In fact, Liz Yorke has concluded that the journal entries "make it clear that Plath made a self-conscious decision to study women. Her critique of the ideology of the feminine; her critical consciousness of women's emotional, erotic and economic loyalty and their subservience to men can be shown as developing continuously from this time [1958]." [2. Liz York, Impertinent Voices, Subversive Strategies in Contemporary Women's Poetry, 1991, p. 66.]

Unfortunately, by the time Plath had freed herself from her apprenticeship modes and was writing in what seemed to be her true voice, she was obsessed with rage at what she saw as the betrayal of their life together - and her opportunity to become a good writer - by her husband. It was barely possible to scrape out time to write during these years with two very young children, yet Plath had. She had finished The Bell Jar and "Three Women," she had worked on several short stories that satisfied her, and many, many poems. Writing within a family household was possible, if difficult. But she was accustomed to difficulties. Plath was not so oblivious to how hard maintaining her writing schedule was, however, as to believe she could write effectively if there were no other adult in that household. The years had made her a pragmatist.

Just as we have seen that she created a mythic structure from her comparison of her own fertile womanhood with the barrenness of other more fashionable women, so it seems plausible that she would emblematize the realm of patriarchal power that not only minded babies but accepted poems, scheduled BBC readings, and wrote reviews as a man of a certain type. For the "old boy network" that was determining her fate as a writer, particularly in England where she had no connections except through her still-outsider husband, she had only anger and even contempt. Her quasi-flirtation with Al Alvarez was prompted at least in part by his power both to accept her work and to review it, and there was frequently a sexual element in her dealings with other established literary men on the British scene. In some ways, the fact that Hughes had begun an affair - while enraging on its own terms - also may have been catalytic in freeing her to express her deep-seated anger against the controlling and male-dominated literary world. Again, York sees the male presence in so many of what can also be read as Plath's "strong woman" poems as more indefinite than the figure of a disloyal husband: "Hatred against men begins to fuel the vitriolic stance of many poems." [3. Ibid.]

Two situations illustrate her frustration at being a woman writer in the British literary world. The first is the narrative of her meeting Alvarez in 1960. Lupercal, Hughes's second poem collection, had just appeared. Admiring it greatly, Alvarez phoned and suggested that he and Ted take their infants for a walk, thereby having a chance to talk about poetry. When he arrived at the flat, Alvarez recalled that Mrs. Hughes struck him as "briskly American: bright, clean, competent, like a young woman in a cookery advertisement, friendly and yet rather distant." He pays small attention to her. But as Hughes is getting the baby's carriage out, Plath turns to Alvarez,

"I'm so glad you picked that poem," she said. "It's one of my favorites but no one else seemed to like it."

For a moment I went completely blank; I didn't know what she was talking about.

She noticed and helped me out.

"The one you put in The Observer a year ago. About the factory at night."

"For Christ's sake, Sylvia Plath." It was my turn to gush. "I'm sorry. It was a lovely poem."

"Lovely" wasn't the right word, but what else do you say to a bright young housewife? . . . [4. A. Alvarez, The Savage God, p. 8.]

The apparent inability to equate "housewife" and "young mother" -- not to mention, perhaps, "American" -- with "poet" created little more than a minor social gaffe here, but Plath's life was filled with occasions when she was the quiet American to her husband's ever-growing reputation as one of England's brightest rising stars. At a Faber & Faber cocktail party, she is called out into the hall to witness Hughes's having his picture taken in the company of Stephen Spender, T. S. Eliot, Louis MacNiece, and W. H. Auden. There was no question that Auden would remember having a brief conference with the Smith coed Sylvia Plath, yet now he is standing only six feet from that girl's poet spouse. As the five men look into the camera, sherry glasses in hand, there is an air of self-congratulation that Plath would have found difficult to stomach. [5. See photo in Wagner-Martin, Sylvia Plath, photo section after p. 104.]

As he recounted that first meeting, Alvarez had the conscience to admit, "I was embarrassed not to have known who she was. She seemed embarrassed to have reminded me, and also depressed." [6. Alvarez, Savage God, p. 8.]

- p. 146 [(Part Two)/13 - The Usurpation of Sylvia Plath's Narrative: Hughes's Birthday Letters]: When Plath's Collected Poems won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1982, that award re-established the importance of her writing and helped to cut through the sense of legend that the first publication of Ariel in 1965, two years after her suicide, had initiated. Those Ariel poems, important as they were, were so immediately, so intimately, tied to her death that readers found it difficult to comprehend such poems as "Lady Lazarus," "Daddy," "Words," "Edge" and the others without remembering her end.

The same phenomenon occurred after her novel, The Bell Jar, was published in the States in 1971. (The novel had appeared in England, under the signature of "Victoria Lucas," just a few weeks before Plath's death in 1963 -- to good review and many comparisons with J. D. Salinger's The Catcher in the Rye; it was republished in England under Plath's name in 1966.) The delay of its US publication, however, made it something of a cult book. The Bell Jar, the novel that Plath thought ended happily, with Esther Greenwood's leaving the mental institution to return to college -- recovered, well, herself again -- also gained a last and final chapter in readers' imaginations: Plath's suicide had irrevocably rewritten that happy ending, and readers found the fictional character's recovery to be only a sad whistling in the dark, a keen reminder of the fragility of the human psyche.

- from Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes by Margaret Dickie Uroff; p. 34: If Hughes introduced her to nature, she had made her own investigations into myths when she was at Smith, working on her senior thesis on the double in Dostoevsky.

- from Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems [Edited by Ted Hughes]; pp. 222-224 (Daddy):

Daddy

You do not do, you do not do

Any more, black shoe

In which I have lived like a foot

For thirty years, poor and white,

Barely daring to breathe or Achoo.

Daddy, I have had to kill you.

You died before I had time --

Marble-heavy, a bag full of God,

Ghastly statue with one gray toe

Big as a Frisco seal

And a head in the freakish Atlantic

Where it pours bean grean over blue

In the waters off beautiful Nauset.

I used to pray to recover you.

Ach, du.

In the German tongue, in the Polish town

Scraped flat by the roller

Of wars, wars, wars.

But the name of the town is common.

My Polack friend

Says there are a dozen or two.

So I never could tell where you

Put your foot, your root,

I never could talk to you.

The tongue stuck in my jaw.

It stuck in a barb wire snare.

Ich, ich, ich, ich,

I could hardly speak.

I thought every German was you.

And the language obscene

An engine, an engine

Chuffing me off like a Jew.

A Jew to Dachau, Auschwitz, Belsen.

I began to talk like a Jew.

I think I may well be a Jew.

The snows of the Tyrol, the clear beer of Vienna

Are not very pure or true.

With my gipsy ancestress and my weird luck

And my Taroc pack and my Taroc pack

I may be a bit of a Jew.

I have always been scared of you,

With your Luftwaffe, your gobbledygoo.

And your neat mustache

And your Aryan eye, bright blue.

Panzer-man, panzer-man, O You--

Not God but a swastika

So black no sky could squeak through.

Every woman adores a Fascist,

The boot in the face, the brute

Brute heart of a brute like you.

You stand at the blackboard, daddy

In the picture I have of you,

A cleft in your chin instead of your foot

But no less a devil for that, no not

Any less the black man who

Bit my pretty red heart in two.

I was ten when they buried you.

At twenty I tried to die

And get back, back, back to you.

I thought even the bones would do.

But they pulled me out of the sack,

And they stuck me together with glue.

And then I knew what to do.

I made a model of you,

A man in black with a Meinkampf look

And a love of the rack and the screw.

And I said I do, I do.

So daddy, I'm finally through.

The black telephone's off at the root,

The voices just can't worm through.

If I've killed one man, I've killed two--

The vampire who said he was you

And drank my blood for a year,

Seven years, if you want to know.

Daddy, you can lie back now.

There's a stake in your fat black heart

And the villagers never liked you.

They are dancing and stamping on you.

They always knew it was you.

Daddy, daddy, you bastard, I'm through.

12 October 1962

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

-

-

(as per tcaudilllg)

(as per tcaudilllg) And thank you

And thank you . As for

. As for

too...

too...

--- Poet

--- Poet